Some young adults will volunteer to get COVID-19 for science

This human challenge hopes to learn how much coronavirus it takes to sicken us

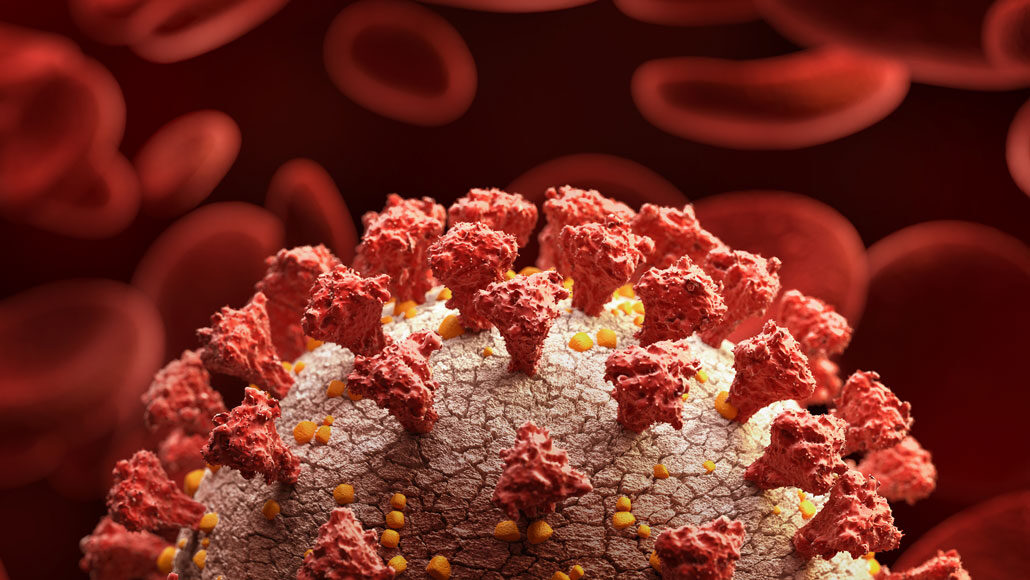

In the first approved human-challenge trial for COVID-19, researchers will intentionally expose volunteers to the coronavirus (illustrated) to determine how little of the virus is needed to cause infection.

Radoslav Zilinsky/Moment/Getty Images

Within a few weeks, researchers will deliberately expose dozens of healthy young volunteers to the new coronavirus. This trial, which will take place in the United Kingdom, will be the world’s first COVID-19 human challenge.

The U.K. government approved it on February 17 after a review of the trial’s design and ethics. This research seeks to learn how much virus is required to kick-start an infection. Later, researchers might address other questions, such as how well different vaccines work against the virus.

In challenge trials, people volunteer to be infected with a germ. Afterward, researchers closely study the progression of disease in these people or how they respond to potential treatments.

Only in such trials can researchers know precisely when people were infected and with how much virus. Such data offer a level of detail unavailable until now. Normally, researchers must watch and wait for participants to pick up the disease on their own. Seldom could they know precisely when that exposure took place nor how big it was.

The idea of challenge trials for COVID-19 has stirred controversy. Some experts question whether it’s fair to put healthy people at risk when questions remain about the long-term effects of this virus. Here, however, U.K regulators argued that the promise of speeding up research findings outweighed the risks to young adults. Such young adults face a lower risk of severe impacts than do older people. Still, some young adults have developed serious illness — even died.

“I think a case could be made that the risks are acceptable for young, healthy volunteers,” says Seema Shah. She works at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago, Ill. She was not involved in the trial. But as a bioethicist, she is used to studying how research in biology and medicine can be done fairly and in ways that pose the fewest risks to participants.

Volunteers will be watched closely

Researchers hope to enroll up to 90 healthy volunteers. To take part, none can have been infected with this coronavirus before. All must be between 18 and 30 years old. They will be exposed to varying levels of the virus. Researchers will use the virus type that’s been around since March 2020. The recruits will then remain in isolated hospital rooms for some time. Medical professionals will monitor them day and night.

Andrew Catchpole is chief scientific officer at hVIVO. It’s a group in London, England that will help run the trial. In a news statement, he says this 24/7 monitoring of volunteers will allow the researchers to learn how small a dose is needed to start an infection. Since the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, this has been a big question. Researchers also will be able to track how each person’s immune system responds to their infection.

Such questions are important, says Shah. But, she adds, there also is some question of how much impact this trial will have. After all, other coronavirus variants have evolved that are more contagious, and perhaps more deadly. They are now starting to become the most common types. If they behave differently than the strain used for this trial, knowledge gained from the new research may not fully apply to most future cases of COVID-19.

For example, Shah notes, “If you’re doing a challenge trial with a strain that is eventually no longer the dominant strain, what does that tell you about vaccine efficacy?”

So far, researchers have not shared details with the public of how this coming human challenge will work. But they plan to do so soon.