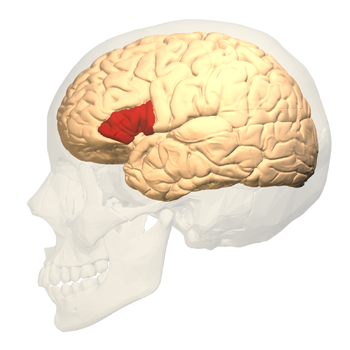

Stuttering: Blood flow in the brain may play a role

It is diminished in the language region known as Broca’s area

Stuttering is a disorder that causes halting speech.

TSchon/iStockphoto

By Lela Nargi

People once thought stuttering was just a symptom of being overly nervous. No more. Many people inherit their condition, and a new study points to blood flow as a possible contributor.

Stuttering causes halting speech. Myths about its cause and possible cures abound. People once believed tickling a baby too much could lead to stuttering. Others blamed it on having left a baby out in the rain. Some tried to cure the disorder by holding nutmeg under a stutterer’s nose or slapping the victim with a shoe. Some people still treat stutterers as if they’re unintelligent, or overly nervous. Even scientists have been stumped by what’s behind this language disorder.

Brain imaging, however, may just have filled in an important piece of the stuttering puzzle. Jay Desai is a clinical neurologist. He works at the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles in California. There, he uses a brain-scanning technique called magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, to observe blood flow in the brain. In a new study, he compared MRI scans of 26 stutterers (both adults and children) to those from 36 non-stutterers. No one spoke or moved while their brain scan was underway. That let Desai look for differences in their brains while “resting.”

These images showed that less blood flowed to the Broca’s area in the stutterers. Near the front of the brain, this region is involved in language and speech production. Blood flow to the Broca’s area was lowest in persons with the most extreme stutters.

Findings by Desai’s team will appear in an upcoming issue of Human Brain Mapping.

Psychiatrists once thought stuttering was due to stress or traumatic experiences. Studies instead have shown that inherited traits can play a role.

“Although we don’t have an answer for what gene may be responsible for stuttering, we now know that there’s a biological basis for it,” Desai says. Does low blood flow mean stutterers have less brain activity in Broca’s area? “We’re still not sure,” he says.

What he does know: Although 5 percent of children develop stutters when they’re learning to talk, three-quarters of them eventually outgrow it.

The new study does not explain what causes stuttering. But it may one day help researchers find a cure. “Is there a way to increase blood flow to this area, and will that work to treat stuttering?” Desai asks. That could prove a useful avenue of research.