A bit of stress may help young people build resilience

A study in monkeys confirms the long-held idea that moderate stress can be good for us

No kid enjoys tough problems, bad news or failure. Yet making it through such stressful situations can help us become more resilient so that we weather the hard times better.

Artem Peretiatko/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Enduring hardship early in life, such as homelessness or losing a parent, is awful. And worse, it can mean a difficult road ahead. A completely stress-free life seems like a much better alternative. But it isn’t necessarily a good thing, research is now showing. A small amount of stress may actually help kids build mental toughness.

“We learn to handle stress by handling stress,” says Megan Gunnar. She works at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. As a developmental psychobiologist (SY-koh-by-OL-uh-gizt), she studies how the body copes with stress. Her work focuses on such effects in children and adolescents.

Feeling crushed by an intense stressor, such as abuse or a parent’s death, can impart a sense of helplessness. That leaves people “fearful of it happening again,” Gunnar explains. A stressful experience shows us that “the world is tough,” she says. “But we can deal with it, perhaps with the help of family and friends,” she adds. And it makes us “tougher the next time.”

Resilience is the ability to bounce back after a bad experience. In one 2010 study, researchers wanted to understand how pain and stress affect resilience. They surveyed 2,398 adults in the United States. Participants answered questions about their mental health and overall well-being. And they indicated if they had experienced varying levels of adversity. This might be a serious illness or divorce in the family.

The upshot: Adults who faced some adversity reported fewer symptoms of psychological distress than did those who had experienced heavy adversity. They also fared better than those who had sailed through childhood with few hard times.

David Lyons is a behavioral neuroscientist at Stanford University in California. His team reported causal evidence for this correlation in a November 2019 paper in Scientific Reports. It would not be ethical to randomly assign humans to experience such stressful conditions. So the team studied squirrel monkeys that had not yet reached puberty. These monkeys experienced varying “doses” of stress.

“No-stress” monkeys enjoyed a typical life in the lab. They were housed in a cage with their mother and siblings. There was plenty of water and food. They also got toys. A second group faced a mild stressor. They spent an hour a day away from their siblings on 10 straight days. The stress dose went up a notch for a third group. These monkeys had daily separation from siblings and no access to mom during that hour. Two more groups experienced daily separation from both their mother and siblings. They also received an injection as yet one more stressor.

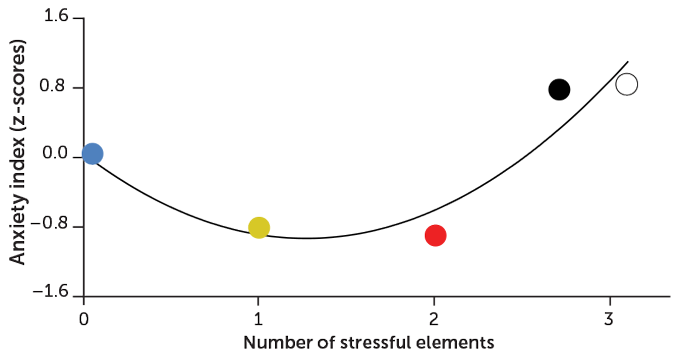

Early-life stress affects later resilience

Ten weeks later, each monkey was moved with its mother to an unfamiliar cage. The researchers assessed the monkeys’ willingness to let go of mom and explore the new digs. The team also analyzed levels of the stress hormone cortisol in the animals’ blood. That blood had been collected before, during and after their time in the new cage.

On the whole, monkeys that faced one or two stressors (groups 2 and 3) clung less to their mothers than those in the last two groups. They also more readily explored their new surroundings. In general, they showed less anxiety than both the no-stress and high-stress groups.

The monkeys’ cortisol patterns also reflected this trend. Animals that were exposed to mild-to-moderate stress toned down their cortisol spikes more quickly than the other groups.

Growing up healthy means “learning how to deal with mild challenge and change,” Lyons concludes.

This story was produced with support from the D.H. Chen Foundation.