A Smashing Display

A space probe slams into a comet and sends up a mighty cloud of dust.

By Emily Sohn

Fireworks thrilled viewers all over the United States on the Fourth of July. An even bigger display took place deep in outer space on the same day.

About 83 million miles from Earth, at 1:52 a.m. Eastern time, a projectile released by a spacecraft called Deep Impact smashed into Comet Tempel 1. In Maryland, Lucy McFadden was watching the event with about 50 coworkers. Even though it was the middle of the night, she didn’t feel sleepy at all.

“We were observing on a big screen, and all of a sudden there was a big, bright flash,” McFadden says. “I was stunned. It was just awesome to see. We were jumping up and down.” McFadden is an astronomer at the University of Maryland, College Park.

|

|

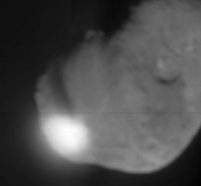

A bright flash marked the spot where a projectile launched by the Deep Impact spacecraft crashed into Comet Tempel 1.

|

| NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD |

The collision was no accident. Scientists first proposed a comet-slamming mission in 1996, and work on Deep Impact began in 2000. Launched in January 2005, the spacecraft was designed to release a probe that would slam into Tempel 1. The spacecraft would also take pictures and make measurements of the collision. The mission’s goal was to see, for the first time, what comets are like on the inside.

Wild orbits

A comet is a ball of ice, dust, and frozen gas that travels around the sun. A typical comet follows an orbit that brings it close to the sun, then swings it far out beyond the outer planets.

Many comets speed by Earth on a regular schedule. Halley’s comet, for instance, visits our neighborhood every 76 years. Other comets have such wild orbits that they may pass us once but never come back.

When a comet nears the center of the solar system, the sun’s heat vaporizes some of its ice, giving the comet a telltale tail.

|

|

Comet Tempel 1, as observed from a telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory, shows a bluish ring of gas around the comet and a pinkish dust jet (pointing toward the lower right corner of the image).

|

| Tony Farnham and Matthew Knight, University of Maryland |

Ancient cultures noticed comets and either feared or admired them. Some people believed that a comet’s appearance foretold the future, hinting at major events to come on Earth.

These days, astronomers are interested in studying comets for the secrets they might hold about how our cosmic neighborhood was created.

“Comets give us a look back in time to the beginning of the solar system,” McFadden says. “They formed long ago and far away at the edge of the solar system, many hundreds of thousands of times farther away from the sun than Earth is.”

There’s even a hypothesis that water and the ingredients for life were first delivered to Earth when comets struck our planet a long time ago. So, learning more about comets could help us learn more about ourselves.

Space balls

Three previous space missions had flown past comets and taken pictures. But these pictures didn’t reveal what the icy space balls are like on the inside.

For years before the launch of Deep Impact, scientists considered a variety of possibilities. Comets could be dense and strong, hard and brittle, light and fluffy, or soft in the middle with a hard crust on the outside.

|

|

Crater expert Peter Schultz and his coworkers at Brown University did experiments to see what might happen to a comet hit by a projectile.

|

| Brown University |

To see how each of these types of objects would behave when pummeled, geologist Peter Schultz of Brown University and his coworkers experimented in the lab, building a variety of miniature models of comets out of sand, ice, and other materials.

In a vacuum to simulate space, the scientists used a giant gun to shoot pellets at the artificial comets from different angles. Some of the models exploded into many bits. In other cases, it looked like a space probe would just bury itself in the comet and stop, with no rebound at all.

So, what would happen when a probe actually struck a comet? If the comet were mostly solid ice, the projectile would probably gouge out a small crater. If its surface were like powdery snow, the projectile could even tunnel right through.

“I was hoping that such an impact would form a big curtain of debris that would be ejected after the shock waves hit the surface,” McFadden says. This was the scenario that looked most spectacular and beautiful in the lab.

Impact

When the space probe crashed into Tempel 1, it produced a bright flash. About a second or so later, there was a second flash, and the comet belched out a fan-shaped plume of debris.

|

|

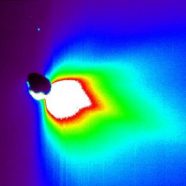

This image, which has been colored to highlight important features, shows the plume of material kicked up by the Deep Impact probe’s impact. The comet itself is silhouetted against the light reflected from surrounding dust. The plume was very bright, suggesting that the comet’s surface material must be very fine, like talcum powder. The image was taken by the Deep Impact spacecraft 50 minutes after the probe’s crash. The blue speck in the upper left corner is a star. |

| NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD |

These observations suggest that the probe ran into fluffy material—very fine dust on the comet’s surface—creating the first flash. The probe then burrowed into the comet and exploded. A high-speed plume of gas blew back out the path created by the probe, creating the second flash. A slower shock wave then reached the surface, releasing a cloud of debris.

By comparing the real explosion to what they had seen in lab experiments, the scientists concluded that Comet Tempel 1 is largely light and fluffy.

“If it were a snowball and you tried to pick it up,” McFadden says, “it would collapse.”

There’s still plenty of analysis left to do. Scientists are now looking through the images frame by frame to peel back the layers of the comet and see how different the inside is from the outside. That might reveal something about how the solar system has evolved over time.

Future mission

Meanwhile, the mission’s work isn’t yet done. Although the probe was destroyed, Deep Impact itself remains in orbit around the sun. It’s currently scheduled to fly past Earth in late December 2007. It may yet get a chance to visit another comet or to set off on some new mission.

|

|

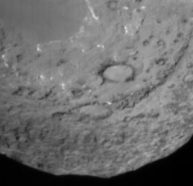

A view of Comet Tempel 1’s surface, as seen from Deep Impact’s probe just 90 seconds before it slammed into the comet.

|

| NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD |

If you’re worried about poor, innocent comets getting smashed to bits, don’t fret, McFadden says. First of all, there are billions of comets out there, and comets get hit in space all the time. Most of them are already pockmarked with craters and other features.

Secondly, comets are not as fragile as you might think. Deep Impact’s probe weighed 820 pounds and was about the size of a washing machine. Tempel 1 is about 9 miles long and 2.5 miles wide, or about half the size of Manhattan.

“It was like a gnat running into a 747 jet,” McFadden says. The comet is still moving along on its original path as if nothing had happened.

Keep your ears open for more comet news. A spacecraft called Stardust is on its way back to Earth from the comet Wild 2, where it collected samples in January 2004. It’s scheduled to deliver its load early in 2006.

And, as scientists continue to look at the data from Deep Impact, more surprises are bound to flare up.

Going Deeper: