The sun’s giant heat elevators

Mega-plumes of plasma move heat from inside of the sun around and through its outer layers

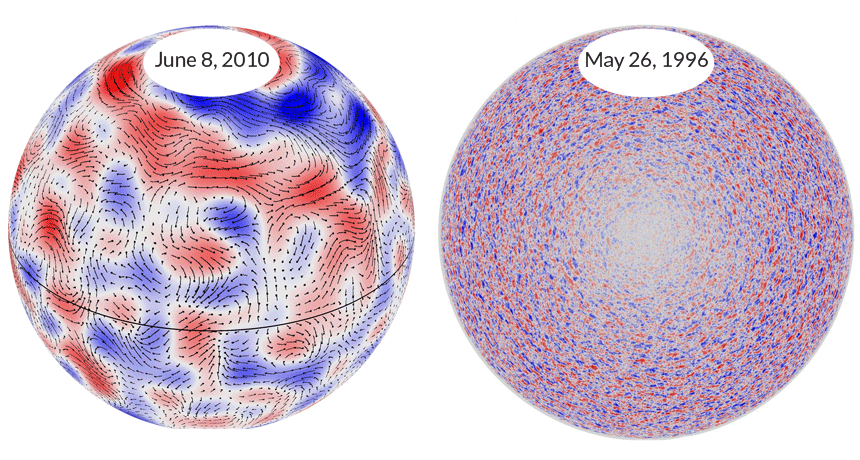

(Left) This illustration shows large granules bringing heat from deep inside the sun to its exterior. Blue areas show plasma flowing east to west. Red areas flow west to east. (Right) This illustration shows smaller plasma flows that were observed more than 15 years ago.

COURTESY OF D. HATHAWAY/NASA