Exoplanet hunting, HIV-fighting and math garner big prizes for teens

Forty finalists competed for more than $2 million in awards at the 2019 Regeneron Science Talent Search

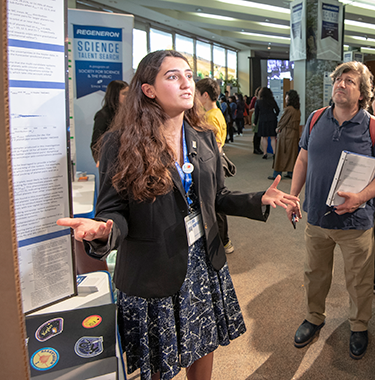

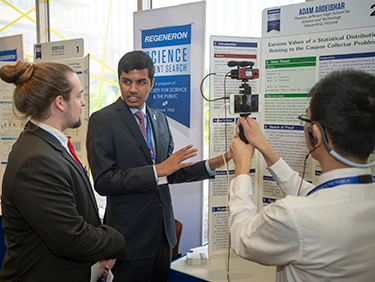

Ana Humphrey (center), Samuel Weismann (left) and Adam Ardeishar (right) took home first, second and third place in the 2019 Regeneron Science Talent Search.

C. Ayers/SSP

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Unsolved mysteries fascinate many of us. It’s why we watch crime shows and read mystery novels. Scientists get fascinated by unsolved mysteries, too. The top three winners in the 2019 Regeneron Science Talent Search all took on their own unsolved mysteries. One hunted for planets in other solar systems that may have snuck past big telescopes. Another uncovered hiding places where HIV — the virus that causes AIDS — likes to lurk. A third, frustrated by an “unsatisfying” answer, tackled a complicated math problem.

Ana Humphrey, 18, took home $250,000 and first prize. Samuel Weissman, 17, won second place and $175,000. Adam Ardeishar, 17, came in third, winning $150,000.

“Looking at today’s finalists and thinking about the students to come, I know we are in good hands,” says Maya Ajmera. “I am thrilled that, together with Regeneron, we are able to continue this competition, now in its 78th year, and provide these young people with a platform to showcase their science.” Ajmera is president and chief executive officer of Society for Science and the Public. This organization created the Science Talent Search in 1942 and still runs the competition. (The nonprofit society also publishes Science News and Science News for Students.)

Each year, the Science Talent Search brings together 40 students from across the United States. They show their science projects to the public and face a panel of judges as they compete for more than $2 million in prizes. The Science Talent Search is sponsored by Regeneron, a company that develops medicines for diseases such as cancer.

Spacing out

Ana Humphrey has always been fascinated by exoplanets — planets in other solar systems. But it’s not because her head is in the stars. Humphrey is a senior at T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria, Va. She wants to learn more about exoplanets so she can answer questions about how our own system formed.

“The only difference between an exo-solar system and our solar system is that we live in ours,” she says. By learning about exoplanets, where they are and how they form, Ana hopes to “learn about how we got here, and why our solar system is the way it is.”

Many scientists who scout for exoplanets look for transits. This is when a planet or moon passes in front of its star. If scientists have a telescope pointed in the right direction, they might see the star’s light dim a little as the planet subtly dims the star’s light.

But not all planets can be detected this way. Some small planets — those the size of Earth, for example — are too tiny. They don’t darken the starlight enough to be detected by today’s telescopes.

Ana decided to hunt for some of these sneaky planets by building a computer program based on the so-called “packed system” hypothesis. This is the idea that solar systems should have as many planets as they can hold — but that they can’t hold too many.

The teen worked with NASA’s exoplanet archive, operated by the California Institute of Technology . This is a free online database of exoplanet information. Ana’s computer program hunted for “unpacked” systems. Finding one meant there might be enough space to support more exoplanets. Ana ended up identifying 560 locations in our Milky Way that might host planets. Of those, 96 were prime targets. She says that means they have enough space between known planets to fit another. To date, none of those “others” has yet been found.

Ana was eager to make sure that she was on the right research track. She ended up getting help from Elisa Quintana. She is an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. The student also talked with Mark Otto, who studies statistics for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Adelphi, Md. “I tried to reach out to as many people as possible to get feedback,” Ana explains.

Viruses undercover

Sam Weissman is a senior at Harriton High School in Merion Station, Pa. Several years ago, he went to Una O’Doherty’s house for dinner with his brother, he had just learned about HIV in school. He knew that O’Doherty studied HIV at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. So he asked about her work. Afterward, he says, “She invited me to spend a week in her lab.”

At the time, Sam was still in middle school, so wasn’t allowed to do more than watch. “I made a lot of coffee,” he recalls. But when he reached high school, the scientist allowed him to start real lab work. Sam wanted to tackle the mystery of how HIV could survive in someone’s body, even after they were treated with drugs to kill the virus.

HIV reproduces in two ways. An infected cell can spit out new HIV viruses that then burrow into healthy cells. And when an infected cell divides, HIV gets another opportunity to spread. It replicates itself inside the dividing cell. “The human cell divides and takes HIV with it,” Sam explains. That keeps HIV in the body and under the radar of the immune system.

Sam and other members of O’Doherty’s lab published their discovery February 13 in the journal Nature Communications.

Unsatisfying answers

Adam Ardeishar came across his Science Talent Search project at … another competition. A senior at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria, Va., he was competing in the Harvard-MIT Math Tournament early last year. As part of that competition, he was asked to solve something called the “coupon collector’s problem.”

Imagine you have a big jar of jelly beans. It’s a mix of 14 different colors. There may be more green ones than pink, and more red than any other color. If you put on a blindfold and drew one bean from the jar at a time, how many jelly beans would you have to pluck out before you’d drawn one of every color? That is the question behind the coupon collector’s problem.

No one has yet solved this problem for every possible number and combination. But in that 2018 competition, Adam gave it a try. “They asked me to estimate the answer,” he says. “But the solution was not very satisfying and not very mathematical.”

Adam couldn’t live with that. “When you’re solving a math problem,” he explains, “it’s like a puzzle. You get the rush at the end when you’re solved the problem.” However, he notes, “When you get an unsatisfying solution, there’s not the same rush.”

The teen decided to take on the coupon collector’s problem himself. He got in touch with a friend, Franklyn Wang. Wang is now a college student at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. But while a senior in high school, Wang also was a Science Talent Search finalist. “He gave me some reading materials,” Adam says. Later, they video chatted while Adam worked out the coupon collector’s problem.

While Adam didn’t completely solve the problem, he came very close. The results could help people better calculate things like extreme events, he says — such as 1,000-year floods or when a bridge might collapse.

“Great scientists … like the 40 young scientists we are honoring here today, are among the most powerful people on Earth,” says Leonard Schleifer. He is the founder and chief executive of Regeneron. “In fact, I consider them as having a super power … the amazing power of traveling to the future and bringing important inventions and discoveries back to the present.” By performing research, he says, these teens “have the power … to change our lives today.”