Supertiny satellites launched

Researchers are building simple, miniature satellites to bring down their costs and expand their availability

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Sid Perkins

You don’t need a big satellite to do big science. Smaller satellites can cost less to make. So even small research teams can rather inexpensively rocket their instruments into orbit. One group has just launched tiny telescopes this way to study stars.

The Hubble Space Telescope may be the most well-known instrument orbiting Earth today. It is also huge. At 13.2 meters long, it’s about the length of a school bus. And at more than 11 metric tons, it weighs about 50 percent more than an elephant! It’s so big and heavy that it had to be carried into orbit by the space shuttle Discovery in 1990.

The Hubble Space Telescope makes beautiful pictures and can see to the edges of our universe, but it is also very expensive. By some estimates, it has taken about $10 billion to design, build, launch, maintain and operate this telescope.

Because Hubble orbits high above Earth’s atmosphere, the telescope can see objects in wavelengths of light normally blocked by air. More importantly, it can make observations at any time of day or night. But even with a round-the-clock schedule, there’s not enough time available for all the scientists who would like to sign up to use this telescope, says Cordell Grant. He’s an aerospace engineer at the University of Toronto in Canada.

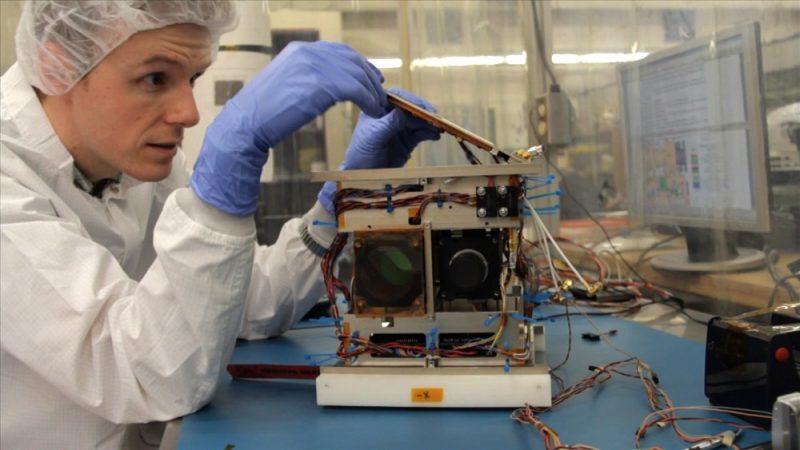

So, Grant and his coworkers have joined the ranks of scientists designing their own satellites. These craft can be much smaller than typical satellites, says Grant. Depending on the instrument’s size, researchers call these micro- or nanosatellites. (Taken from the Greek language, “micro” means small and “nano” means dwarf. In the metric system, “micro” means “one-millionth” and “nano” means “one-billionth.” Though these satellites aren’t microscopic, they are miniature, the smallest being roughly the size of a volleyball.) Because these spacecraft tend to use simpler sensors than those on typical satellites, these tiny satellites can be relatively inexpensive to build, outfit and launch, says Grant.

For instance, the nanosatellites that Grant and his team recently designed were built to do one simple thing: observe some of the brightest stars in the sky. They’ll measure the stars’ brightness within very narrow ranges of wavelengths of light. These measurements of brightness and “color” offer clues to a star’s size, distance and age.

By repeating those measurements over two years or more, astronomers can detect short- and long-term changes in a star’s brightness. That could help researchers identify spots on a star, which, similar to our parent star’s sunspots, might indicate concentrated magnetic activity. It could even help scientists discover when something passes in front of a star, temporarily blocking its light. That’s how astronomers identify some distant exoplanets.

Previous mini-satellites were launched to show that certain types of components or observation techniques would work well in space. The new team’s nanosatellites, by contrast, are designed to do real work. “This isn’t just an educational exercise,” says Grant. And, he adds, “these are the smallest space telescopes ever launched.”

Each of the nanosatellites weighs about 7 kilograms, about as much as a bowling ball. Each is a cube that measures about 20 centimeters on a side, making each unit a little smaller than a box designed to hold a volleyball. The telescope on each craft is mounted so that it looks out of one side of the cube. All six sides of each craft wear solar cells to generate enough power to run the nanosatellite and its instruments.

Besides saving money by using a simple design, the tiny satellites’ makers also saved money by having the craft ride piggyback into space on a rocket that was already launching a much larger and costlier satellite. Altogether, each of his team’s nanosatellites costs relatively little, Grant says — between $1 million and $2 million.

“It’s almost reached the point that any organization that could never have afforded a telescope of its own can afford one now,” says Kieran Carroll. He’s an aerospace engineer at Gedex Inc. in Mississauga, Canada. That company helps develop instruments that can be carried by planes and used to find mineral resources. Previously, Carroll worked at a company that designed small satellites, just as Grant does at his university today.

The new nanosatellites designed by Grant’s team were launched from India on February 25. Now they are orbiting about 800 kilometers (500 miles) above Earth. They circle the planet once every 100 minutes. This gives Earth-bound scientists several opportunities each day to communicate with and retrieve data from the satellite as it passes overhead.

Micro- and nanosatellites offer plenty of promise, says Carroll. For example, their sensors can view Earth in infrared wavelengths, ones people cannot see. With such sensors, scientists could look down on Earth for “hot spots” that betray the presence of forest fires. Or, orbiting microsatellites could measure water vapor in Earth’s atmosphere, Carroll notes.

And mini-satellites can be fun. “Big satellites can be too intimidating,” Carroll says. It used to be that the only way to get into the satellite business was to work on some small project being developed as part of much bigger program. “Now, engineers can be a part of a small team and be involved in a project from start to finish,” he explains.

Power Words

engineer A person who uses scientific knowledge and principles to develop solutions to technical problems. An aerospace engineer, for example, can design new aircraft and satellites. They can also analyze existing aircraft or satellites, measuring their performance in order to suggest or design improvements.

exoplanet A planet orbiting a star other than our sun, meaning it’s outside our solar system.

nanosatellite: A satellite that’s much smaller than typical space probes. “Nano” is a Greek word that means “dwarf.”

wavelength (of light): Light, or electromagnetic radiation, is characterized according to its wavelength. Visible wavelengths range from red to violet, but all other wavelengths — including X-rays, gamma rays, radio waves and microwaves — are invisible to the human eye.