Spacecraft need an extra boost to travel between stars

Experts ponder how future technology might take us to the cosmos

In Star Wars, spacecraft move faster than the speed of light. In reality, reaching light speed would require an infinite supply of energy.

YUKHYM TURKIN, SHUTTERSTOCK; PIXELSQUID/SHUTTERSTOCK

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

In Star Wars, pilots enter a dimension — hyperspace — to travel between different worlds. To merge onto this cosmic highway, the ships are equipped with special engines called hyperdrives. Once inside hyperspace, these speedsters zoom faster than light. With a push of a lever, the spacecraft can travel between star systems in a few hours to days.

Science fiction makes space travel look easy. But many of these stories break the laws of physics to get from planet to planet. Off-screen, the technology needed to reach another star system doesn’t yet exist. However, emerging propulsion methods could brighten the future of interstellar travel.

To infinity and beyond

Astronomers measure space using light-years, or the distance light travels in one year. Light speeds through interstellar space at around 300,000 kilometers (186,000 miles) per second. Proxima Centauri, the nearest non-sun star to Earth, is 4.24 light-years away.

Using something like hyperdrive to travel between star systems would be impossible, says Scott Bailey. An engineer at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Bailey designs instruments to study Earth’s atmosphere. “That’s like driving [a] car right to the mall that’s light-years away,” says Bailey. “That’s not going to happen with any sort of propulsion.”

Even reaching light speed is impossible. That’s because, due to the nature of light and energy, it would take an infinite amount of energy to reach that speed, says Bailey.

The fastest any humanmade object has traveled is only about 0.05 percent of the speed of light. At this speed, it would take about 7,700 years to reach the exoplanet Proxima Centauri b.

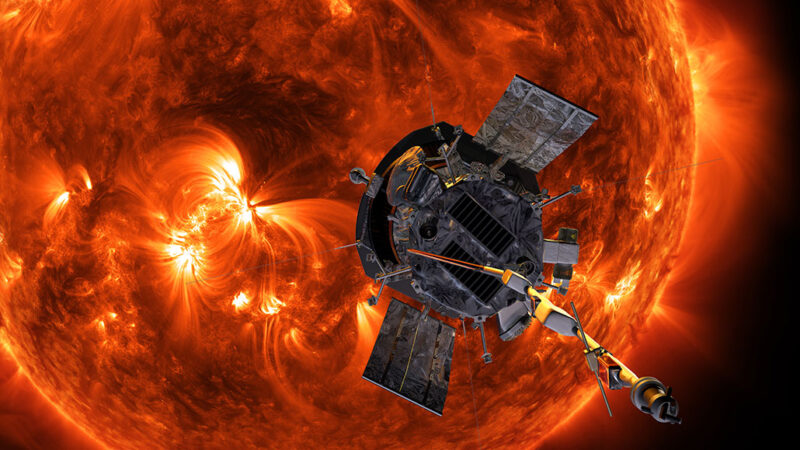

A spacecraft traveling at a tenth of the speed of light could shave down the trip to Proxima Centauri b to a quick 40 years. Future engineers could use nuclear power to achieve such a speed, says Bailey, but developing that technology could take thousands of years.

Controlled fusion could help, says Cole Miller. Miller is an astronomer at the University of Maryland, College Park. Controlled fusion harnesses energy from combining atomic nuclei to create a steady supply of power. Researchers have been working on controlled fusion for about 70 years. But these experiments have yet to produce more energy than they consume, Miller notes.

Sail away

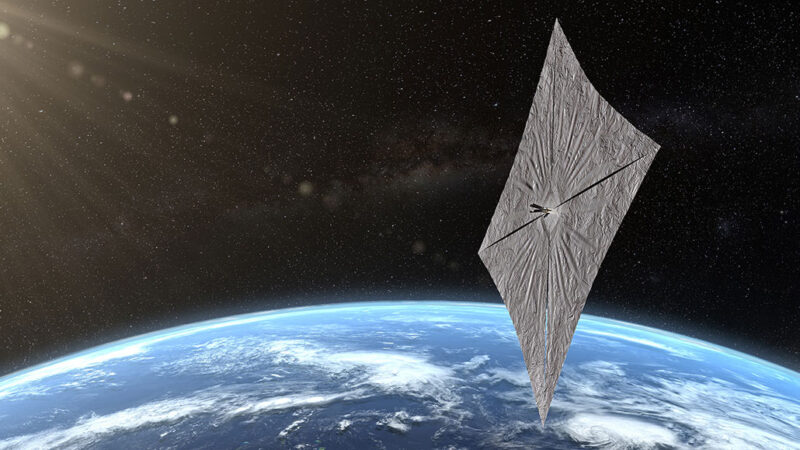

Some vehicles in the Star Wars universe rely on “sun jamming” to zip along using solar wind. This “wind” is the constant stream of charged particles produced by stars. These spacecraft have huge sails that catch the solar wind, moving through space like a ship on the sea.

The Planetary Society crowdfunded a small spacecraft, Lightsail 2, that moved in a similar way. Rather than relying on solar wind, though, these solar sails used pressure from sunlight itself.

Although light doesn’t have mass, it does have momentum. Solar sails intercept sunlight with thin sheets made of polymers and a reflective plastic called Mylar. When speeding photons hit the sail, they bounce off and transfer energy. These small and repeating collisions create a force that can push objects along.

Lightsail 2 launched in 2019 and orbited Earth for about three years before reentering the atmosphere.

But using solar sails to propel a large spacecraft would be tough, says Miller. The thrust produced probably wouldn’t be strong enough to carry large ships ferrying humans.

Upscaling solar sails would offer unique benefits, however. Using sunlight would allow a spaceship to accelerate without fuel. And unlike Earthbound objects, spacecraft aren’t slowed down by air friction produced by an atmosphere. This would allow any spacecraft to continue gaining speed as long as it’s exposed to sunlight.

Finding the force

Star Wars makes the cosmos seem like a raceway. But the immense distances separating worlds hinder space travel, even within our solar system.

For now, the longest distance we’re looking to transport people is to Mars, says Jarred Young. This engineer studies propulsion systems at the University of Maryland, College Park. Researchers are eyeing new methods that could bring people to and from the Red Planet safely, he says.

One of these is ion engines. These thrusters create force by shooting charged atoms from the back of a spacecraft. Star Wars’ TIE Fighters wind through space battles with them. But real ion engines work best with straight paths, says Young. “It’s essentially point-and-click propulsion.”

Ion engines aren’t as powerful as the chemical propellants used in rockets. Chemical rockets create thrust by combusting fuel and oxygen-releasing substances called oxidizers.

But chemical rockets only burn for a short time. Ion engines can last months or even years, possibly helping fuel future trips to Mars. These thrusters, though, aren’t yet strong enough to propel massive spacecraft that far, Young says.

And for now, reaching new worlds is only possible in fictional galaxies far, far away.