Sun’s nearest stellar neighbor may have Earth-like planet

Its solar system is only 4.2 light-years from ours

Here’s an artist’s view of the surface of the planet Proxima b, with its red dwarf star just over the horizon. The double star Alpha Centauri AB also appears in the center of the image, just to the upper-right of red star.

ESO/M. Kornmesser

Earth may have a kindred planet no farther away than the star next door.

It’s a world at least 1.3 times as massive as Earth that orbits a dim star 4.2 light-years away. That star, alled Proxima Centauri, is the one closest to our sun. Its newly discovered planet whips around its star so fast that each year on that world lasts a mere 11.2 days. That reflects the fact that this planet is so close to its sun — just 5 percent as far as Earth is from our own sun. Yet that other world is at just the right distance from its star for any liquid water to still be able to flow on its surface.

That makes this exoplanet — a world outside our solar system — the closest known.

“It’s not clear if the planet will be Earth-like,” says Guillem Anglada-Escudé. This astronomer at Queen Mary University of London, England, led the exoplanet’s discovery team. As the nearest planet outside our solar system, this newfound Proxima b (not the most creative of names for a planet) is an attractive target to learn about alien atmospheres. It also may be a great place to hunt for signs of extraterrestrial life.

Anglada-Escudé’s team offered the first report on this planet August 25 in Nature.

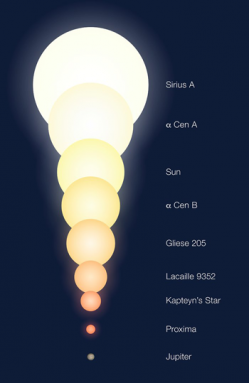

As star’s go, Proxima Centauri is a runt. It lies in the southern constellation Centaurus. Temperatures on its surface run about 2,800 degrees Celsius (5,000 degrees Fahrenheit) cooler than on our sun. The result: Proxima glows a feeble red. The star’s size is much closer to that of Jupiter than our sun. And despite it being so close, Proxima cannot be seen with the naked eye. That’s why it wasn’t discovered until 1915.

Proxima Centauri is part of a triple-star system known as Alpha Centauri. Four years ago, astronomers reported in Nature that another star in this group — Alpha Centauri B — hosts a planet roughly as massive as Earth. That world, however, would likely be too hot to host life. But not all scientists accept that such an exoplanet even exists there. Researchers last year reported in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters that they could find no evidence for the planet.

But Proxima’s planet seems real. And if it is, “It’s an incredible discovery; it’s almost a gift,” says David Kipping. He’s an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

How they found the new planet

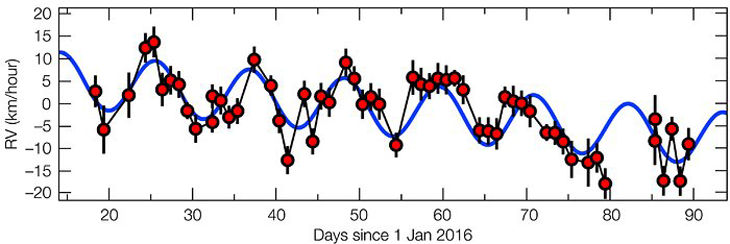

Anglada-Escudé’s group found its quarry by looking for a super tiny wobble in the position of its star. That wiggle would be due to a gravitational tug by the orbiting planet. For two months in early 2016, the astronomers led an intensive viewing campaign to follow up on early hints of a planet. They used two instruments in Chile. One was the European Southern Observatory’s 3.6-meter telescope. The other is known simply as the Very Large Telescope.

(Story continues below image)

Details about our not-too-distant neighbor remain skimpy. There’s no data yet on what its atmosphere is like. Even its precise size remains uncertain. And although it is just one star away, “we will likely have to wait a long time in order to learn anything more about the planet,” says Heather Knutson. She’s a planetary scientist at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif.

For now, Knutson says, the best bet is to hope that the planet, when viewed from Earth, passes in front of Proxima Centauri. That would allow its starlight to filter through the planet’s atmosphere. Gases in that atmosphere would betray their presence by absorbing specific colors of light. And they could point to more than just what makes up that atmosphere. The presence of oxygen, methane and carbon dioxide, for instance, are widely considered chemical markers of life.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is due to launch in late 2018. If the exoplanet does pass in front of its star, that space telescope should be able to detect its atmosphere, says Mark Clampin. He’s an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. Hundreds of hours of telescope time would need to be dedicated to the task. “It will be an extremely challenging observation, but not impossible,” he says.

Scientists can estimate the newfound planet’s size by measuring how much light it blocks as it passes in front of its star. That size, combined with its mass, could tell researchers something about how dense it is. At issue is whether this planet is puffy and gassy like Jupiter or rocky like Earth.

Kipping has already been monitoring Proxima Centauri with Canada’s MOST satellite. He’s been looking for a telltale periodic dip in the star’s light. That dip would be caused by the planet partially blocking its star. There’s only a 1.5 percent chance, however, that the planet lines up just-so with its star. And there’s a second problem. The light from Proxima Centauri tends to vary somewhat. That will make any additional drop in brightness from the planet passing in front of it hard to detect.

If things are not lined up just right, gaining more data on the planet will be “much more difficult,” Knutson says. Astronomers would have to rely on light coming from the planet. That would have to be either an intrinsic infrared glow (of heat) or some visible light reflected from its sun. The James Webb Space Telescope might be able to barely sense infrared light coming from Proxima b. But it could be at least a decade before any other instrument is up to the challenge.

And even then, there are no guarantees. “It’s going to be very difficult to characterize the planet without sending a probe there,” Kipping says. By probe he is referring to a spacecraft.

Planning a visit to the new world

A research team hopes to send out just such a probe. Many probes, actually. Their project is known as Breakthrough Starshot. In April, it announced a plan to put $100 million toward developing new technology that could send a fleet of tiny nanocrafts toward Alpha Centauri. Each robotic probe would weigh just a few grams. Researchers would nudge them on their way using an Earth-based 100 gigawatt laser.

The goal would be to accelerate them to roughly 20 percent the speed of light. If successful, this armada might be able to reach Alpha Centauri within 20 years of its launch. Quite a boost in technology would be needed to do this. For instance, it would take the fastest spacecraft ever to leave Earth — the New Horizons mission to Pluto — nearly 90,000 years to complete this journey. And that’s if it continued traveling at its current speed of about 52,000 kilometers (32,000 miles) per hour.

(Story continues below video)

H. THOMPSON; ESO (CC BY 4.0); M. KORNMESSER; M. TURBET; I. RIBAS; L. CALÇADA; G. ANGLADA-ESCUDÉ; NICK RISINGER/SKYSURVEY.ORG; PHL @ UPR ARECIBO; NASA; J.L. HEFFERMAN (CC BY-NC 3.0)

The new announcement by Anglada-Escudé’s team “is likely to energize the [Breakthrough Starshot] project,” says Avi Loeb. He’s an astrophysicist at Harvard and chairman of Breakthrough’s advisory committee. The goal would be to send back photos taken by a camera and various filters. Ground-based researchers could then use them, Loeb says, to infer whether that planet “is green (harboring life as we know it), blue (with water oceans on its surface) or just brown (dry rock).”

If anything is alive on the planet, it likely would prove quite different from anything on Earth. Organisms that photosynthesize — turn light into food — would have to deal with a faint, cool star. That star emits mostly heat, not bright light. Proxima Centauri also is known to host exuberant flares. They would buffet any near-orbiting planet with bursts of potentially killer conditions: ultraviolet radiation and X-rays. As a result, “conditions on such a planet would be very interesting for life,” says Lisa Kaltenegger. She works as an astrophysicist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

Scouting for alien life

Given such an alien environment, life might show up in unusual ways. Kaltenegger and Cornell astronomer Jack O’Malley-James propose looking for a glow. They call this glow biofluorescence (BY-oh-flor-ESS-ents). It would come from some of the planet’s organisms. They envision it might be triggered by the ultraviolet light emitted following those periodic flares by its sun.

Critters on Proxima b might have evolved biofluorescence as protection. They might be able to transform harmful ultraviolet light into more comfortable visible light. And this could show up as a flicker of light picked up by an Earth-based telescope.

“The idea that we could spot a glow seems to be right out of a [science fiction] novel,” admits Kaltenegger. She described the concept online August 24 on arXiv.org.

That all assumes that something could survive on the planet. If Earth were placed in the same orbit as Proxima b, it would lose its protective stratospheric ozone layer roughly three times every Earth-year, Kipping says. Obviously, he adds, “That’s kind of bad.” That would be too fast for the atmosphere to build its ozone layer up again.

But if life has taken shelter underground or underwater — or doesn’t need oxygen — it still might survive.

Whether or not critters crawl on Proxima b, the discovery of the planet “could really usher new energy into the search for other nearby worlds,” says Margaret Turnbull. This astronomer works with the SETI Institute in Madison, Wisc. Most exoplanets are hundreds to thousands of light-years away. But little is known about the possible planet families huddled up to the stars nearest to us. “I’d love to see interstellar travel,” says Turnbull. “To really inspire that kind of effort, we need interesting destinations like this.”