This dinosaur was no bigger than a hummingbird

A skull from one of these ancient birds was found encased in a chunk of amber

This hummingbird-sized predatory bird is the smallest known dinosaur to live during the Age of Dinosaurs. That’s the Mesozoic Era, which lasted from 252 million to 66 million years ago.

Han Zhixin

Editor’s note: On July 22, 2020, Nature retracted the study described in this article. It was done at the request of the paper’s authors. In the retraction, the authors say: “Although the description of Oculudentavis khaungraae remains accurate, a new unpublished specimen casts doubts upon our hypothesis” — which had claimed it was a dino. A recent study posted at bioRxiv.org (a preprint server for studies that have yet to be peer-reviewed), examined the skull of Oculudentavis. That newer study suggests it was not a dinosaur, but a lizard. Jingmai O’Connor is one of the retracted study’s authors. In an e-mail to Science News, she notes that the unpublished specimen mentioned in the retraction strongly resembles Oculudentavis. That specimen had been analyzed by a different team of scientists. O’Connor now concedes Oculudentavis, too, was probably a lizard, albeit “a really weird animal.” And, she claims, it still is “an important discovery, regardless of whether it’s a weird bird or a weird lizard with a bird head.”

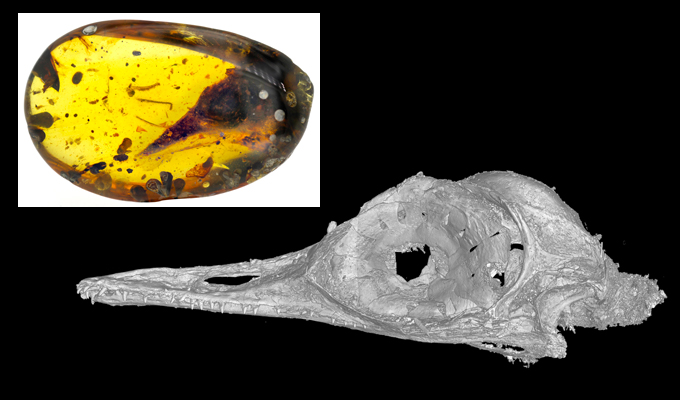

A tiny, toothed bird that lived 99 million years ago appears to be the smallest known dinosaur from the Mesozoic Era. That era lasted from about 252 million to 66 million years ago. The creature’s skull was 12-millimeters (a half inch) long. It had been encased in a chunk of amber. That chunk was originally discovered in northern Myanmar in southeast Asia. Researchers reported the find March 11 in Nature.

Modern birds are the only dinosaurs still living today. The bee hummingbird is the smallest of those. The newfound species was about the same size. It’s been named Oculudentavis khaungraae. Researchers made 3-D images of its fossilized skull with computed tomography. That’s a type of X-ray imaging. Those scans revealed that the Mesozoic bird had little but size in common with today’s nectar-sipping hummingbirds.

The images reveal a surprising number of teeth. That suggests the tiny bird was a predator, the researchers report. “It had more teeth than any other Mesozoic bird, regardless of size,” says Jingmai O’Connor. She’s a paleontologist. She works at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China. As for its prey, researchers can only guess, she says. O. khaungraae probably dined on arthropods and other invertebrates. It may even have eaten small fish.

The ancient bird’s had deep, conical eye sockets. They are similar to those of modern predatory birds such as owls. Those deep sockets can increase the eye’s visual ability without increasing its diameter. This suggests the ancient birds had sharp eyesight, O’Connor says. Owls’ eyes face forward, increasing their depth perception. But the eyes of the tiny dino faced out to the sides.

Some species evolve smaller adult body sizes over time. This is known as evolutionary miniaturization. There are limits to how small an animal can get. “You have all these restrictions related to trying to fit sensory organs into a small body,” O’Connor says.

She considered the possibility that this ancient bird had undergone such a miniaturization. When she did, “a lot of really weird, inexplicable things about the specimen suddenly made sense,” she says. The bird has several oddities. They include strangely fused teeth and a pattern of fusion in its skull. These “can be explained by miniaturization,” she says.

The small size might also be related to island dwarfism. That’s when larger animals evolve to smaller body sizes over many generations. This can happen because their ranges are quite limited, such as when they are confined to an island. The researchers aren’t sure exactly where the chunk of amber containing the bird skull came from. But anecdotal evidence suggests it may have come from a region in Myanmar that millions of years ago was part of an island chain.

Although it’s just one fossil, the find can shed light on how its body evolved to such a small size, says Roger Benson. He’s also a paleontologist. He works at the University of Oxford in England. He wrote a separate commentary about the discovery. It was published in the same issue of Nature.

The earliest birds, such as Archaeopteryx, arose around 150 million years ago. This find suggests that the body size of birds were reaching their lower limit by 99 million years ago, he says.

Scientists still need to figure out where the new species belongs on the tree of life. And that’s difficult, given the bird’s bizarre features, O’Connor says. “It’s just a skull. There’s a lot you can’t say,” she says. “Who knows what new [fossils] might tell us.”

About this story

Why are we doing this story?

This is a unique and important fossil of a tiny predator. And it’s a possible example of evolutionary miniaturization. In its way, this dino is a great ambassador for science. To start, it’s the type of find that is instantly compelling. It joins a dizzying array of recent fossil treasures found in amber from Myanmar. Each one is a reminder of the amazing diversity of life.

What questions didn’t the story address?

I didn’t discuss an important ethical debate. It is one now swirling around amber fossils from Myanmar. Profits from the amber mined in Myanmar’s conflict-ridden Kachin State may be helping to fund warring groups in the region. That may be leading to human-rights abuses. Science wrote about this in May 2019. As a result of these and other ethical concerns, some scientists have begun calling for a halt to scientific papers that describe fossils in Myanmar amber. Others, however, note the value of these specimens to science. By participating in the amber trade, some researchers say, scientists may be able to keep them from vanishing into private collections and being lost to the public trust. — Carolyn Gramling

What’s this box? Learn more about it and our Transparency Project here. Can you help us by answering a few brief questions?