The many efforts to lick cat allergies

Scientists seek to reduce people’s urge to sneeze

Up to 20 percent of people — one in every five — may be allergic to cats. But scientists are working on solutions so that these individuals can get their kitty cuddles.

Martin Poole/Getty Images Plus

Time magazine’s list of Best Inventions of 2006 included an unusual creation. It wasn’t a gadget; it was a cat.

“Love cats but your nose doesn’t?” the magazine asked. “A San Diego company is breeding felines that are naturally hypoallergenic.” (Hypoallergenic means that something is unlikely to cause an allergic response.) There was a 15-month waiting list for these “sniffleproof kitties,” which sold for $3,950 or more.

The company selling the cats was Allerca. It had tapped into a tantalizing dream for allergy-prone cat lovers. Just two genes are responsible for making cats a problem for many people. It therefore seemed like a no-brainer to engineer cats that lacked those genes — or to simply breed cats with versions of the genes that made the animals less allergenic.

But so far, itchy-eyed cat lovers have been left disappointed.

By 2010, Allerca had stopped taking orders. Lawsuits were lining up. The sniffle-proof kitties never materialized. Some angry customers said they never received a kitten. Others were sent a cat that set off their allergies.

But for all those who haven’t given up hope, there may be new options around the corner. An allergic owner might pop open a can of allergy-fighting food — for the cat. Or maybe vaccinate the cat to produce fewer allergens. And allergy shots for owners might shift from weekly or monthly injections to a shot that offers immediate relief.

The new gene-editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 might even come to the rescue. This technology might deliver the ultimate dream to those who can afford it: a cat that doesn’t produce allergens at all. One company has made some progress applying CRISPR/Cas9 to cats.

Success in taming cat allergies might even bring good news for people whose allergies have nothing to do with cats. If any of the cat allergy–fighting measures prove safe and effective, they might be deployed against other allergens. They could prove especially useful against airborne ones like pollen, dog dander or dust mites. Up to 30 percent of the world’s population suffers from allergens in the air. So that’s plenty of runny noses to dry up.

When it comes to cat allergies, the main culprit is Fel d1. This small protein is produced primarily in cats’ salivary and sebaceous glands. Fel d1 is found in flakes of dead skin, or dander. It is spread to hair when a cat licks itself. Thus it’s not cat hair that people are allergic to, just hair coated in cat spit.

A singular target

As allergens go, Fel d1 gets around. It sticks to hair and clothing, so it’s easily carried from place to place. It lasts for weeks or months before breaking down. It’s light and easily enters the air. That makes it even more insidious. In fact, even houses without a cat tend to have a little Fel d1 in their dust, says Martin Chapman. This immunologist is president and CEO of Indoor Biotechnologies. It’s a company in Charlottesville, Va., that tests for allergens and allergies.

All cats produce some amount of Fel d1. However, that doesn’t mean that all cats are equally allergenic. In tests of hundreds of cats, Indoor Biotechnologies found levels ranging from just 5 to as much as 2,000 micrograms of Fel d1 per gram of fur. Variations in two key genes explain much of that wide range. But no one knows exactly which versions of the genes result in low-allergen cats.

It’s also not clear what role Fel d1 plays in cats. Lions and other big cats have their own version of the protein, Chapman notes. So it seems to have stuck around during cat evolution. That suggests the protein does something. Male cats that haven’t been neutered tend to have the highest Fel d1 levels, which have been linked to male hormones. Based on that association and the protein’s similarity to other molecules, Fel d1 might be a pheromone. That’s a chemical used to communicate via scent. But no one knows whether the protein plays some role in keeping cats healthy.

All this uncertainty has made allergies to cats difficult to tackle. For now, options are limited. People can take antihistamines and other medications to reduce symptoms. But such drugs don’t stop the allergy.

Traditional allergy shots are known as immunotherapy or desensitization therapy. They aim to retrain a person’s immune system to be less sensitive to an allergen. But those shots are a commitment. A patient may need up to 100 injections over three to five years.

Some people can avoid needles by taking under-the-tongue daily drops of the same U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved allergens as in the injections. But this treatment often is not covered by insurance.

“Desensitization therapy has been the only therapy for decades,” says Gerald Nepom. He is director of the Immune Tolerance Network in Seattle, Wash. It’s a research group funded by the National Institutes of Health. Exactly how desensitization works is still not fully understood. But the basic idea is that exposing the immune system to small amounts of allergens causes the body to make antibodies that block part of the allergic response. Unfortunately, Nepom says, desensitization generally doesn’t eliminate all symptoms. And the effects aren’t always permanent.

Allergy treatments

There is no permanent cure for cat allergies, though a number of available treatments can reduce symptoms in many allergy sufferers. New treatments aim to do a better job at this or stop the allergy process in its tracks.

| TREATMENT | AVAILABLE NOW? | ACTION | PROS | CONS |

| Antihistamines | Yes | Block histamine production | Newer drugs like cetirizine (Zyrtec) and fexofenadine (Allegra) cause less drowsiness than previous drugs | May not eliminate symptoms |

| Nasal steroids | Yes | Reduce inflammation in the nose | Reduce sneezing, congestion and runny nose | Only treat symptoms |

| Traditional allergy shots or drops | Yes | Exact mechanism unknown; may increase helpful antibodies | The only current therapy that reverses some allergies | Requires many shots over several years |

| Allergy shots of lab-made antibody | No | Block immune system’s recognition of allergen | Fast-acting prevention of allergic response | Boosters required |

| Pet food with antibodies | No | Cuts amount of active Fel d1 allergen in cat saliva | No shots needed | Does not eliminate all Fel d1 |

| Vaccine for cats | No | Prevents human immune system from recognizing cat allergen | No shots needed for people | Does not eliminate all Fel d1; more testing needed to confirm safety for cats |

| Genetic engineering of cats | No | Removes genes that direct Fel d1 production in cats | With no Fel d1, nearly all cat allergies would be eliminated | Effects on cats are unknown |

Newer approaches are focusing on Fel d1. They either directly neutralize it or block its interaction with the human immune system. The competition to devise an effective solution to cat allergies is fierce. Because of the large potential market — about 10 percent (some estimate 20 percent) of people are allergic to cats — a successful approach could make companies a lot of money.

Applying lessons learned here to other allergies is a strong motivator, too.

Improving immunotherapy

One problem with traditional immunotherapy is that it tries to stop one of the later steps in the allergic response. Immunoglobulin E, or IgE, is an antibody that triggers an allergic reaction. Antibodies patrol the body looking for specific interlopers. In people with allergies, the IgE only latches onto the proteins or chemicals — allergens — that trigger their allergy.

When an IgE find its allergen, the antibody raises an alarm. It does that by telling certain cells that something is wrong. Those cells make chemicals called histamines (HIS-tuh-meens). It’s the job of histamines to get rid of bothersome things by any means necessary. Those histamine chemicals might make eyes water, or trigger coughing, sneezing or itching. That’s helpful when the substance poses harm. But it is not pleasant when the substance — like cat dander — is actually harmless. In allergies, this histamine response can go way too far. It can even cause people’s throats to swell shut and other life-threatening consequences.

Traditional immunotherapy blocks the histamine-producing part of this reaction. Yet that’s only one part of the body’s response to an allergen.

“We now see allergy as an immune-activation symphony,” explains Nepom. Rather than a strict chain of single events, it’s more like an orchestra. And it has many players (molecules) performing on cue.

Today, Nepom says, allergy researchers are getting a clearer understanding of the role of each player. “This is like figuring out which part of the orchestra is creating the problem. Is it the horn section or the strings? Or do you have a single oboe player going rogue?” Knowing that could help researchers target players in the immune system more efficiently, he says.

For example, one research group funded by the Immune Tolerance Network is wrapping up a human trial that goes by the name of CATNIP. This clinical trial is testing what’s called an “allergen-plus” approach. Scientists combine small amounts of Fel d1 with an antibody that blocks a substance important to triggering the allergic response. That substance is a protein that helps spark and maintain allergic reactions. It may be one of those rogue oboists. The idea is that if this treatment works, a patient would develop a long-lasting tolerance from a one-year series of allergy shots. That may sound like a lot, but today’s version of such a therapy requires three to five years of shots.

Other parts of the allergic response are prime targets, too, says Jamie Orengo. She is an immunologist at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals in Tarrytown, N.Y. (Regeneron is a major financial supporter of the Society for Science & the Public. The Society publishes Science News for Students.)

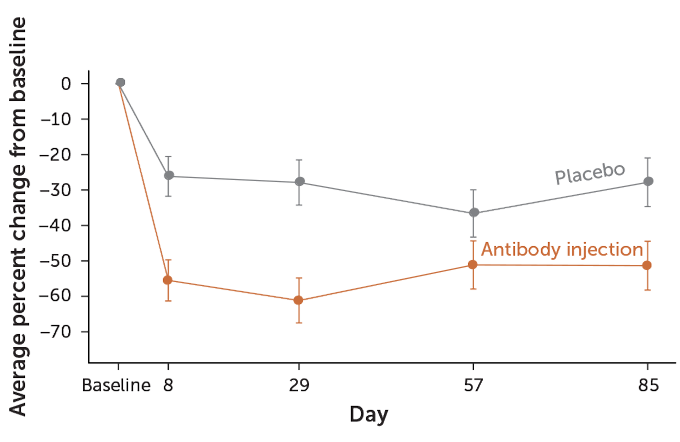

SOURCE: J.M. Orengo et al/Nature Communications 2018 T. Tibbitts

The company has designed antibodies that are highly specific to Fel d1. These antibodies bind to and lock up the allergen before the immune system can react to it. It’s an amped-up version of traditional immunotherapy. And it’s one that could be used to target other allergens, Orengo notes.

“We don’t have to rely on the human body. We can make those antibodies in the laboratory instead of waiting for them to be generated by the person naturally,” Orengo says. Tests in mice and in people allergic to cats showed fewer allergy symptoms after just one treatment, her team reported in a 2018 paper in Nature Communications. That one treatment gave results that used to be seen only after years of conventional immunotherapy. Most people treated saw as much as a 60 percent reduction in nasal symptoms.

One shortcoming: While this approach is very fast-acting, it doesn’t retrain the person’s immune system. Someone receiving the treatment would need periodic boosters — perhaps every few months.

Special cat food

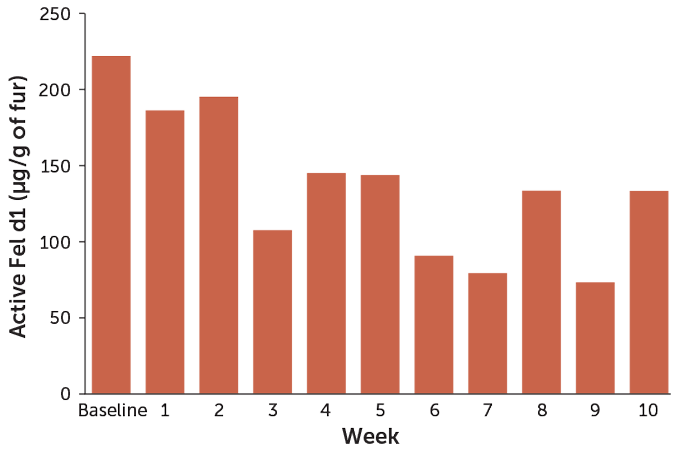

Cat saliva is the biggest source of Fel d1. Researchers at Nestlé Purina are now testing cat food containing an antibody. It binds to the protein in saliva as a cat eats. This antibody doesn’t prevent the cat from producing the allergen. It does, however, make it almost impossible for the human immune system to recognize the allergen.

“In fact, this was an important strategy behind our research,” says Ebenezer Satyaraj. This immunologist is leading the research at the Purina Institute in St. Louis, Mo. “We didn’t want to stop the production of Fel d1 because currently it is not clear what role it has in the cat.”

SOURCE: E. Satyaraj et al/Immun., Inflamm. and Disease 2019T. Tibbitts

Tests so far suggest that the food can knock down the amount of active allergen on cat hair by about half. That may be enough to offer relief to some people with mild to moderate cat allergies. The company expects to begin selling the cat food later this year.

But it won’t help everyone. People with severe allergies or asthma may be unable to tolerate any amount of Fel d1 without causing symptoms, says Michael Blaiss. He is executive medical director of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology in Augusta, Ga.

Vaccinate the cat

There are cat lovers out there who’d probably be happier letting the cat get the shots. So another new approach aims to vaccinate cats against their own Fel d1. The shot would stimulate a cat’s immune system to produce antibodies that bind to Fel d1. That should make it so that human immune cells no longer recognize — and react — to the protein.

Researchers at HypoPet AG in Zurich, Switzerland, studded an inactive fragment of a virus with dozens of Fel d1 molecules. “If you make the allergen look like a virus, the immune system thinks it is a virus,” says Martin Bachmann. He is chief scientific officer of HypoPet. He’s also an immunologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland. This “Trojan horse” then triggers the cat’s immune system to start seeing Fel d1 — which it normally ignores — as an invader.

An initial test was done in more than 50 cats. Three injections of the vaccine were given three weeks apart. They stimulated the cats to make antibodies specific to the allergen. This reduced the cats’ secretion of the protein by more than half. And it did this without harming the cats, the researchers reported last July in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. The company now plans further safety testing, Bachmann says. HypoPet is working with U.S. and European Union regulators to bring the vaccine to market.

The hypoallergenic cat

Producing a cat that makes no allergens at all is still the goal for some researchers. The fact that some cats are naturally low in Fel d1 suggests that such pets could be bred. This is what Allerca tried and failed to do a decade ago. But frustratingly, you can’t just breed two cats with low Fel d1 levels and get a litterful of hypoallergenic kittens.

Oregon cat breeder Tom Lundberg has bred Siberian cats for more than 10 years. His goal has been to breed low-allergen cats. Lundberg himself is allergic to cats. He became fascinated by Siberians after owning one to which he was not allergic. But a second one, he recalls, gave him a “snotty nose and itchy eyes.”

Lundberg has long measured his cats’ allergen levels and tracked the results of breeding. He can confirm that there’s no way to guarantee that all the kittens in a litter will hit the genetic jackpot. He and his wife, Meredith, now sell the cats they breed based on their Fel d1 levels. Those tested with the lowest levels, which are the most rare, command the highest prices. These cost up to $5,200 for a kitten in the “extremely low” range of less than 1 microgram of Fel d1 per gram of fur. Only about 1 in 15 of the kittens he breeds from low-allergen cats fall into that category, he says.

Lundberg has received hundreds of calls from people giving up Siberian cats that breeders had claimed were hypoallergenic. “They’ll say the kittens were ‘bred from hypoallergenic lines,’” he says. “That’s like saying corn was bred from corn — it’s meaningless.”

Anyone interested in buying a low-allergen cat, he says, should insist on seeing test data. He also notes that buyers with severe allergies may not be able to tolerate any amount of Fel d1.

Indoor Biotechnologies is trying to genetically engineer a cat that makes no Fel d1. “We’re working on it,” says Chapman, who founded the company. This company has used CRISPR/Cas9 to delete two genes. The company has filed for a patent on the process. Called Ch1 and Ch2, the genes being deleted would have instructed cells on how to make Fel d1. So far, the gene edits have worked for cat cells growing in cell-culture dishes.

Next, the company will try knocking out these genes in cat salivary tissues, also growing in a lab dish. Researchers will then make sure Fel d1 is no longer being made, says Nicole Brackett. She’s a postdoctoral scientist at the company. She has analyzed the DNA sequence of the Ch1 and Ch2 genes of 50 cats. She now has plans to do the same for 200 more cats. That will help identify the best gene region to target using CRISPR/Cas9.

If the genetic trick works, engineered cats would lack part or all of the genes needed to make Fel d1. Some cats naturally produce very little of this with no ill effects. So the thinking is that preventing cats from making the protein is unlikely to harm them. But scientists won’t know for sure until someone tries it. “That’s precisely the reason to do the experiment,” Chapman says.

Typically, producing such a cat would require deleting the gene from an embryo. The embryo would then be implanted in a female cat until the kitten is born. But Chapman doesn’t want to get into the breeding business. Instead, he hopes to ultimately edit the genes of adult cats. That is similar to gene therapies being developed now for people (which use a harmless virus to deliver gene-editing tools). Recent experiments have successfully edited the genes of adult mice and even people with sickle-cell disease, for instance.

Such a virus could be delivered by having a veterinarian inject it into the cat’s salivary glands. Or it might come as skin treatment to reach the sebaceous glands in the skin. And if it edits the genes for Fel d1, “that would be exciting,” Chapman says.

One researcher working to wipe out cat allergies won’t be standing in line for any injections, however. Bachmann, of HypoPet, says that he and his son are allergic to cats. When asked if he would try any of the new allergy treatments, he replied no. “I don’t love cats that much,” he says. “I’m more a dog person.”

A personal quest

I’ve always been a cat person. So when I married Jay, who’s allergic to cats, among other things, I had a problem. Whenever Jay spent time around a cat, his eyes would start to itch. His nose would run.

But Jay loves cats, too. Like many allergy sufferers, he tried all the usual treatments. For a couple of years, he got monthly allergy shots. He now uses daily nasal steroids and the antihistamine cetirizine. Eventually, his allergies didn’t seem so bad. So we wondered if he could tolerate a cat. I’d been seeing a lot of claims about hypoallergenic cat breeds. I was skeptical but curious.

We’re both biologists by training, so we dove into the scientific literature. We didn’t find much. One small study in Veterinary Sciences from 2017 reported on mutations in Siberian cats that could potentially lower their Fel d1 levels or render the protein less allergenic. It was the barest of hints. But we decided to visit a Siberian cat breeder in Georgia and see if we might luck out.

That day we brought home Stoli on a trial basis. Stoli is a nearly 17-pound sweetheart. Jay’s allergic reaction to him was occasional and mild. And over a few months the sniffling seemed to diminish even more. We thought we’d found our low Fel d1 cat!

Then in the course of reporting this story, I decided to test Stoli. I sent off a fur sample to Indoor Biotechnologies. The result: Stoli’s fur tested at 790 micrograms per gram of fur — pretty darn high.

Maybe the immunotherapy that Jay has endured over the years gets more credit than Stoli’s genes. It’s OK. Despite those test results, we are definitely keeping the cat.— Erika Engelhaupt