Teen brains may have an advantage — better learning

Adolescent brains may learn some things better than adult brains do

The teen brain is sensitive to positive feedback. These mental high-fives might help them learn some tasks faster and better than adults

cbarnesphotography/ iStockphoto

Teens can get a bad rap for their behavior. They tend to be more sensitive to rewards than to punishments. Indeed, teens tend to seek out rewards more than do adults or young kids. Those reward-seeking behaviors can cause nightmares for the adults in their lives. But a teen’s big interest in rewards might have an upside, a new study finds. Teens may tap it to learn some new things better than adults do.

The adolescent brain has a lot going on, notes Juliet Davidow. She’s a psychologist — someone who studies the mind — at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. Teen bodies are growing, she says. Their minds are too. A brain “changes just like the rest of the body changes,” she explains.

In a teen’s body, the hands and feet may grow bigger first, leaving the rest of the body to catch up. The brain is no different. Some of its areas mature early. These include the striatum (Stry-AY-tum), which recognizes rewards. The prefrontal cortex, which helps in decision making, matures later.

This means teens tend to be find rewards super enticing. At the same time, teens often fail to plan — especially during times of stress.

B.J. Casey is a neuroscientist — someone who studies the brain — at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. The media and the public often depict the teen brain as a defective car, she notes. The describe it as having “no steering wheel and no brakes, just an accelerator.” Many scientists, including Casey, think that metaphor is not fair.

The characterization also didn’t make sense to Davidow. “There’s been a negative focus on adolescents as poor decision-makers,” she says. She wondered if their focus on rewards might actually help teens learn from important experiences. For instance, might it help if them remember good experiences more easily than other age groups? If it did, that might be valuable for gaining information that would prove important later in life.

Peering into the teenage brain

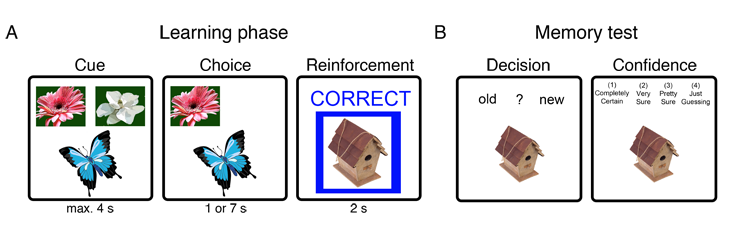

To find out how teen memories compared to adults, Davidow and her colleagues recruited 41 teens, ages 13 to 17, for tests. Fourteen were girls. They also recruited 31 adults, ages 20 to 30 (18 were women). All were presented with choices on a computer of two flowers and a butterfly. Each person had to guess which type of flower the butterfly liked best. When they got it right, “correct” would flash across the screen. Make a mistake and the computer would report they were “incorrect.”

Accompanying each answer would be a picture of something completely pointless. It might be a birdhouse, for instance, or a hammer. These pictures were not connected to the test. They were just randomly presented along with the “correct” or “incorrect.”

Story continues below image.

Then it was on to the next butterfly and pair of flowers.

Such a test is known as a reinforcement learning task. That means the test-takers first get reinforcement from learning if their answer had been right or wrong. They then learned from that to make the right choices later when they again saw that same pairings of butterfly and flower.

But in this case, the scientists also gave the participants a different memory test. A computer showed each person the seemingly irrelevant objects that it earlier had flashed up during the “correct” or “incorrect” judgements. The test then asked if the test-taker had seen the objects before, and how confident they were that they had.

Both teens and adults remembered the objects better when they had gotten questions about the pairings right than when they had erred. But teens mastered this faster than adults did. They also remembered the irrelevant items — the birdhouses and hammers — better when they were surprised by their feedback. Maybe they expected to get something wrong but got it right. When they did, the teens developed a stronger memory than the adults had.

Davidow and her colleagues placed 25 of the teens and 22 of the adults into an fMRI scanner as those recruits played the game. This machine uses strong magnets to measure the blood flow in a body part. The researchers scanned the test-takers’ brains as they were given the memory test. An increase of blood flow would point to those areas at work during the task.

Here, Davidow was especially interested in looking for where brain activity rose (or fell) at the same time in different regions during these tasks. When blood flow rises at the same time in two areas for the same task, she explains, “it suggests they are working together to get the thing done.”

Davidow focused on the striatum (or reward center) and hippocampus, which is involved in learning and memory. In teens who learned better, both regions lit up on the scans at the same time. That indicated their activity was connected.

The striatum was more sensitive in teens than in adults’ to the test’s reinforcement — their learning from a right or wrong answer. While this was happening, their hippocampuses were taking note.

Davidow and her colleagues published their results in Neuron on October 5.

This paper “provides a really nice suggestion for what may be the possible benefits for the increase in reward sensitivity during adolescence,” says Noa Ofen. She’s a psychologist at Wayne State University in Detroit, Mich. What the teens remembered — random birdhouses and hammers — weren’t part of their original task, she notes. It is therefore not clear if the right and wrong responses cemented those images, or if it was something else. “So whether one successfully encodes them or not is not the result of learning through reinforcement,” she challenges. It’s more a byproduct of the task. And even if teens did remember that random information better, she asks, would that truly be useful?

Ofen hopes that more studies will look at precisely how laying down new memories differs in teens and adults.

It would be nice to see just how teen-specific this effect is, says Casey at Yale. But it’s also good to see the teenage brain studied as a stage in development, looking at both pros and cons. It’s more useful than merely characterizing it as a brain run amok.

“I love this kind of work,” she says. “It’s great to show who teens are and what they can do.” And it’s also good to show that the development quirks in the teen brain that give adults fits might have an upside after all.