Earthquake sensor: Taylor Swift fans ‘Shake It Off’

Dancing Swifties made seismic waves during Eras Tour performances last August

Taylor Swift performs March 17, 2023 — opening night of the Eras Tour in Glendale, Ariz. Dancing fans at later concerts in Seattle, Wash., and Inglewood, Calif., shook the stands hard enough for nearby earthquake sensors to detect.

Kevin Winter/Staff/Getty Images Entertainment

Taylor Swift fans really know how to “Shake It Off” — and shake the ground.

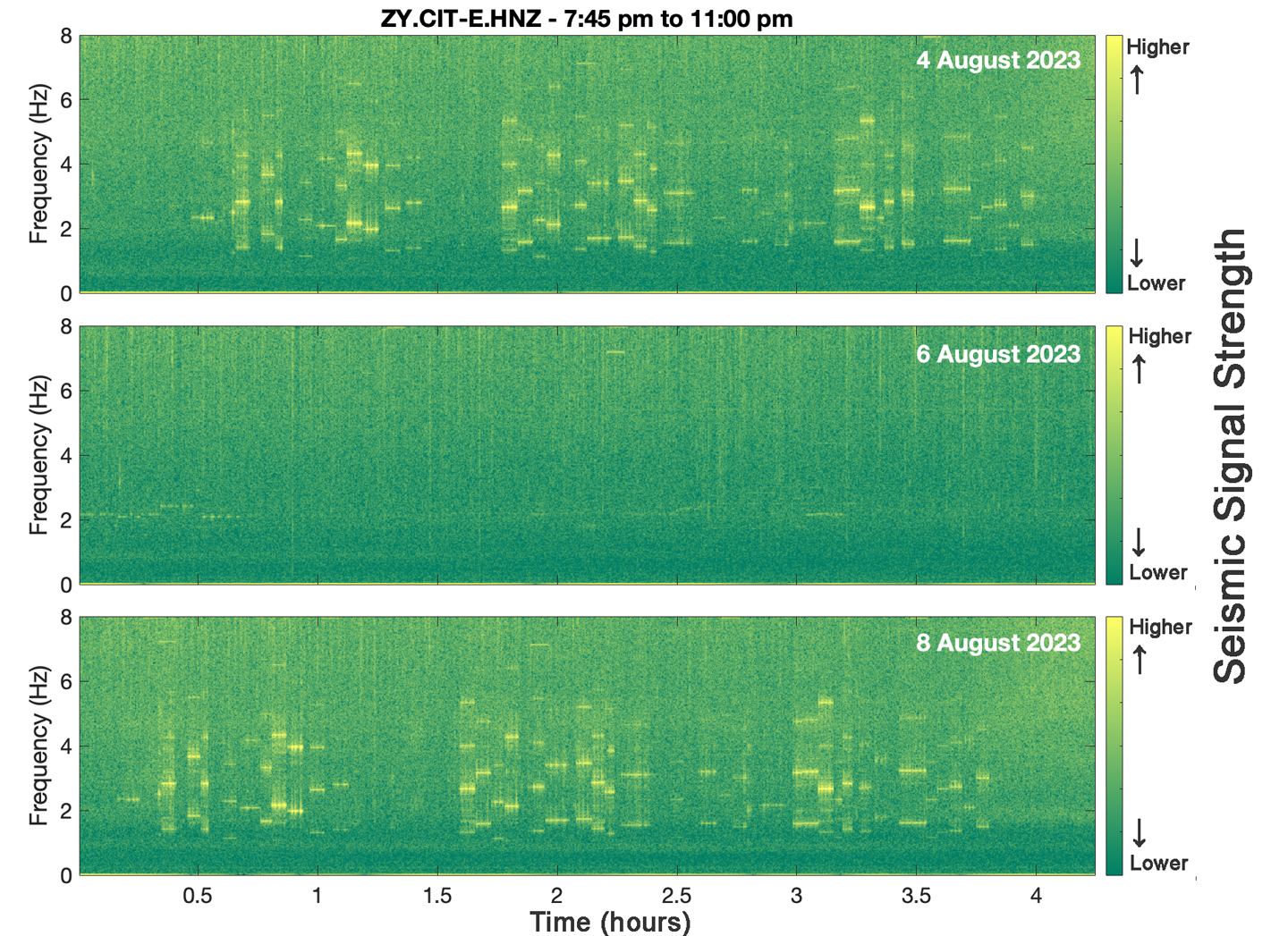

Scientists studied how the stadium and ground trembled during one of Swift’s Eras Tour concerts last August. They found that dancing fans generated vibrations in the ground — seismic waves that matched the beat of each song.

The team shared its findings March 13 in Seismological Research Letters.

“It’s really fun to be able to use seismic tools to understand things like music and concerts and events that bring people together,” says Eva Golos. A seismologist, she studies earthquakes but was not involved in the new research. Golos works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Stadium vibrations

This isn’t the first time seismologists have measured vibrations from a stadium. In 2011, Seattle Seahawks fans shook their home stadium with cheers after a stunning touchdown. And last July, Swifties rattled the ground at a Seattle concert.

The shaking from those events differs from an earthquake. Earthquakes usually last only a few seconds. A “concert tremor,” in contrast, can last several minutes.

The ground also moves in different ways during quakes and concerts. Earthquakes happen when huge slabs of Earth’s crust, called tectonic plates, shift around. Those motions permanently change the ground. The shaking caused by crowds doesn’t usually deform the Earth.

Concert tremor “is more like splashing on a puddle of water,” explains Gabrielle Tepp. She’s a seismologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “You see the ripples coming out, but then once you’re done splashing, it just goes back to normal.”

Seismologists use similar instruments to detect earthquakes and concert tremors. In the new study, Tepp’s team set up motion sensors in and around SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, Calif. They did this right before Swift’s first Eras Tour performance there. Those instruments measured shaking from the stadium during Swift’s concert on August 5, 2023. Some 70,000 people attended that show.

For many of the songs performed that night, the frequency of the vibrations lined up with the beat of the song. The researchers could identify almost every song that Swift performed using the frequencies and durations of the vibrations.

The stadium shook most during Swift’s performance of “Shake It Off.” During that song, the stands released about as much energy as a magnitude 0.85 earthquake. That’s not quite strong enough to be felt by humans, but it releases as much energy as blowing up a few ounces of TNT.

That energy was released over the full length of the song. An earthquake (or a TNT explosion) usually releases all of its energy in a few seconds.

The difference between an earthquake and a concert tremor is like “the difference between a firework explosion and a jet engine roaring,” says Tepp. “They might release the same amount of energy. But the explosion is happening very quickly. It’s all at once. Whereas with a jet engine, you’re releasing [energy] over a longer amount of time. So it’s not as loud at its peak, but it goes on for much longer.”

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Finding the seismic source

Tepp and her colleagues wanted to identify what was causing the Swift concert tremor. Was it jumping fans, the sound system or the instruments?

To find out, the team set up a portable speaker next to a motion sensor in their lab and turned the speaker volume all the way up. Then Tepp plugged in her bass guitar and played a simple beat over the speakers. They also blasted Swift’s “Love Story” at the speakers’ highest volume. Tepp even jumped around near the sensor while grooving to the last chorus.

The sensor picked up vibrations that matched those from the concert only when Tepp was jumping around. That suggests that the vibrations measured on August 5 came from fans jumping and dancing, too.

The findings tell scientists about more than just concert tremor. Understanding how a stadium shakes in response to a large crowd could help make buildings safer, says Golos. “We can also better understand human behavior” using such seismic data, she says. “I think there’s a lot of interesting information hidden in there.”