Study finds big drop in animal populations since 1970

Good news: Most of the studied mammal, bird and reptile populations were stable or up

A chameleon found by the roadside in Kenya. Global populations of vertebrates, including some reptiles, have declined over the past five decades.

WWF

Many wildlife populations around the world are falling in size. The speed and scale of these losses have scientists worried. In less than 50 years, vertebrates — animals such as rhinos, frogs and anteaters — have decreased by about two-thirds. That’s the finding of a new report.

Measuring the size of these populations can be hard. Yet ecologists need such numbers to know how the diversity of Earth’s species has been changing. It also can help them understand how people may be impacting the number and variety of animals.

A group of scientists recently set out to get those numbers. To do that, they worked with the World Wildlife Fund, or WWF, based in Switzerland, and the Zoological Society of London in England. The team studied more than 38,000 populations of animals. These included more than 5,000 species. The new analysis focused on vertebrates (mammals, reptiles, fish, birds and amphibians). It looked for changes in the population size of all groups between 1970 and 2018.

Overall, the study turned up an average drop in population size of 69 percent. The team published its findings in October. Its numbers were part of WWF’s Living Planet Report.

“It gives us a heads up that we need to do something about declining populations around the globe,” says Rebecca Shaw. She’s chief scientist at the WWF’s office in New York City.

Gathering data

As conservation groups, WWF and the Zoological Society of London work to protect animals and nature. Every two years they issue a Living Planet Report on the impacts that people are having on wildlife and biodiversity. Earth’s ecosystems supply us with things like food, clean air and water. Biodiversity is important to the health of those ecosystems, notes Shaw.

Researchers all over the globe collected data on animal populations. They studied how the size of each population changed over time. Computer models then helped them condense this mountain of data into a single number. Called an index, it’s a measure of change.

Animal populations decline before a species goes extinct, notes Brian McGill. He did not take part in the new report. But he’s a biologist at the University of Maine in Orono. “Looking at changes in population size can show us species that are trending toward extinction,” he explains. The species in this study haven’t gone extinct — at least, not yet. So “there is still time for humans to take action and turn things around,” says McGill.

McGill points to the California condor. It’s North America’s biggest bird. It’s also an example of how people can slow or stop a steep decline from turning into an extinction. These birds nearly went extinct due to lead poisoning, hunting and habitat loss. By the 1980s, there were fewer than two dozen condors alive. Wildlife officials captured them all. Then they bred them in the lab and released the offspring when they got old enough. Today, more than 300 California condors soar in the wild.

Finding a trend

The new Living Planet index calculated an average decline of more than two-thirds in populations across the species it studied. But there’s a lot of complexity behind that number, the researchers say.

Among mammals, reptiles and birds, for instance, the abundances of just over half of them increased or held steady. According to the WWF, for instance, wild mountain gorillas increased by almost 70 percent: They went from about 620 individuals in 1989 to just over 1,000 today. Shrinking animal populations saw bigger changes, on average, than did increasing ones. This is why the report calculated an average decline when it viewed all groups together, Shaw explains. Freshwater-fish populations across the globe, for instance, declined by an average of 83 percent.

The report links declining populations to humans and their actions. These include a loss of animal habitats (where wildlands were converted to roads, homes and factories, for instance). This also includes the excess harvesting of certain species and introductions of invasive species. Pollution and climate change also have played a role.

The index doesn’t say how many individuals or species disappeared. And it focuses on vertebrates, of which there are some 45,000 species. They make up only a small share of the estimated 8.7 million species on our planet.

“We can’t assume that patterns found for vertebrates translate to insects or plants or bacteria,” says biologist Brian Leung. He works at McGill University in Quebec, Canada, and did not take part in the new study. Factors such as climate change or habitat loss could drive declines across all species in an ecosystem, Leung explains. “But we can’t know that for sure without studying it.”

Weighing successes and failures

Leung sees a lot of potential in the large amounts of data used to make the Living Planet index. With it, he says, scientists now can begin to look at what might underlie certain patterns in losses.

Yet not all scientists agree on the best way to measure biodiversity. How best to describe those data to the public is another issue. “As a scientist, I see a lot of complexity,” says McGill.

He asks, for instance: “Should we try to take all of that complexity and boil it down to one number?” A single number is easy for people to remember, McGill admits. On the other hand, he worries that hearing bad news about the planet — without understanding the complexity behind it — might make some people feel hopeless. He sees some of his students panicking over what’s happening to the environment. “Big, sweeping numbers can feed into this anxiety,” he says. This might not be helpful, he worries.

In reports on the environment, McGill notes, failures right now seem to outnumber the successes. “Yet the success stories show us that it’s in our power to change things,” he adds. “Let’s tip the balance to having more successes than failures.”

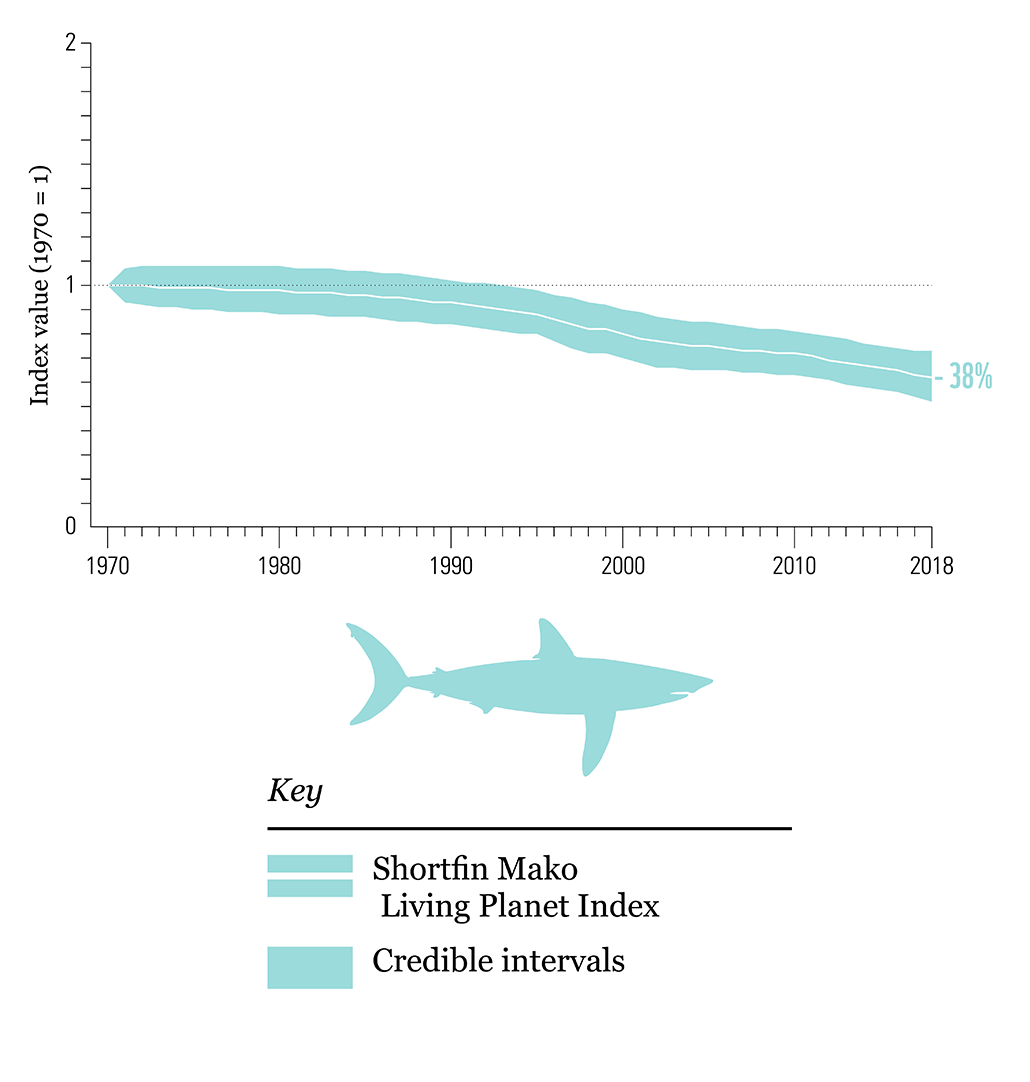

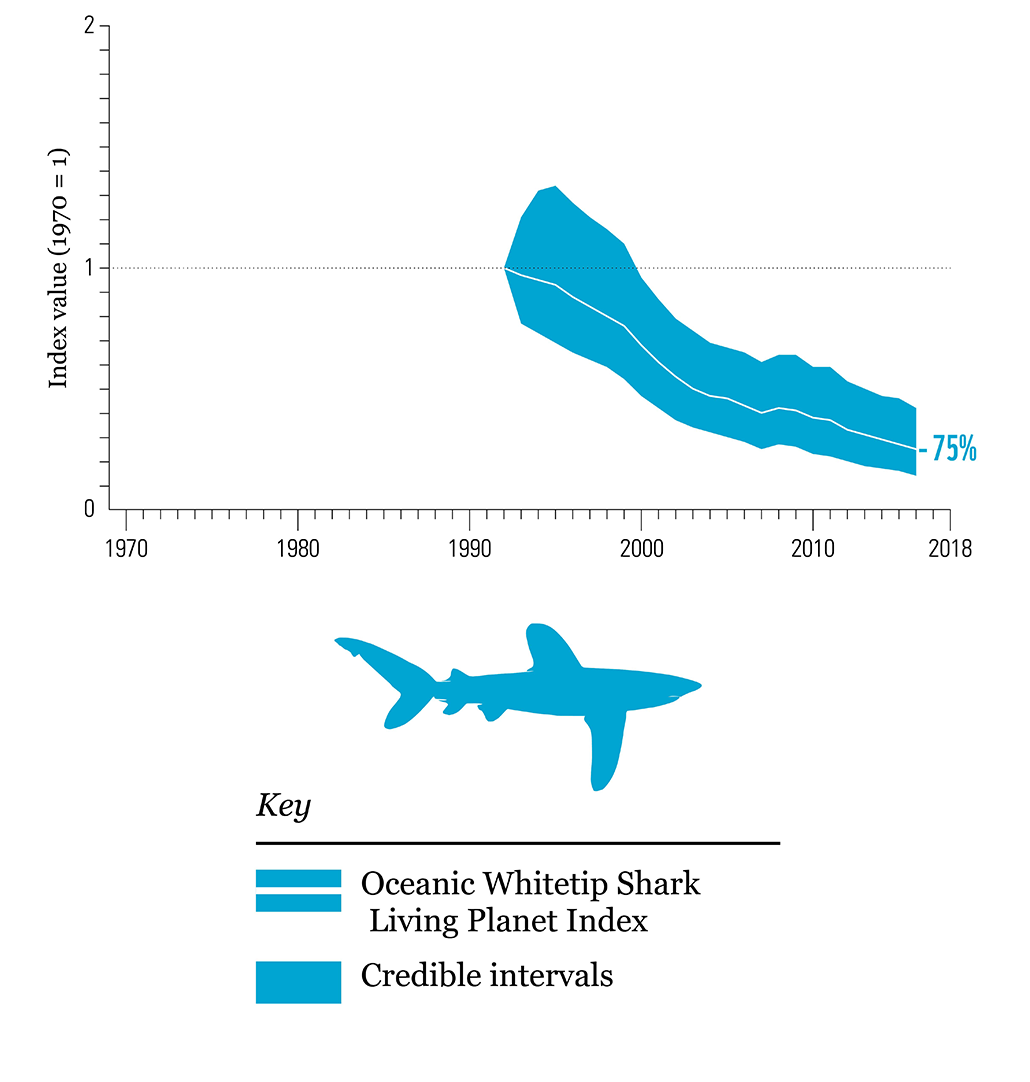

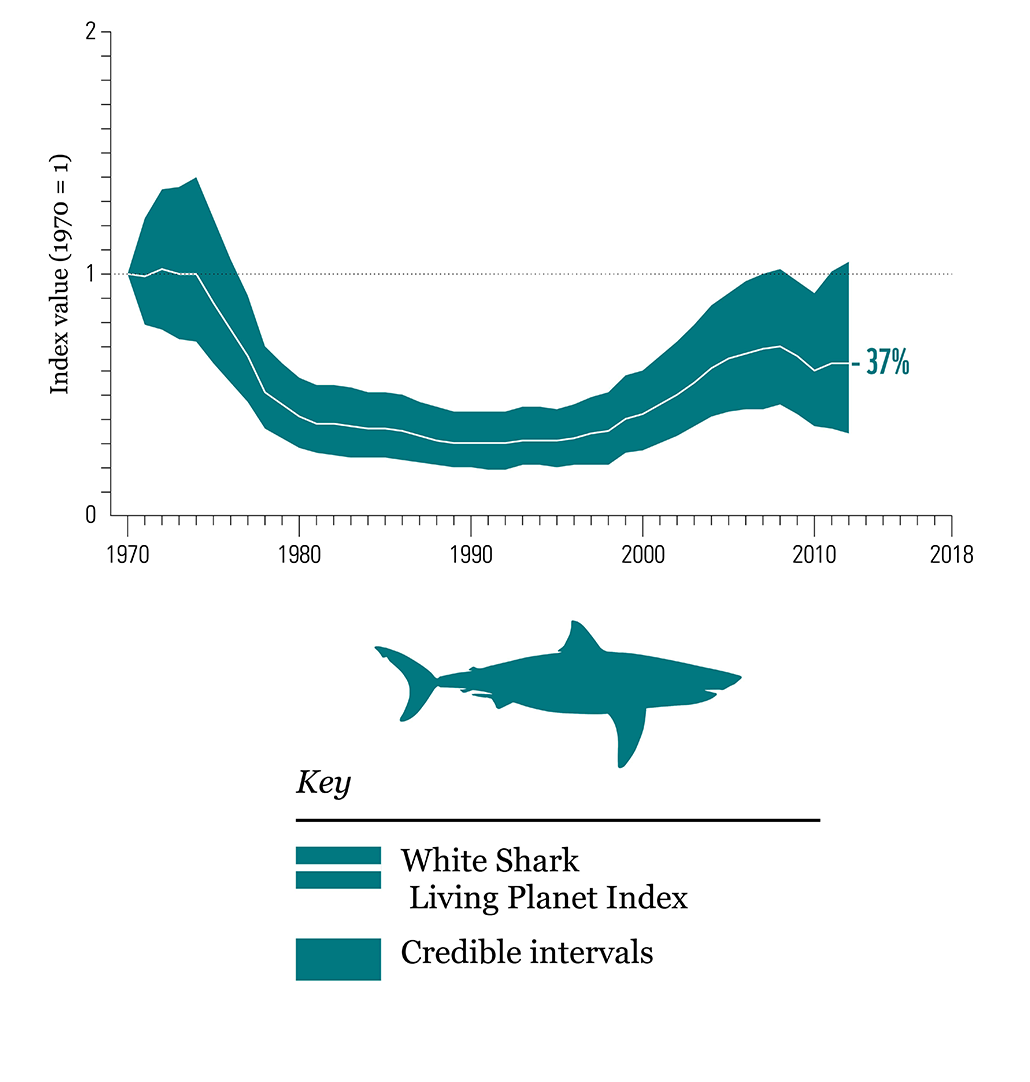

Sharks in peril

These three shark species were formerly abundant in our oceans. Over the past five decades, however, their populations have declined steeply. Fortunately, the white shark is now recovering off both U.S. coasts due to bans on fishing for many shark species.