This scientist wants to know how racial discrimination gets ‘under the skin’

Leticia Márquez-Magaña studies how stress affects the health of marginalized groups

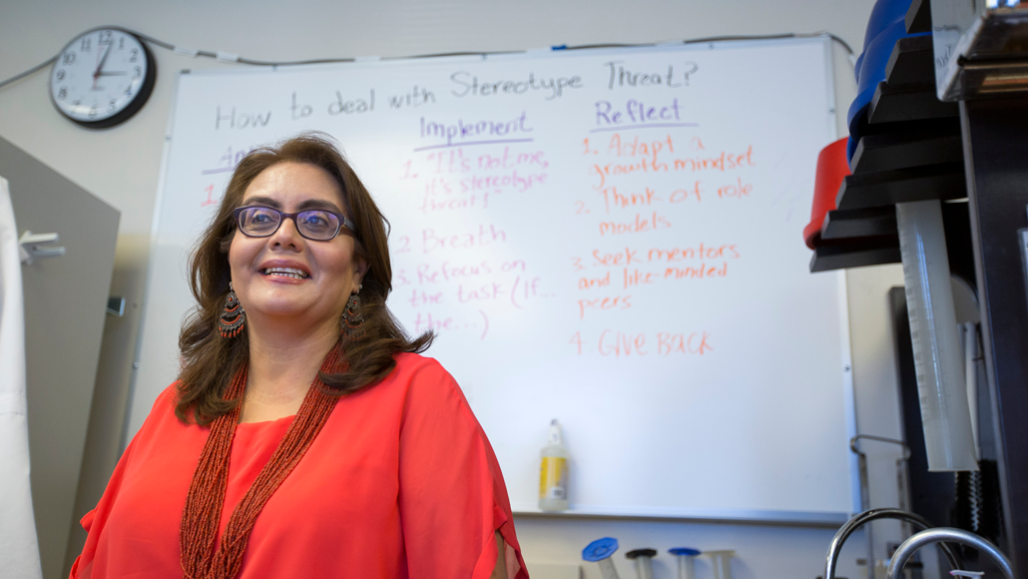

Leticia Márquez-Magaña studies the biological impacts of racism on African-Americans, Latina women and other marginalized communities.

San Francisco State University

When Leticia Márquez-Magaña was in high school, she knew she wanted to be a scientist. She got good grades, but some school staff said she shouldn’t aim so high. People like her shouldn’t be scientists, they said. Soon, however, she would prove them wrong.

Today, Márquez-Magaña is a cellular and molecular biologist. She directs the Health Equity Research Laboratory at San Francisco State University in California. Her team collects saliva, blood and hair. They analyze these specimens to investigate the biological impacts of racism and other experiences on marginalized communities, such as African-American and Latina women. Her group has explored, for instance, how the pressure to act like a “superwoman” — including the need to appear strong and motivated to succeed — impacts the health of African-American women in good and bad ways. And in another recent study, the team collected specimens and recruited research participants from a group that has worse health outcomes yet is often left out of medical research. Here it was rural Latina survivors of breast cancer.

In addition, Márquez-Magaña and her coworkers are collecting data on “microaggressions.” These are the subtle snubs or insults experienced in the everyday lives of underrepresented people, including students. Her team also is studying countermeasures to those snubs and insults. These small gestures are known as “microaffirmations.” And they can make someone feel valued and appreciated. Márquez-Magaña and her coworkers are tracking such moments to learn how to make science classrooms and labs more welcoming and inclusive to all students.

In this interview, Márquez-Magaña shares her experiences and advice with Science News for Students. (This interview has been edited for content and readability.)

What inspired you to pursue your career?

I’m a kid of Mexican immigrants. My siblings and I were not allowed to leave the home while my parents were working, which was all the time. So we watched a lot of TV. When I was in elementary school, there were only three channels — and lots of cartoons. In one episode, Bugs Bunny had on a lab coat. He was running around with a graduated cylinder full of green fluid that was bubbling over, and it just looked like he had so much fun. He dumped the contents onto a hairy monster, and the monster’s hair grew and looked beautiful.

From this, I got the idea that scientists have a lot of fun. In retrospect, I realized they also have the power to change things. Those two things inspired me to pursue science.

How did you get where you are today?

I learned a lot about American society from watching TV. One time on The Brady Bunch, they were talking about applying to Harvard University. I could tell Harvard was a big deal, that it was a status thing. And then, separately, I heard that Stanford University was “the Harvard of the West.” I figured Harvard was a chain, like Taco Bell and McDonald’s. I said, “I’m going to apply to the ‘Harvard of the West.’” I actually didn’t know that Stanford was its own thing until I was on the campus for freshman orientation.

Getting to Stanford wasn’t simple. There were advisors and teachers who tried to derail me. They were well-intentioned and said they wanted my best — but they believed that my best was becoming a secretary. For them, becoming a scientist was something completely out of my reach. They would say, “What do you mean you’re applying to Stanford? You’re not going to get in.”

But then there was Mrs. Hawkeswood. She was my history teacher. And she would say, “Leti, you can get in. You’re the best student in the school.”

For all four years of high school, I was the top student. I was thinking, I’m a shoo-in for valedictorian. But when I applied, I was told, “Why are you applying for valedictorian? You speak Spanish. You should be the Spanish salutatorian.” And I thought, yes, I do speak Spanish, but I was also the top student all four years. I’m a National Merit Scholar.

And I got into Stanford.

In the end, the school had co-valedictorians for the first time ever — because they couldn’t just have a Latina be the valedictorian. I realized early on that I need to be careful who I trusted with my dreams.

How do you get your best ideas?

By not focusing on them. By not focusing on the question I want to answer — the problem I want to solve — the answer eventually comes to me.

I think that’s the opposite of what you’d expect. But what I find is that I’ll do all this hard thinking and I’m just stuck. And then I’ll go do some laundry or take a shower and part of my mind works on it. Research shows that engaging in something that takes your mind away from your block point helps you come back to it renewed, refreshed, with a better idea. That’s why Google, Apple and a lot of biotech companies have game rooms.

What’s one of your biggest failures, and how did you get past that?

When I became a scientist, I wanted to change things, to improve human health and well-being and diminish human suffering. But when I went to Stanford, I was told that pure science was politically neutral. I was told to stay away from research motivated by social issues because it was tainted. And so I started with microbial genetics — studying a little bacterium and the machinery that governed whether it went in one direction or another.

But I wasn’t true to myself. I didn’t follow my heart. I followed what people were telling me to do. I felt like I was conned. I let myself be conned. So that’s a failure.

But that didn’t last. I moved to a field that felt more true to myself.

What’s one of your biggest successes?

I think one of my biggest successes was getting out of microbial genetics. This kind of basic science research is often done by individuals who don’t share data or work with others. But it’s well-respected by other scientists. Instead, I moved into the field of health equity research. This type of science aims to collect evidence for health differences that are driven largely by social, economic and environmental factors. The work is often conducted by a team of researchers with different specialties. It usually engages the community. So the research is more impactful and meaningful — even though it has less prestige.

What do you do in your spare time?

I hang out with my family. I love my family and I cook for them. I’m not in the lab but I follow a protocol (aka a recipe), modify it as needed — and, based on the results, conclude whether it was worth it.

For New Year’s Eve, I made beef Wellington. (That’s a fancy dish that involves beef covered in puff pastry.) I enjoy doing that sort of thing with my family. We also go bowling. We play mini-golf. The other day we went to see a movie. I have two sons, ages 23 and 26. The 26-year old has a girlfriend. We go out regularly on group dates. How cool is that?

What piece of advice do you wish you had been given when you were younger?

Learn from your ancestors.

American history is not inclusive of all ancestral heritages. My ancestors are European, specifically Spanish, and I learned some about that — you know, the Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria that brought Christopher Columbus across the Atlantic.

But I didn’t learn about the amazingness of my indigenous ancestors, the Aztecas. They were the premier applied mathematicians of their time. While the bubonic plaque swept through Europe, people were basically throwing poo out the window because there was no sewage system. But in Mexico there were aqueducts and sewage systems.

If I had learned earlier that my Aztec ancestors were premier mathematicians and applied scientists, I think it would have gone a long way to combat some of the negative messaging I got that said I wouldn’t be able to do science.

This Q&A is part of a series exploring the many paths to a career in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). It has been made possible with generous support from Arconic Foundation.