Speedy sharkskin

Tiny, toothlike bumps boost sharks’ swiftness

The shortfin mako shark is one of the fastest fish in the sea. It slices through the water at speeds exceeding 45 miles per hour (72 kilometers per hour). A team of Harvard biologists has made a surprising discovery about what gives this, and all other sharks, their incredible swiftness: It’s their sandpapery skin.

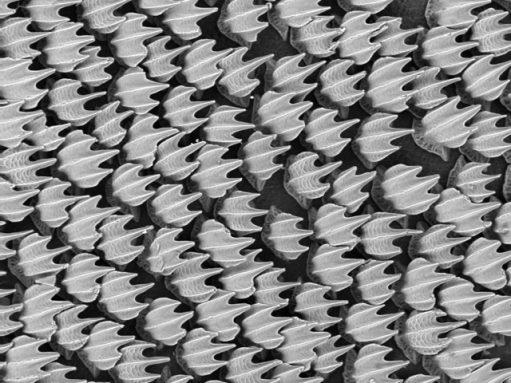

It may look sleek and smooth, but a shark’s skin is actually rough. Millions of microscopic, toothlike bumps called denticles cover the skin. Scientists have long recognized that denticles help reduce drag. Drag is a force in the direction opposite to an animal’s movement. Drag slows an animal down.

Water is hundreds of times denser than air. And this, in part, explains the greater drag that things moving through water experience compared to objects moving through air. You can experience this difference by waving your hand in the air, and then waving your hand in a tub full of water. Denticles help minimize drag by changing the way water flows over a shark’s body.

But the new study by Johannes Oeffner and George V. Lauder shows that the rough surface of sharkskin also increases thrust. Thrust is a force in the direction an animal is moving. And this thrust helps swimming and flying animals overcome drag.

“Sharkskin denticles seem to provide a clever boost,” explains Lauder. This increase in thrust due to skin may help push sharks even more quickly through the water, he and Oeffner say.

Their experiments show that denticles generate tiny swirls around a shark’s body as it moves. This creates a small suction effect — the thrust — that helps drive the fish’s body forward.

Importantly, the Harvard team’s tests investigated how sharkskin performs when attached to a stiff plate, as well as when attached to a piece of flexible material. The flexible material mimics the actual motion of a swimming shark’s skin — and its millions of denticles. It was only when studying the flexible sharkskin that the scientists discovered the role denticles play in generating thrust.

Denticles have other helpful properties, too. Unlike whales, sea turtles and many other large animals that live in the ocean, sharks rarely have barnacles, algae or other sea creatures attached to and living on their skin. How do sharks stay so clean?

Scientists suggest that at the microscopic level, denticles make the surface of sharkskin too rough and uneven for other organisms to attach. It’s a property some medical-device manufacturers have adopted: Medical equipment with a sharkskin-like surface slows or stops bacterial growth. And that could help reduce the spread of bacterial infections. That’s an important factor in settings like hospitals and doctors’ offices.

Sharkskin-like coatings also help to keep boats free of marine algae and other clingy organisms.

But one thing sharkskin-inspired materials probably don’t do is improve the speed of a human swimmer. In their experiments, the scientists found that sharkskin-like features woven into the high-tech suits worn by competitive swimmers offer the fabric no performance advantage. It means that other aspects of the suits, such as the compression they provide, probably explain their performance.

Power words (Adapted from the American Heritage Children’s Science Dictionary):

Denticles: Microscopic, toothlike scales covering the bodies of sharks and rays.

Drag: A force opposite to an object’s motion; it slows the motion of the object.

Thrust: A force that makes an object move forward.