These teens are using science to make the world a better place

Middle-school scientists are tackling global issues from litter cleanup to period poverty

Several finalists in the 2023 Thermo Fisher Scientific Junior Innovators Challenge have done research projects that aim to make the world a better place.

Society for Science

For some, a science project might be an assignment. For others, it might be a fun hobby. But doing research can also be a chance to help others and make the world a better place. Just look at some of the projects done by teen scientists in this year’s Thermo Fisher Scientific Junior Innovators Challenge (JIC).

The Thermo Fisher JIC is a science competition for U.S. middle-school students. It’s run by Society for Science, which also publishes Science News Explores. The 30 finalists in this year’s competition traveled to Washington, D.C., this week to compete for more than $100,000 in prizes. They also showed off their research projects.

These middle-school scientists are tackling global problems from litter pollution to period poverty. Science News Explores spoke to three of them about their inspiration, excitement and future plans for their projects.

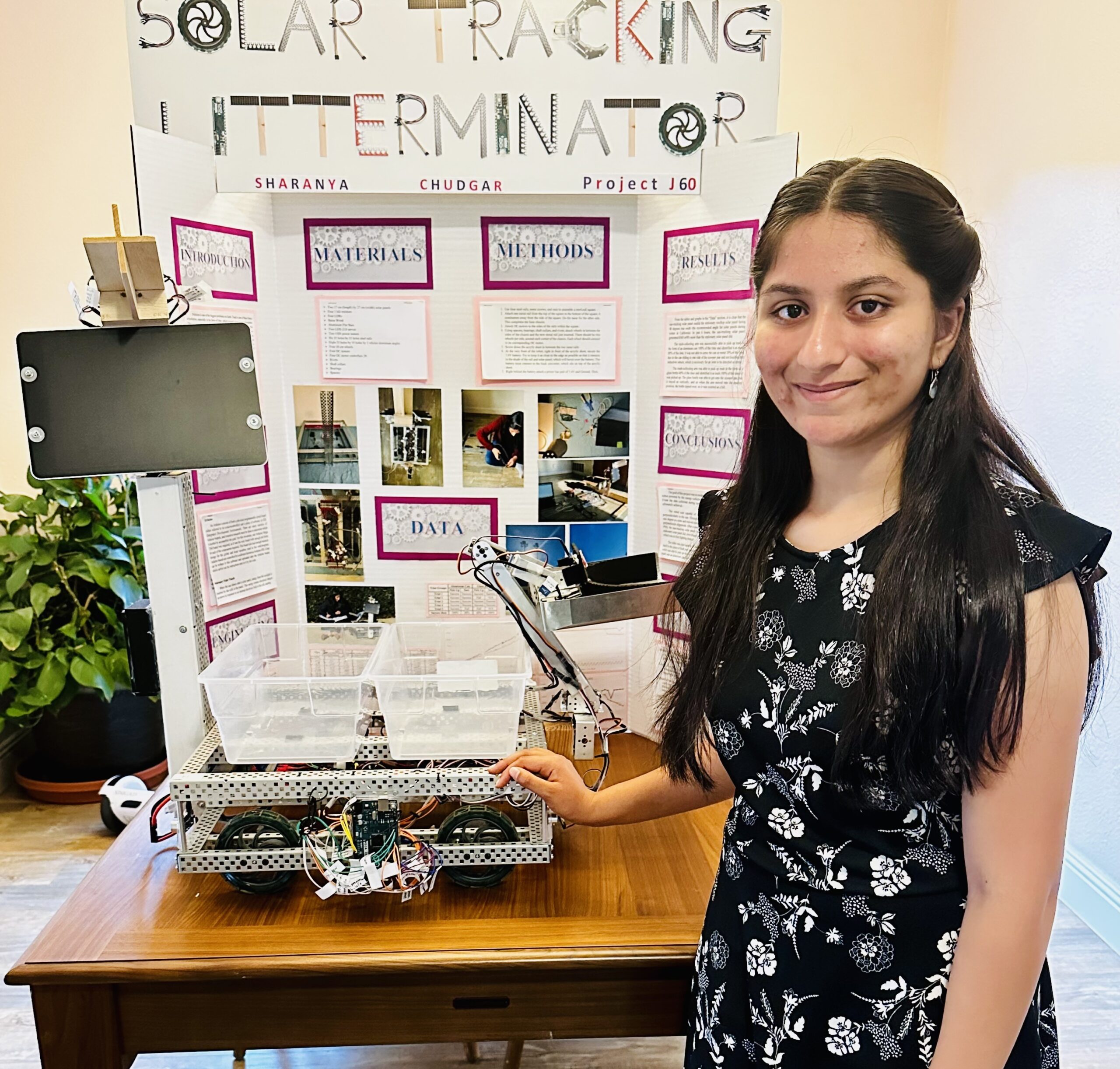

Sharanya Chudgar

Sharanya, 14, built a solar-powered trash-collecting robot. The wheeled machine uses sensors to spot litter and a pan to scoop it up. The robot’s metal-detecting sensor helps it sort garbage from recyclables. And a light sensor lets the robot’s solar panel angle itself toward the sun, collecting as much energy as possible. Sharanya is an eighth grader at Challenger School–Shawnee in San Jose, Calif.

What inspired this project?

“When I signed up to volunteer at our local trash cleanup, I saw how much litter pollution there was, and I knew that I had to fix this problem,” Sharanya says. “People do have very limited time and resources, right? But robots don’t. So it was then that my project idea formed in my head.”

What was your favorite part of this project?

“Building the robot,” Sharanya says. “Ever since first or second grade, I’ve loved building Legos, and building my robot felt just like building a Lego. Except this time, I had to come up with the instruction manual … I haven’t ever had any experience in robotics before, so it was a completely new experience.”

What resources helped you complete your project?

“My father. Throughout the project, I’ve had to use tons of power tools, and I even had to cut pieces of metal to certain lengths,” Sharanya says. “Whenever I had to use a power tool, my dad was always there to supervise and help out if necessary. … He’d also always come to the rescue whenever I accidentally burned a [piece] or melted a wire.”

Any advice for science project newbies?

“Follow the scientific method. It might seem difficult at times, but sticking to this and changing just one variable at a time gets you the best results,” Sharanya says. “And honestly, don’t be afraid of making mistakes. Everyone’s afraid. ‘Oh no, what if I mess this up?’ To be quite honest, making mistakes is a part of the whole learning process. So don’t be afraid.”

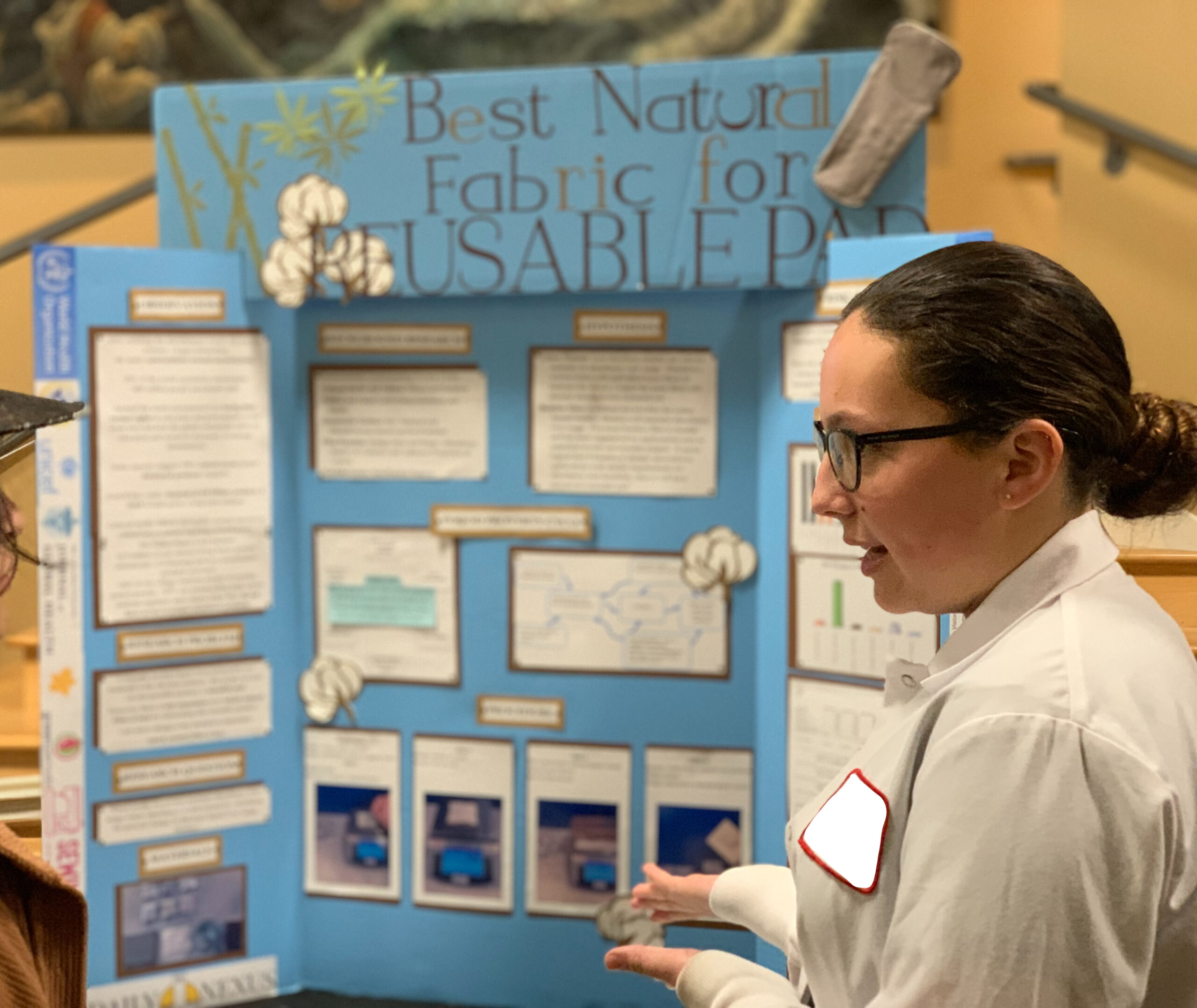

Ellie Lou Olvera

Ellie Lou, 13, wanted to help solve the global problem of period poverty. This is a lack of access to menstrual products, ways to hygienically use them or education about how to use them. In fact, surveys suggest that more than half of people with periods worldwide don’t have access to proper menstrual products. Ellie Lou studied which natural fibers work best for making affordable, reusable menstrual pads. Her work showed that fabrics made with cotton and hemp were most absorbent. Ellie Lou is in the seventh grade at Santa Barbara Charter School HomeBased Partnership in Goleta, Calif.

What inspired this project?

“Periods are a big topic for conversation in a 12-year-old girl’s life,” Ellie Lou says. “And my family and I, we love to research. So we were doing our own research together, and we discovered this documentary.” The film was Period. End of Sentence. “There, the words ‘period poverty’ were mentioned,” Ellie Lou says. “I thought, what can I, a 12-year-old girl, do to help?” She decided to sew menstrual pads and donate them to people in need. “When I went to research which natural fabrics I could use to sew these pads, I discovered that there was not a consensus as to which natural fabric was best.”

Did you encounter any unexpected obstacles?

“When I was pitching my idea to a group of peers, one of my classmates asked, ‘Is menstruation a disease?’” Ellie Lou says. “That’s when I realized that I had a lot of work ahead of me, because … it was my duty to make sure that people knew what menstruation was. Because if they did not understand menstruation, how would they understand period poverty? And if they couldn’t understand period poverty, how would they be able to put my project into context? So I had to make sure that when I presented, I was making everybody feel comfortable to talk about the subject matter and also to ask questions so that they could learn more.”

What was your favorite part of this project?

“I loved my testing, because each fabric reacted so differently,” Ellie Lou says. “Even if it was the same exact material just woven or put together in a different way, it had a crazy different reaction.” She was especially surprised to find that pads made from reused fabrics were more absorbent than new fabrics. “Which was a huge discovery,” Ellie Lou says, “because of the amount of surplus fabrics we have in our waste streams that could be redirected into solving a humanitarian crisis.”

What most excites you about this project?

“I discovered in my project that we can do so much to help bring change,” Ellie Lou says. “Every person can help simply by using common household items, like old towels or old t-shirts, and sewing their own pads, both for their use and for other people’s use. And that this crisis, unlike so many others, is easy to solve… It doesn’t cost millions of dollars or need new science to be invented.” Even people who don’t want to sew pads can help, Ellie Lou adds. “Some people like to donate supplies,” she says. “Together, we can help to defeat period poverty.”

Amritha Praveen

Amritha, 14, built a system that uses people’s responses to music to recommend songs that put them at ease. Her goal? To improve the effectiveness of music therapy for mental health. Amritha’s system uses sensors to measure someone’s heart rate and sweat while listening to music. Then, the system uses that information to recommend other music that is likely to help the person relax. Amritha is in the eighth grade at Aptakisic Junior High School in Buffalo Grove, Ill.

What inspired this project?

“I’ve been a musician for more than half of my life,” says Amritha. She currently plays the viola and the veena, a string instrument that originates from India. “They’re both very different. They’re very different genres and styles. When I play the instruments and when others around me are listening to me playing these instruments, they all face different emotions and relaxation. So that’s kind of where I got the idea to start this project to find an objective way to measure the relaxation when listening to different types of music.”

What was your favorite part of this project?

“Finding out what musical features impacted our emotions the most and our relaxation the most,” Amritha says. “That was one of my favorite parts, because it was something that I was really curious about.” She found that musical key played a role in music’s relaxation potential. “That’s something there’s been a lot of research about,” Amritha says. “I also found that timbre was relaxing, which I didn’t expect.” Timbre is the tone or color of the music.

What’s next for you?

“I am interested in continuing to work with this project, because there’s still a lot that I’ve left to uncover,” Amritha says. “I’d also like to see if different types of instruments could also influence our physiological responses.” And she’d like to use EEG brain waves, in addition to heart rate and sweat, to track how people respond to music. “I think that that could also give a lot of insight into why we feel this way when we’re listening to these types of music,” Amritha says. “Because obviously it has a lot to do with the brain.”

And the winners are…

Ellie Lou was among the top winners of this year’s Thermo Fisher JIC. She took home the $10,000 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Award for Health Advancement.

Amritha won the second-place STEM Award for achievement in mathematics. She received $2,500 to put toward a STEM summer camp.

Shanya Gill took home the competition’s top prize: the $25,000 Thermo Fisher Scientific ASCEND Award. The 12-year-old from San Jose, Calif., developed an automated system to detect fire hazards when no one is home. Check out the full list of winners here.

Other $10,000 winners from this year’s competition included:

- Keshvee Sekhda, 14, of Sugar Hill, Ga., who co-developed a smartphone app to help identify breast, lung and skin cancer

- Maya Gandhi, 14, of Anaheim, Calif., who explored ways to boost the energy output of plant microbial fuel cells

- Adyant Bhavsar, 13, of San Jose, Calif., who created a low-cost, eco-friendly version of a triboelectric generator