Summer 2023 is when the ocean first turned ‘hot tub’ hot

Unfortunately, scientists suspect it’s the beginning of an unwelcome new ‘normal’

A sea turtle swims past a patch of bleached elkhorn coral at Alligator Reef in the Florida Keys on July 24. Ocean temps in the region hit record highs in late July, harming sea life.

Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

A fierce ocean heat wave in late July boosted temperatures in Florida’s coastal waters to never-before-seen highs. One buoy bobbing in shallows off the state’s southern West Coast hit 38.3˚ Celsius (101˚ Fahrenheit). Scientists suspect this may be the hottest ocean temperature ever recorded — not only here in Manatee Bay, but anywhere!

Within a week, that water had cooled somewhat. But South Florida’s sea life is still in hot water.

The temperatures recorded at Manatee Bay were shockingly high, hot-tub levels. In fact, they actually were “close to the limit of hot-tub temperatures” — and stayed that hot for several days in a row, says Benjamin Kirtman. He’s a climate scientist. He works at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science.

By August, Florida’s coastal temps had returned to a normal summertime range. But the danger remains acute for many ocean dwellers, from corals to fish, says Andrew Baker. He’s a coral biologist at the Rosenstiel School.

Ocean heat waves are becoming the new normal. Climate change now causes sea-surface temperatures to frequently rise well above the baseline warmth of the global ocean. This summer, Florida’s waters may have hit a record high. But July saw widespread ocean heat waves not just in the Sunshine State. Unusually high warming spanned from the North Atlantic Ocean to the eastern equatorial Pacific and on into the Southern Indian Ocean.

“The global oceans have warmed up so much … we’re seeing a ratcheting up that’s unprecedented in the modern instrument record — and maybe in the last 125,000 years,” Kirtman says. “It’s really quite remarkable.”

‘Way outside . . . anything these corals have experienced’

The North Atlantic’s brutally hot water in June and July arrived at the same time as steamy temps on land. This summer, Miami’s heat index, a measure of air temperature and humidity, soared to a record-breaking streak that lasted nearly two months. It hit a daily heat index of 38 °C (100 °F).

Swirling sediment leaves Manatee Bay murky. So it isn’t home to corals. But the temperatures in the reefs around the Florida Keys were still “incredibly hot” — perhaps hitting 36 °C (96 °F), Baker says.

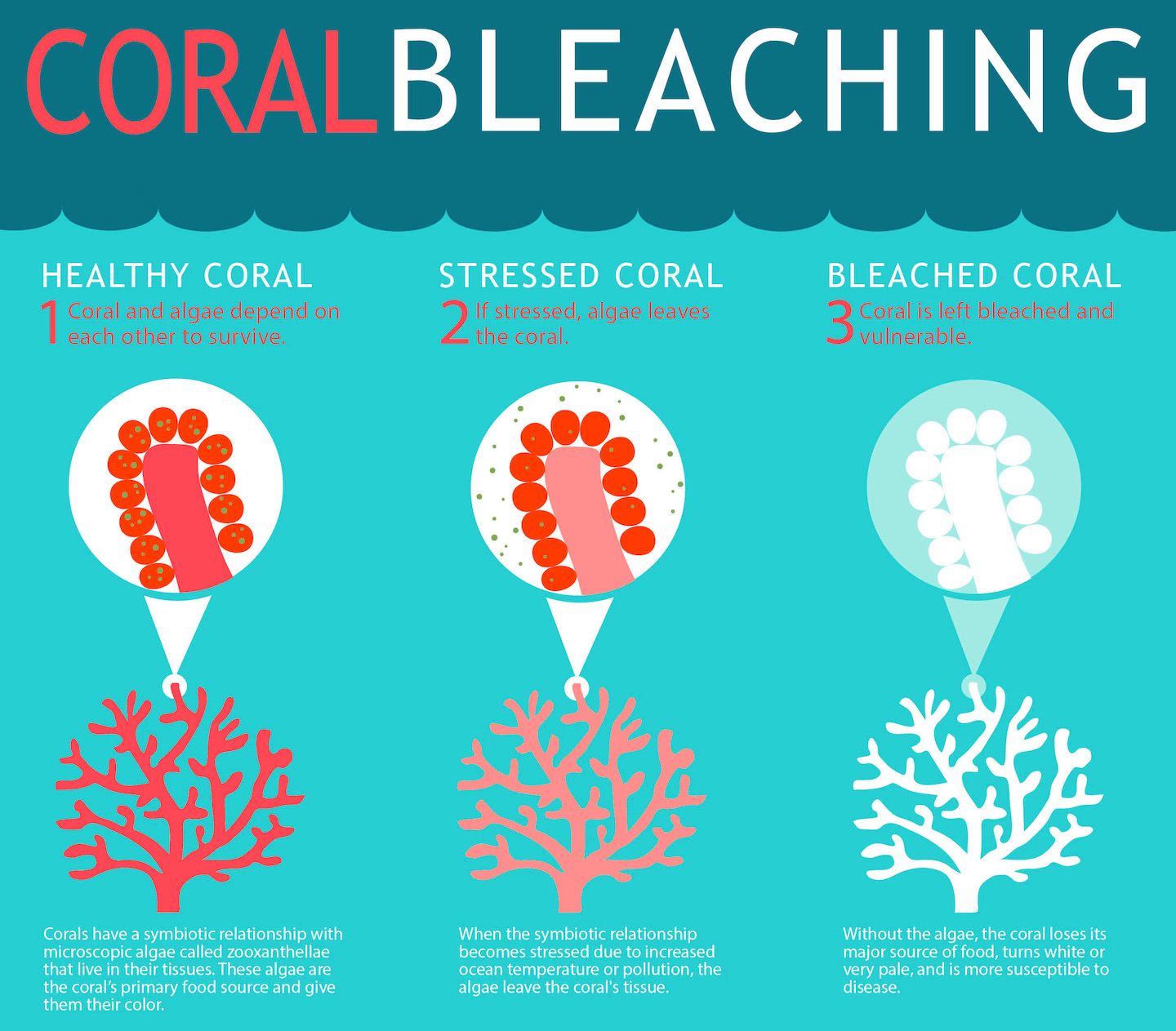

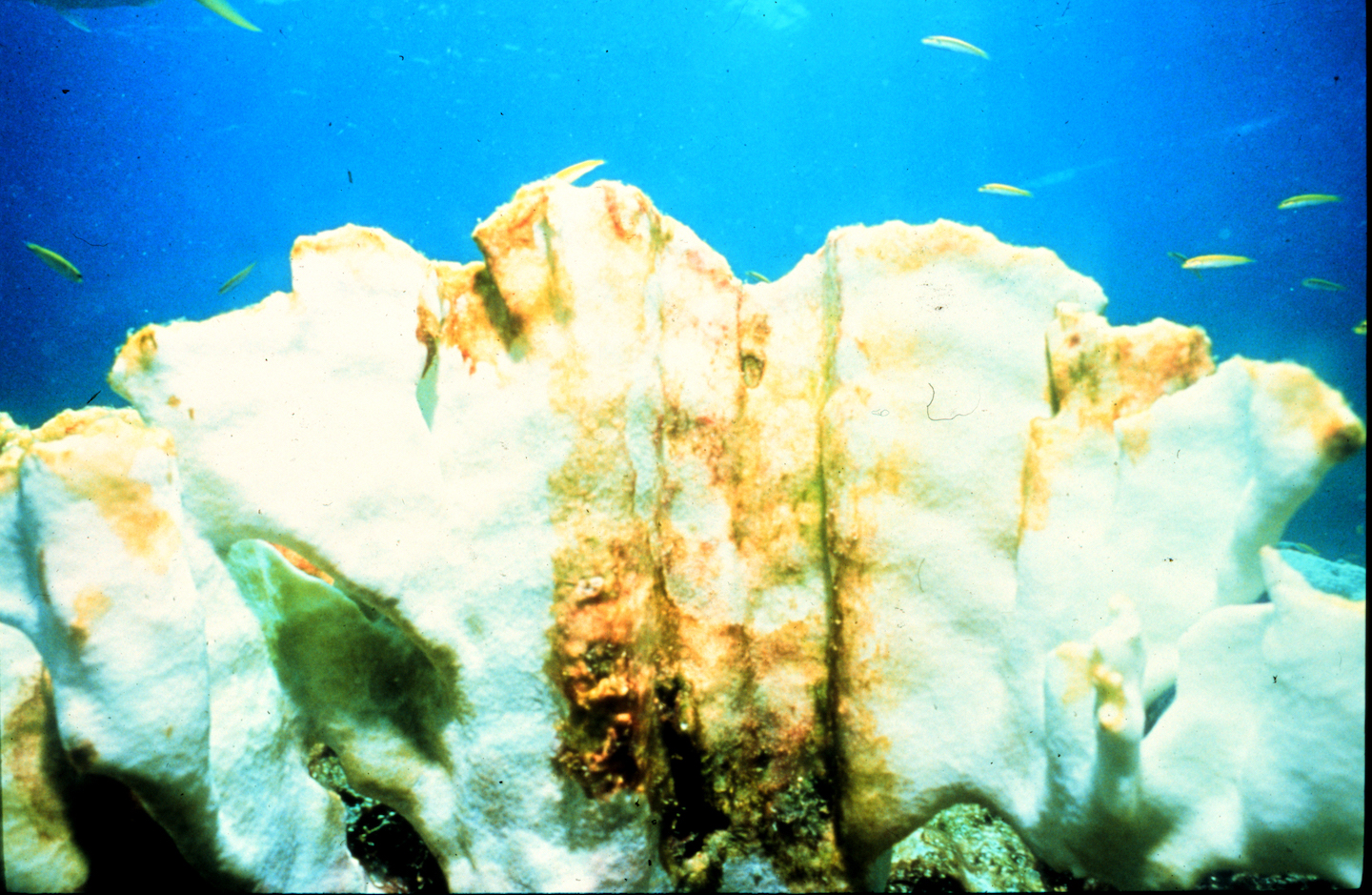

As the sea’s heat peaked around South Florida in July, nearby corals suffered. The Coral Restoration Foundation is a nonprofit ocean conservation group based in Key Largo, Fla. It found total death of coral at one site off Key West: Sombrero Reef. There, heat had caused the corals to bleach. They literally turned white as they lost the colorful algae, known as zooxanthellae, that normally live in their tissues.

Story continues below image.

Those algae are symbionts — organisms that help their host (because it also helps themselves). These algae make food, which they’ll share with the coral. When hot water makes the algae flee, the corals turn white and can eventually starve.

Corals can recover from bleaching that doesn’t last too long or occur too often. U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) records show that the heat burden on corals across the seas has been rising since the 1980s.

Even with the return to typical summertime water temps off Florida’s coasts, the impacts of July’s heat wave on the region’s corals will linger. That’s because corals have a limit to how much accumulated heat they can stand before bleaching. By the July heat spell, corals there had already received far too much heat far too early in the summer, researchers say.

Through July, NOAA records from sites across the Florida Keys each tell the same story — that 2023’s heat is “way outside of the bounds of anything these corals have experienced,” Baker says. And at that point, the summer still had months to go.

Helping out heat-stressed corals and more

For now, scientists are racing to save corals. Some are growing baby corals at nurseries in Florida’s keys. They start by collecting overheated corals from coastal waters. In onshore laboratories, these babies will be nurtured as part of a decade-long effort to protect the region’s two most important reef species — staghorn and elkhorn corals.

The fledgling finger- to hand-sized corals will be cultivated in coastal waters atop bits of white plastic tubing. Ultimately, they will be replanted back in the ocean.

As the water temps climbed this summer, researchers hurried to collect the cultivated corals ahead of their expected spawning in early August.

Scientists feared the heat would be “just too much for these baby corals.” They worried the animals might not spawn at all, Baker says. Happily, some of the rescued staghorn corals — now living in a lab — did spawn. On August 3 they released clouds of eggs and sperm into the water.

Whether the sperm will fertilize the eggs remains uncertain. But Baker and others are hoping for the best.

But what about everything else, from sponges to seagrasses to fish? A lot of studies show that ocean heat waves may push mobile species to seek cooler water, says Regina Rodrigues. She’s a physical oceanographer. She works at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Brazil. Her concern: In tropical regions like the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, those cooler waters may be just too far away. A community there, she says, may find it “doesn’t have anywhere to go.”

No escape route to cooler waters may leave this region’s cold-blooded sea dwellers, including fish, even more vulnerable to warming than species on land. A 2019 study found that cold-blooded species in the ocean typically spend more time than warm-blooded species at or near the upper range of temperatures that their bodies can withstand.

Another problem: As water heats up, it can hold less oxygen. Think of the bubbles that escape a pot of boiling water on the stove. That escaping oxygen leaves less behind for sea dwellers. Such hot, oxygen-depleted water has been linked to increased die-offs of seagrass. That can leave manatees and other animals that feed on them hungry. Fish also suffer in low-oxygen water. In June, for example, thousands of fish killed by a low-oxygen event washed up on the Gulf Coast just south of Houston, Texas.

‘It’s just bonkers hot’

What’s driving the oceans to reach hot-tub temperatures is still uncertain. However, scientists say, human-caused climate change is undeniably at its core. “Ninety-three percent of the excess heat in the atmosphere is being absorbed by the ocean,” Rodrigues says. That’s raised the average ocean temperature. “And once the mean temperature is raised, the extremes are easier to achieve.”

Other factors likely play a role, too. Consider the onset, this year, of the El Niño. It’s part of a system known as ENSO. The El Niño phase of this tends to increase average temperatures across the globe. And this year’s El Niño threatens to be “a strong one,” Kirtman says.

Some of that heat is due to how climate varies naturally, from year to year. The big question, he says, is how much that overall warming is now caused by “a ratcheting up of climate change.”

Local extremes — such as the temporary hot tub in Manatee Bay — may also be influenced by factors such as how shallow the water is. Or maybe it’s affected by the water’s murkiness. Water full of debris may just absorb more heat.

However, Kirtman says, the global oceans have warmed up so much that El Niño or murky waters alone can’t possibly explain what’s going on. “It’s just bonkers hot!”