From stem cell to any cell

The search is on for ways to use stem cells to treat injuries and cure diseases.

By Emily Sohn

For maybe a day, about 9 months before you were born, you were just one cell. Then you were two identical cells. Then you were four. Then eight.

Since then, you’ve grown into a complicated organism with many trillions of cells grouped into specialized tissues and organs. The cells in your brain do the thinking. The cells in your heart pump blood. The cells in your tongue let you taste food. And so on.

In recent years, scientists have made an amazing discovery. Even though most cells have specific jobs, some primitive cells — called stem cells — exist in everyone’s body. Stem cells are unspecialized cells that can develop into nearly any type of body cell.

|

|

These images show human embryonic stem cell colonies, as grown in 1998 by researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in different stages of development.

|

| © Science |

Embryos — babies in the earliest stages of growth before they are born — have stem cells. Certain tissues in adults also contain stem cells, although the range of cells into which they can develop is limited.

In 1998, scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison figured out how to collect human embryonic stem cells and make them grow. Since then, researchers have learned to mix stem cells with combinations of proteins called growth factors to make the cells grow into different types of cells. Now, the search is on for ways to use stem cells to treat injuries and cure diseases.

For example, stem cells could be extracted, turned into new bone cells, and then injected into weak or broken bones. Or, they could become nerve cells that could heal spinal cord injuries, skin cells that could replace badly burnt skin, or brain cells that could help people who have suffered brain damage. The possibilities are endless.

“At this point, the ability to create all the different cells in the body has been pretty much proven to be real,” says Gary Friedman. He’s director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine in Morristown, N.J. “All the focus now is on getting new cells to behave the way we want them to and to go where we want them to go.”

Living better

Treating heart disease is one promising area of research. In dishes in the laboratory, scientists have already turned stem cells into heart cells, which gather into a group and throb in synch with one another, just like cells do in your heart.

At the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, researchers are now taking stem cells from a patient’s own body and injecting them into the heart to rebuild heart tissue and combat heart disease.

|

|

Human embryonic stem cells can turn into a variety of different cell types, including (A) gut, (B) neural cells, (C) bone marrow cells, (D) cartilage, (E) muscle, and (F) kidney cells.

|

| © Science |

Elsewhere, scientists are working to battle spinal cord injuries, diabetes, cancer, and more. But stem cells can’t cure all our ills. Some health problems are proving harder to treat this way than others.

Hearts, nerves, and livers are simple, Friedman says. Kidneys and lungs, on the other hand, are organs are tougher to repair. In kidneys, for example, stem cells have to not only specialize but also move into appropriate positions.

The goal of stem cell research is to help people live better, Friedman says.

“If kids are looking at their grandparents, maybe they see somebody who can’t walk well or somebody who is partly paralyzed because of a stroke,” he says.

“If you could take an older person and give that person cells to regenerate heart muscle or part of the brain that died during a stroke, or inject cells into joints to take away arthritis, all of a sudden you’re going to have a pretty vibrant person there,” Friedman says.

“This will help society,” he says. “People will be more functional instead of being in a weakened state and having to be cared for.”

More than science

As promising as the research may seem, discussions about stem cells often involve more than just science. Ethics is also involved, along with politics and religion, especially when it comes to stem cells taken from embryos.

So far, embryonic stem cells appear to be more useful than stem cells that come from adults. Because an embryo’s cells are still dividing and specializing anyway, its stem cells can still become almost anything. By the time we grow up, however, our stem cells have a more limited ability to diversify.

|

|

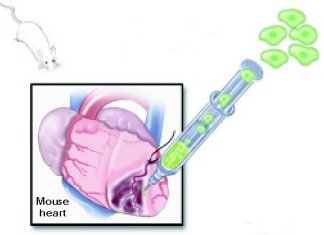

To repair heart muscle in a mouse, researchers inject adult stem cells into the muscle of the damaged wall of a mouse heart.

|

| National Institutes of Health |

The problem with embryonic stem cells, for some people, is that they originally come from destroyed embryos. Many scientists argue that stem cells are our best hope for curing a huge number of diseases. They also argue that fertility clinics end up with a surplus of embryos that are never born anyway.

Nevertheless, critics think its wrong to use cells from dead embryos. It’s a very complicated issue that involves basic beliefs about when life begins, and these are the types of beliefs about which people tend to feel passionate.

Some recent research may help put an end to the debate, Friedman says.

A new technique called “somatic cell nuclear transfer” has given scientists the ability to create embryonic-like stem cells out of a person’s own cells. This strategy is especially appealing to doctors, because it’s always better to use a person’s own cells for transplants and injections. Our bodies often reject cells that come from someone else, even if that someone else is an unborn embryo.

Scientists have also found embryonic-like stem cells in umbilical cord blood. About 100 million babies are born each year, and every one of them has an umbilical cord that connects it to its mother. If umbilical cords prove to be a reliable source, the supply of stem cells could be enormous and controversy-free.

All this may sound a bit confusing, but it’s worth learning more. Stem cells are big news in medicine right now. “I don’t think a day goes by when there aren’t articles or something on the Web about it,” Friedman says.

As you get older, you’re bound to hear more and more about stem cells.

Going Deeper: