A teacher’s guide to mentoring in STEM

How to find and be a good mentor in STEM

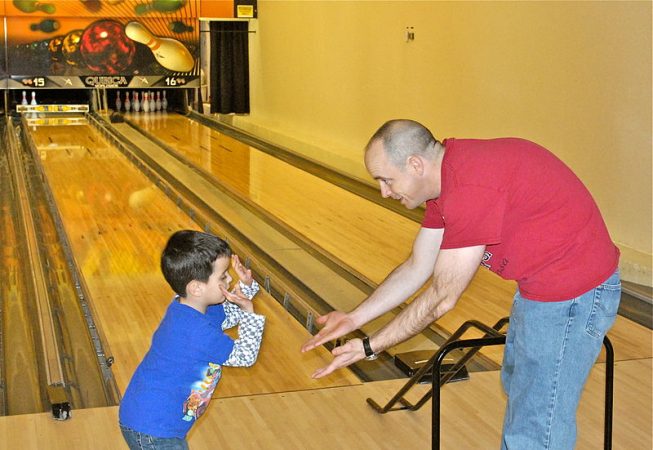

Mentors that are involved in students’ lives can keep them engaged and encourage them to pursue STEM careers.

dcdebs/istockphoto

There was once a girl named Beth who loved the environment. She took every course that her school offered in biology and environmental science. The teen studied science because she felt that it made her look smart. She also cared about environmental issues and liked to work outdoors.

But she did not study science because she was passionate about it.

That changed when Beth attended the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Va. There she met Paul Heideman. He taught animal physiology — the science of how animals’ bodies work. Often, he would bound around the front of the classroom, drawing furiously on his whiteboard. Other times he would make his students do silly dances to demonstrate scientific concepts. Before long, Beth was hanging around his office for hours. Heideman pushed her to look beyond what he taught in class and ask why the body works the way it does.

In short order — and to her immense surprise — Beth realized that she had developed a deep love of physiology. Suddenly, her science grades improved. She even decided to seek a career in science. And Heideman enthusiastically supported her.

After graduating from college, Beth moved on for more training — to graduate school. Throughout those years, she stayed in touch with her former professor. Along the way, he encouraged her to seek grants to pay for her research. He wrote a wonderful reference letter for her first grant application and later pushed Beth to publish her first paper in a scientific journal.

He congratulated her — which is to say me — on all of my successes. And he encouraged me to keep working through my failures. In short, he was an amazing mentor. He provided support outside the classroom and pushed my scientific curiosity beyond what he was teaching in class.

Guidance from the right person can fire up a passion for science, technology, engineering and math, also known as STEM. In fact, I credit my career in science today to the early support and inspiration provided by such a selfless and encouraging mentor.

Finding someone who can inspire a student to take on the demands of STEM research can be challenging, though. Students vary widely in their backgrounds, training and interests. And what they need from a mentor will evolve as a student matures. But a good mentor can make the difference between someone who chooses a career in STEM — and someone who walks away.

Here, we explore mentoring and how to make it a win-win relationship for everyone involved.

Not necessarily a role model

When students seek a mentor, they need more than someone who will give them a dishwashing job in their laboratory or respond to their emails, says Mary Fernandez. She runs the New York City-based Mentornet. This group helps match up students who are interested in STEM fields with mentors who can give them career support and help them pursue opportunities. A listening ear and bit of empathy can make the difference between a professor dispensing advice and a mentor who understands a student’s desires and needs, she says.

Yet students often look for mentoring from the wrong source, such as a role model, observes Kate Goddard. She manages outreach and online communications for the National Girls Collaborative Project. It’s an umbrella program based in Lynwood, Wash., that brings together smaller groups to encourage young women in STEM careers and to encourage their success.

Kids often admire role models for the cool things they do or their great achievements. This can make role models very influential. That’s why Goddard started FabFems within the National Girls Collaborative projects. FabFems is a directory of women in STEM who can help teachers find female role models to inspire their students.

But being a great role model may not translate into being a good mentor, Goddard warns.

“The point of a role model is to break stereotypes,” she explains. “A role model is more of a one-time experience, where students can see and identify with someone, and be inspired to be them.” Because few students will see a role model more than a few times, they rarely develop a deep relationship with such an individual. As a young girl, I was inspired by Jane Goodall. But I have yet to meet her. She was a role model, but for a mentor, I needed someone more accessible.

Good mentoring requires time and, above all, an emotional investment. “The most important quality in a mentor is, first and foremost, to have empathy,” argues Fernandez.

Athena Andreadis is one such individual. A former molecular neurobiologist, she is now a writer and editor in Cambridge, Mass. Over the years, Andreadis has helped guide people at all stages of their research and writing careers. She agrees that mentoring is not just about pushing someone towards a particular job or educational path. A mentor must be able to see the world from a student’s point of view.

Mentoring do’s and don’ts

“Mentors should not impose their values on the mentees,” says Alberto Roca. He’s the executive director of DiverseScholar. This online program, based in Irvine, Calif., provides guidance and resources to STEM students from under-represented groups. Effective guidance, he says, requires listening closely. Mentors must learn what students want in a career, what they want for their personal lives and how their backgrounds might differ from their own. That information can then guide the mentor’s advice and actions.

Some students come to a mentor with clear ideas of what they need but may not articulate it clearly. Others may not even realize what areas they need to develop or strengthen. Listening carefully to subtext can help mentors understand what a mentee needs to succeed.

Often, a student will tell a mentor what they need “without even realizing that they are doing it,” observes Rachelle Oldmixon. A psychologist in Los Angeles, Calif., she’s a contributor on Al Jazeera’s weekly science video series, TechKnow. She describes her recent experience tutoring high school students who were studying for a college entrance exam, the SAT. One student had been struggling for weeks to get his ideas onto paper. At his last session after a preparation test, he asked his mentor: “Why did I get a good score in the ‘supporting sentences’ section? I didn’t think I would.’” His confusion gave Oldmixon the clue to his struggles: The student had never been taught how to write an essay.

Careful listening can help mentoring relationships grow. Oldmixon says her own relationships with mentors as she was growing up were “a lot like friendship. My best mentors treated me as an equal. All of my ideas were valid.” Because of this, Oldmixon notes that the mentoring relationship may end up being a much closer one than what a student develops with a teacher.

But mentors can be far more than just a friend with the skills and experiences that a student lacks. Mentors often provide guidance to help students succeed in their prospective careers.

That’s what Mark Chu-Carroll found. His college advisor kept Chu-Carroll’s career goals in mind as he advised him on what courses to take and what research to try. This advisor — and mentor — also introduced the young man to people who might help him get a job. He also told Chu-Carroll which computer languages might be most useful to learn. Today Chu-Carroll is a software engineer for Twitter in New York City.

Some students may benefit from having more than one mentor, each of whom tackles a different aspect of the student’s life. Melissa Wilson Sayres, a geneticist at the University of California, Berkeley, says she ended up with two professors in graduate school who mentored her as she prepared for her first research job. She describes the first as her motivator, someone who “believed” in her. The other “validating” mentor “helped me to believe in myself,” she explains.

Mentoring at every age

Many students don’t realize they need a mentor until college or graduate school, Fernandez says. But this doesn’t mean that a younger student doesn’t need or won’t benefit from having a mentor.

Indeed, Jean Rhodes emphasizes that mentoring is vital at all ages. A psychologist at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, she directs its Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring. Its scientists conduct research on mentoring to better understand which relationships are most effective. The center has shown in its Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring that the best mentoring relationships provide close, supportive bonds. These let students develop their own vision of what their lives should be like. Good mentors also encourage students to reach their potential.

What students need from a mentor changes as they mature. Younger kids, for instance, may be focused on forming personal relationships with an adult who offers guidance. These early mentors may be relatives or family friends. That was true for Jedidah Isler. Mom was her first mentor. The woman set high standards and instilled a good work ethic in her daughter, who is now an astrophysicist at Syracuse University and Harvard University.

Their close relationship never focused on physics, Isler says. Still, it taught her to focus on doing her best. Mom, she recalls, “first instilled in me the notion that I could do anything I put my mind to.”

As kids proceed through middle and high school, they will “begin to gravitate toward mentors that can guide them toward the career that they want,” notes Rhodes. A student interested in dinosaurs might seek out a paleontologist. A tween into conservation might be attracted to an aquatic biologist.

Middle school is an especially important time for STEM role models and mentors. This “is when kids really get disengaged with STEM,” says Goddard. “That’s also when they make decisions about who they want to be.”

Without mentors and role models, students may feel there are few people with whom they can relate on science or technical subjects. The net result, Fernandez says, is that many tweens and early teens — especially young women and minorities — leak out of the STEM pipeline.

Katherine Sebeck, a materials scientist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, says that her eighth-grade physical-science teacher had a huge impact on sustaining her love of science. That teacher “was the first confident, exuberant woman in STEM I met,” Sebeck says — at least the first one outside of her family. Best of all, she recalls, “She really taught me to be joyful about science and to have fun with it.”

Eugene Day, who works on patient safety at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, says his seventh-grade algebra teacher helped him love math. How? By making him realize “that sometimes even when I feel confused, I’m doing things right.” Building that self-confidence at such a critical time, Day believes, helped him to become the engineer he is today.

In high school, mentors can become even more crucial, as science and technology courses have fewer explosions, goop and games, and more lecture-oriented courses, memorization and tricky problem-solving homework. Mentors can provide guidance and remind students of the bigger picture.

Natasha Godard, a science blogger in Chicago, can relate. She credits her high-school science teacher with getting her beyond the “ick” factor during dissections by involving her as a teaching assistant with younger students and helping her to set up experiments to run on her own.

Finding mentors

In younger grades, instead of scouting for a mentor, students may rely on the one right under their noses. In elementary and middle school, mentors often are teachers.

Chris Thompson, a developmental neuroscientist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., says that he got lucky that his fifth-grade teacher turned out to be a fantastic mentor. “He would always give praise in such a way that made you feel like you really achieved something,” Thompson recalls. But he says his teacher’s disappointment was even more effective. That made it clear he knew how much Thompson could achieve. That disappointment always spurred the young boy on to perform better.

When a student needs a mentor outside the classroom, teachers and parents can offer guidance in finding one. “Some of the most effective [mentors] are those who are a bridge between a youth and another mentor,” says Rhodes of the Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring.

Lately, though, “we’ve moved toward encouraging students to find their own mentors,” she says. Her group teaches middle-school, high-school and college students how to identify their own interests, identify mentors and reach out to those people.

As a senior at Brookings (S.D.) High School, Zarin Rahman, 17, knew that she wanted to study how sleep affected teens at her school. She turned to the webpage of her hometown university, South Dakota State. “I found a professor whose area of expertise and interest matched my own,” she says. “I approached him via email and explained who I was and what I was interested in.” The professor replied immediately. And with that, a mentoring relationship was born.

Teachers helping students find potential mentors also can look to local groups that work with youth. Organizations such as 4-H and the United Way have national and regional mentoring programs. For girls and young women, there is the National Girls Collaborative Project and Girls Inc. The National Society of Black Engineers also offers programs focused toward middle school and high school. Students may find mentors through local programs, such as iPraxis in Philadelphia, Pa. Or teachers can help connect students with STEM professionals at local colleges.

Resources are available for those who wish to become better student advisors. Mentoring.org, for instance,offers training kits and webinars to teach people the basics: communicating with empathy, becoming an active listener and keeping conversations open and flexible.

It may take some effort, but being a good mentor can change a student’s life. “My mentor was the catalyst to who I have become,” says Godard. “She changed my life. And I will always be grateful.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on December 1, 2014 to correct the affiliations of Jedidah Isler.

Resources

Mentornet: A group providing mentorship for STEM students by matching students with professionals in their fields of interest using online social networks.

National Girls Collaborative Project: The NGCP helps STEM groups focused on women and girls find and collaborate with other groups in their area to increase their impact.

Center for Evidence Based Mentoring: A part of the University of Massachusetts in Boston, this center conducts research on mentoring strategies, and develops and disseminates materials to train mentors and establish mentoring programs.

US 2020: An organization that seeks to match one million STEM mentors with students, focusing particularly on girls, minorities and students from low-income families.

ACE Mentor Program: A group of industry professionals in architecture, construction and engineering providing mentoring relationships and practical experience in these fields.

TechGirls: An organization that provides hands-on experience in technology to girls and young women.

Mentoring.org: The National Mentoring Partnership is affiliated with the Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring. It provides resources to start mentoring programs and advocates for increased funding for mentoring organizations.

National Society for Black Engineers: A group that strives to increase African-American participation in engineering careers. It offers NSBE Jr., which offer resources, competitions and scholarships for young students interested in engineering.