Study claims to have found oldest human fossils

They seem to expand the time our species is known to have been around by some 100,000 years

Fossils unearthed in Morocco from around 300,000-years ago, including this lower jaw, come from the oldest known Homo sapiens. Or that’s what some researchers now argue. Other scientists suspect the remains come from an earlier, related species.

J.-J. HUBLIN/MPI-EVA, LEIPZIG

By Bruce Bower

In a surprising and controversial twist, the earliest known remains of our species have turned up in northwest Africa, scientists report.

Fossils of Homo sapiens have been unearthed together with stone tools at Jebel Irhoud, Morocco. They date to some 300,000 years ago, an international team of scientists say. They offered their conclusions June 7 in two papers in Nature.

Until now, the oldest human fossils came from much further south, in East Africa. Moreover, they dated to only around 195,000 years ago. That doesn’t rule out humans having evolved in East Africa. But puzzling fossils have turned up elsewhere, too. Some researchers claimed to have unearthed a H. sapiens skull in South Africa. It has been tentatively dated to about 260,000 years ago.

Humankind’s emergence involved populations across much of Africa, the Morocco fossils now suggest. And if the new fossils are truly from H. sapiens, then our species may have been around some 100,000 years longer than previously thought. That’s the conclusion of Jean-Jacques Hublin. He’s a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Hublin led the new Morocco research along with Abdelouahed Ben-Ncer. He comes from the National Institute of Archaeology and Heritage Sciences in Rabat, Morocco.

“Long before the out-of-Africa dispersal of Homo sapiens [70,000 to 60,000 years ago], there was a dispersal within Africa,” Hublin now argues. What’s now the Sahara desert had been inhabitable roughly 300,000 years ago. So early humans in North Africa could have spread to other parts of the continent. There, they could have interacted with different H. sapiens groups, he suspects.

Excavations at Jebel Irhoud in the 1960s turned up six fossils of folk who belonged to species in the Homo genus. Initially these remains had been classified as Neandertals. Stone tools at the site did resemble those at European Neandertal sites. Initial dating suggested the fossils came from about 40,000 years ago. Later, in 2007, a report estimated one fossil from this site, a child’s jaw, was roughly 160,000 years old.

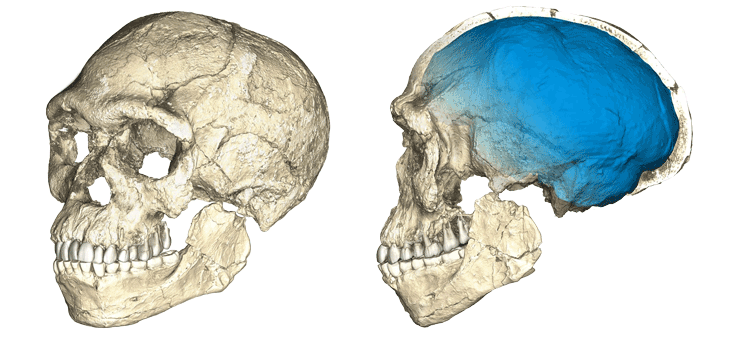

In one of the new papers, Hublin’s group describe 16 newer fossils from Jebel Irhoud. They had been discovered between 2004 and 2011. They included remains of at least five different individuals. Three of them had been adults, one had been a teen and the last a child. The fossils included a partial skull, a lower jaw, a partial upper jaw, six isolated teeth and several limb bones.

The researchers scanned some of the bones with X-rays, using a technology known as computerized axial tomography. From these scans, the scientists generated 3-D reconstructions of the fossil skull and lower jaw. Hublin’s team compared these bones to those from Neandertals, from Homo erectus and from other Homo species. All of these comparison fossils came from between around 1.8 million and 150,000 years ago. The scientists also included, for comparison, true human fossils that were 130,000 years old or less.

Story continues below image.

Facial traits of the Jebel Irhoud skull and teeth were larger than those of people today. Still, these bones and teeth closely match those of humans, the scientists say. Indeed, the Jebel Irhoud lower jaw also shares much in common with those of modern humans. All 22 Jebel Irhoud fossils qualify as H. sapiens, the scientists conclude.

Yet three braincases tell a different story. These include the newfound skull and two previously excavated, less complete specimens. Compared to braincases typical of humans, all of these are relatively long and low in height. In fact, the new braincases more closely resemble those of earlier species, such as H. erectus.

This would suggest that facial and dental traits of humans were established by around 300,000 years ago. Afterward, the brain’s shape continued to evolve, the researchers now propose.

Not everyone buys this argument. Among them is Erik Trinkaus. He’s a paleoanthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis. Homo fossils dating to between around 600,000 and 200,000 years ago typically contain some features recalling older species and other traits hinting at what would become H. sapiens, he says. Some of those fossils probably came from populations that were ancestors of modern humans. But that doesn’t mean those specimens — or the Moroccan finds — actually were humans, he contends. In fact, controversy simmers over the species identity of many fossils belonging to the Homo family tree.

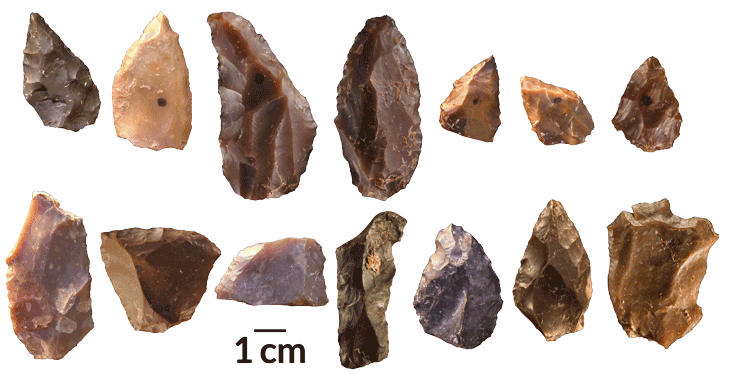

In a second paper, Daniel Richter (another Max Planck scientist) and his colleagues date 14 stone artifacts. These come from in and just above the soils in which the new fossils were discovered. Knowing how old these were allowed the researchers to narrow down the Homo fossils’ age to approximately 300,000 years ago.

Another 306 artifacts have been excavated by Hublin’s team. Together, these showed signs of having been heated in the past. A dating technique can gauge the time since rock or soil has been heated. Other new measurements of radioactive uranium in the site’s soil enabled dating the previously unearthed child’s jaw from the site. It now appears to be between 350,000 and 220,000 years old.

Most Jebel Irhoud stone tools were pounded off of larger rocks that had been prepared by toolmakers. This technique appeared across much of Eurasia and Africa by around 300,000 years ago — among both humans and Neandertals, the researchers say.