Sniffing for cancer

New surgical tool offers surgeons speedier diagnosis of tissues that are cancerous

Meet the iKnife: It’s a new tool that may help surgeons shorten the operating time for cancer patients. Within three seconds, it can tell whether cut tissue is healthy or cancerous, a new study finds. The same identification takes up to 30 minutes when done by a person, as it is now.

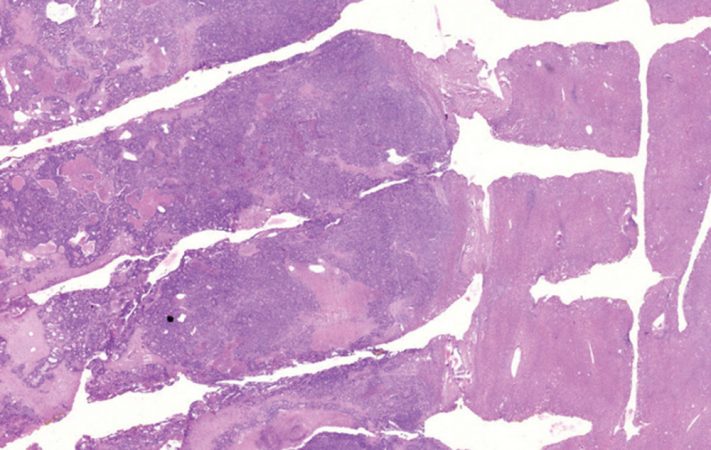

Any diseased cells left behind during cancer surgery can cause a new tumor, allowing the disease to spread. So surgeons face a balancing act. They try to cut out every last bit of diseased tissue, but no more than is absolutely necessary. That can be tricky around the edges of the tumor. That’s where diseased cells join healthy ones.

Surgeons often use electric currents to zap diseased cells, rather than a sharp blade to cut them out. These electric tools are “as common as scalpels,” Zoltán Takáts told Science News. Takáts, a chemist at Imperial College London, led the new study. As it heats tissue, this new type of electric “knife” releases some smoke. It’s ash from the zapped cells. The iKnife analyzes the smoke to tell if the cells had been healthy or diseased. The approach is similar to diagnosing what type of wood a fire had burned by studying the smoke.

With the iKnife, “They are basically blowing up tissue, making smoke out of it and then sampling that smoke,” Nicholas Winograd explains. A chemist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park, he did not work on the new study. “I don’t think it’s at all obvious that this kind of thing would work and I give them a lot of credit for developing it,” he told Science News.

The iKnife “sniffs” the smoke using mass spectrometry (spek TROM eh tree). It’s a standard tool that chemists use to uncover the ingredients in some unknown sample. Spectrometry can detect what types of material were in the ash. For example: Takáts’ team found that healthy cells have different proportions and types of fat than cancerous cells. The iKnife might measure fat particles in smoke to identify which cells — healthy or cancerous — were burned.

The scientists tested the iKnife on 91 patients with cancer. For each patient, the device delivered a diagnosis that matched that given by a pathologist. This type of doctor is trained in examining tissues for evidence of trauma and disease. Takáts’ team reported its findings July 17 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The iKnife is off to a promising start. But before it can be released for use in operating rooms throughout the world, scientists must first test the tool repeatedly in human trials. Researchers must confirm that iKnife analyses are as reliable as the ones today performed by pathologists.

Power Words

mass spectrometry A technique used to determine the chemical makeup of a source material.

tissue Any of the distinct types of material, comprised of cells, which make up animals, plants or fungi.

electric current The flow of electricity along a given path.

cancer The rapid, uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells. It can lead to tumors, pain and death.