Teen athletes with even mild COVID-19 can develop heart problems

Without rest, such damage might not heal, or it could even worsen

Kids who test positive for COVID-19 may feel no symptoms and want to continue sports and other exercise. But the virus can cause hidden heart risks that should be heeded. That’s why rest is good medicine for teens who get the new coronavirus.

AzmanL/E+/Getty Images

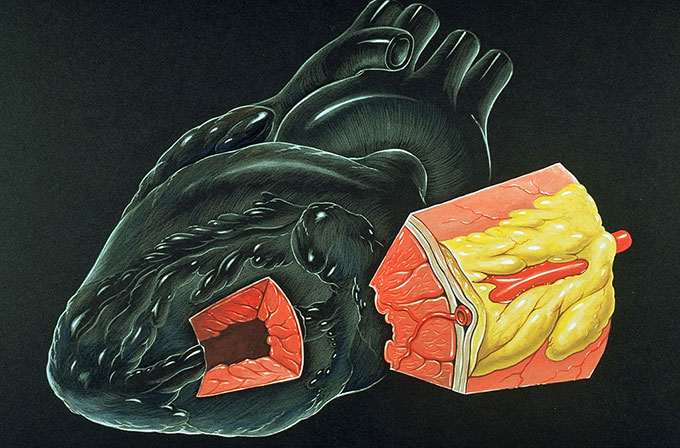

COVID-19 can do some pretty scary things to the heart. For instance, it can inflame or even scar heart muscle. A study now shows that such things can happen even to teen athletes who got mild coronavirus infections. Some had not even shown symptoms of the virus.

The good news: Most teens who become infected with the new virus will not suffer heart damage. The problem: It’s hard to know who will. That’s why I and other heart specialists are trying to get the word out. We want you to know that COVID-19 is not to be laughed off as only a threat to old people.

I am chief of heart medicine at West Virginia University School of Medicine. It’s in Morgantown. My team has been developing techniques to assess changes in heart muscle among people with COVID-19. This fall, we screened the hearts of 54 student athletes who had tested positive for the virus three to five weeks earlier. We found heart abnormalities in more than one-third of them. Most had developed either mild symptoms or none at all.

None of these athletes showed serious and worsening damage to their heart muscle. However, we frequently saw potentially dangerous inflammation in that muscle. We also saw high rates of a fluid buildup in a sac around the heart. That sac is known as the pericardium (Pair-ih-KAR-dee-um). Such a fluid buildup can become dangerous.

We published these findings November 4 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Imaging.

Based on results of this and other studies, the journal that published our paper brought together a group of experts. We were asked to interpret what such findings from new studies mean for student athletes recovering from coronavirus infections. We now conclude that “COVID-19 may cause potential long-term [heart and lung] complications in athletes.” We note that this also raises concern about when students can safely return to playing sports.

There is still a lot we don’t know about COVID-19 and its long-term effects. But the more we learn, the more we realize this is one viral disease we must all treat with respect.

COVID-19 is bad news for hearts

The virus that causes COVID-19 can cause a mind-boggling array of damage. This includes inflammation in the heart and surrounding tissues. That inflammation is one way the body tries to fight the virus. An August paper in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging shows that up to one in eight people hospitalized with COVID-19 have some form of heart damage.

What we most worry about in student athletes is whether the virus might trigger a rare inflammation of heart muscle. Known as myocarditis (My-oh-kar-DY-tis), it can limit the heart’s ability to pump blood efficiently. It also can lead the heart to beat too fast or too slowly. Such changes can further impair the heart’s ability to pump blood effectively.

Some college athletes with COVID-19 have been diagnosed with myocarditis. Luckily, there haven’t been many. That’s the finding of a September 11 study in JAMA Cardiology. Doctors at Ohio State University in Columbus tested 26 college students (many in their teens) who had COVID-19. These young men and women played football, soccer, lacrosse, basketball and track. Heart scans showed four had signs of myocarditis. Two of these four had never shown symptoms of their coronavirus infection.

Matthew Martinez heads sports cardiology, or heart medicine, at Atlantic Health System in Morristown, N.J. An August 10 ESPN news account quoted him as hearing from colleagues at more than a dozen colleges about student athletes recovering form COVID-19. A number of those students showed signs of myocarditis. Again, some had never shown coronavirus symptoms.

Taken together, these accounts suggest that viral myocarditis can show up even in athletes who seem healthy. In many cases, the injury to heart muscle may look minimal. The problem: It’s hard to know what the long-term effects of such changes will be.

Especially troubling, myocarditis can cause a rare condition known as sudden heart failure. Symptoms can include shortness of breath, irregular heartbeats, lack of appetite, nausea, difficulty concentrating and more. Heart failure can lead to kidney or liver damage or worsening effects in the heart. Clearly, it’s nothing to ignore. That’s why anyone with myocarditis should definitely not be on the playing field or in training.

But this isn’t the only heart problem that athletes recovering from the coronavirus need to worry about. There’s that pericarditis we saw. It causes swelling and irritation of the sac surrounding your heart. It will give some people sharp chest pains. If left untreated, it can cause serious complications and perhaps permanent heart damage. That’s why sports doctors for years have warned that athletes who develop pericarditis should not return to play until it is gone.

What we found in our student athletes

Thankfully, none of the 54 student athletes we examined had convincing signs of myocarditis. But many seemed to have pericarditis. We imaged the heart, using a dye to highlight changes. That dye lit up the pericardium in four out of every 10 of the athletes. This suggests the sac that protects their heart had been inflamed. A buildup of fluid in this sac showed up in nearly six in every 10 of the students.

With rest, these problem can usually heal on their own within a few weeks. Sometimes a doctor may also prescribe drugs to fight the inflammation.

The big concern is that there sometimes can be long-term impacts. For instance, the inflammation might come back, causing a scarring of the tissue. In rare cases, the sac can tighten around the heart. This can lead to symptoms similar to heart failure. It also can cause a fluid buildup in the lungs and liver.

It’s difficult to know which patient will develop any of these rare long-term impacts. In the students we screened, it was too soon to know that. Most of them seem to have improved and we have allowed them to return to play. Still we are closely monitoring them and following their hearts in this post-recovery period.

Advice for athletes

Currently, sports programs around the United States have different guidelines about when athletes who get COVID-19 can return to play. Guidelines also differ on which students should be screened for heart damage.

To help schools and other groups set science-based standards, I and other cardiologists from the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Australia reviewed emerging data. On October 26, we published a “consensus statement.” It identifies what is — and isn’t — known about COVID-19 heart risks in student athletes. That same day, some of the same doctors (including Matthew Martinez) authored a similar statement in another journal. It focuses on myocarditis. Why? As that statement points out, myocarditis is “an important cause of sudden cardiac death during exercise.”

Based on our reviews, we suggest that any student athlete who has gotten COVID-19 go into temporary quarantine. This will avoid exposing teammates, coaches or anyone else to the virus. Then, before returning to play, these athletes should consult with a doctor to see if heart-imaging tests are needed. This will not be needed for all symptom-free athletes. But only a doctor will know which patients face a high enough risk to need heart screening.

For any athlete who has active myocarditis, we recommend they avoid competition or strenuous training for three to six months. During that time, they should be checked out by a cardiologist. Why so long? Exercise can worsen this disease and create irregular heartbeats. In time, athletes can gradually resume exercise. They should return to play only after heart inflammation or altered heartbeat patterns are gone.

We also recommend cutting back on workouts in athletes with signs of active pericarditis. Exercise can worsen that inflammation or cause it to return. And these athletes should avoid all competitive sports until tests show no inflammation or fluid buildups around the heart.

Finally, I would like to see sports groups test student athletes, no matter their age, for the virus. Testing to date has focused on college athletes. But younger teens or preteens may face the same risks.

The new coronavirus is no joke. We want to see all young athletes continue to safely play sports. The best way to accomplish that in the days of COVID-19? Avoid getting the virus in the first place. But for those who do become infected, take it easy for a while — even if you feel fine — and then ask your doctor when to resume exercise. Your heart will thank you for it.

This article has been adapted with Partho Sengupta’s help from a piece this cardiologist wrote for The Conversation.