acoustic: Having to do with sound or hearing.

bat: A type of winged mammal comprising more than 1,400 separate species — or one in every four known species of mammal. (in sports) The usually wooden piece of athletic equipment that a player uses to forcefully swat at a ball. (v.) Or the act of swinging a machine-tooled stick or flat bat with hopes of hitting a ball.

beetle: An order of insects known as Coleoptera, containing at least 350,000 different species. Adults tend to have hard and/or horn-like “forewings” which covers the wings used for flight.

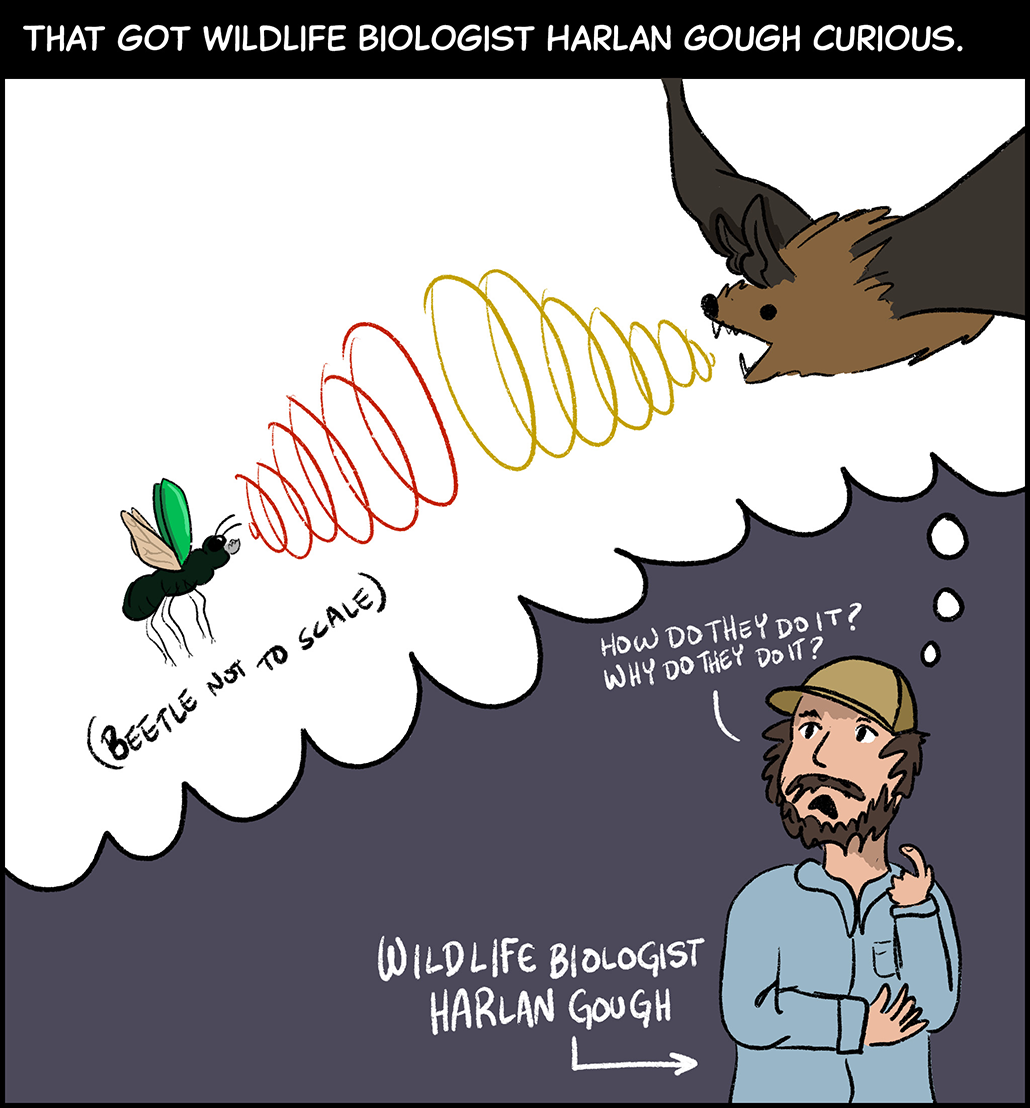

biologist: A scientist involved in the study of living things.

chemical: A substance formed from two or more atoms that unite (bond) in a fixed proportion and structure. For example, water is a chemical made when two hydrogen atoms bond to one oxygen atom. Its chemical formula is H2O. Chemical also can be an adjective to describe properties of materials that are the result of various reactions between different compounds.

colleague: Someone who works with another; a co-worker or team member.

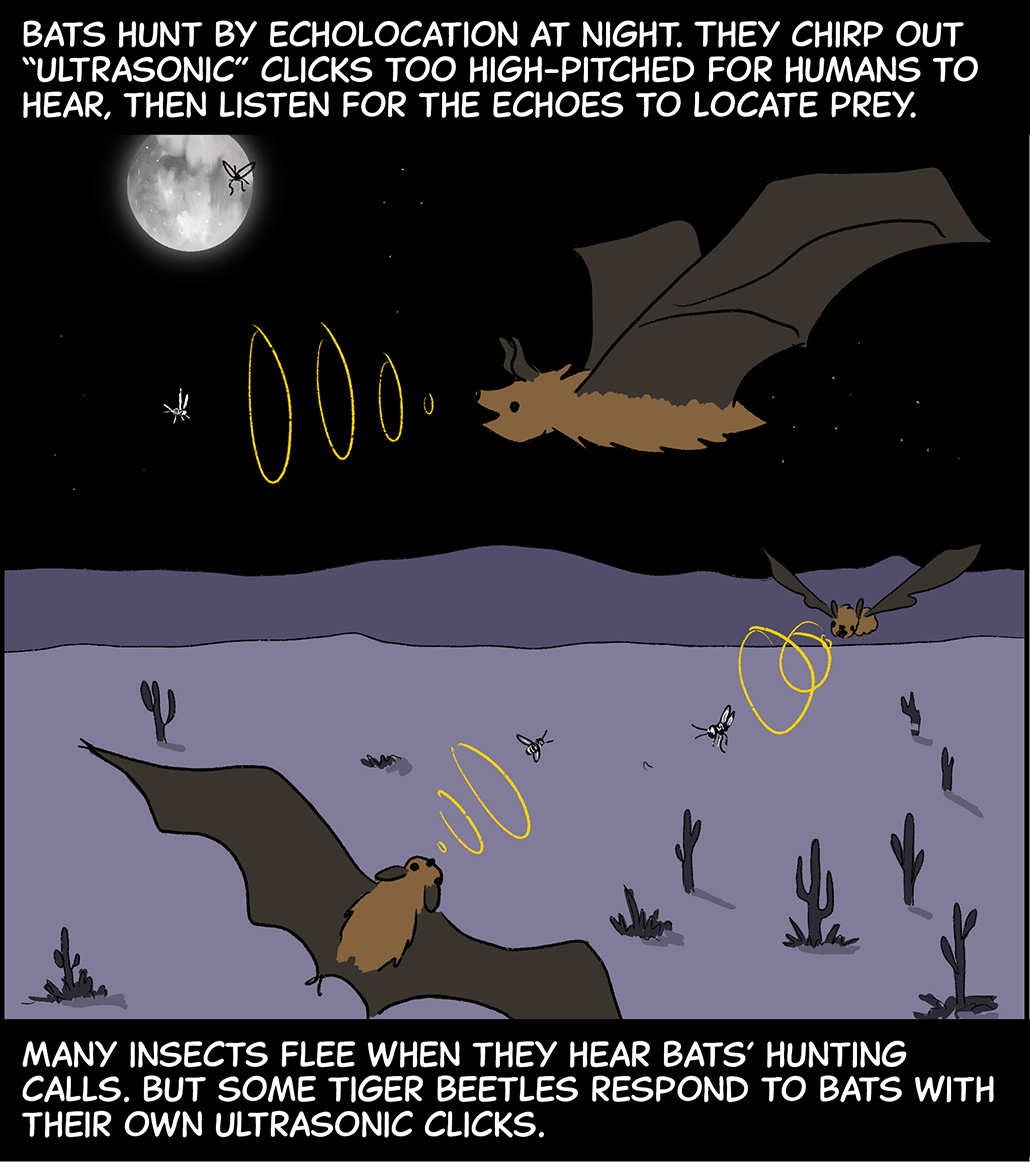

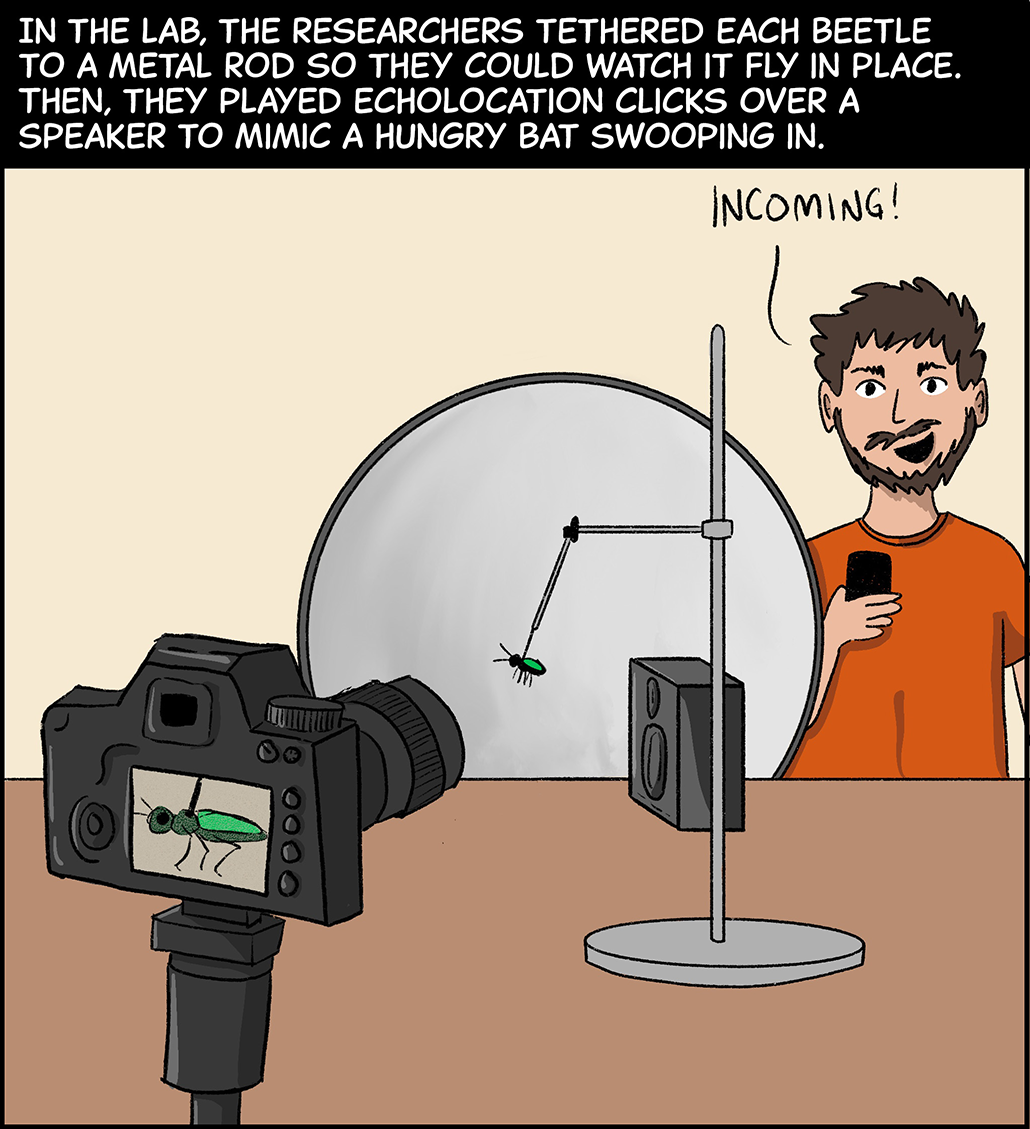

echolocation: (in animals) A behavior in which animals emit calls and then listen to the echoes that bounce back off of solid things in the environment. This behavior can be used to navigate and to find food or mates. It is the biological analog of the sonar used by submarines.

insect: A type of arthropod that as an adult will have six segmented legs and three body parts: a head, thorax and abdomen. There are hundreds of thousands of insects, which include bees, beetles, flies and moths.

maneuver: To put something in a desired or necessary position by using one or more skilled movements or procedures.

metal: Something that conducts electricity well, tends to be shiny (reflective) and is malleable (meaning it can be reshaped with heat and not too much force or pressure).

moon: The natural satellite of any planet.

nocturnal: An adjective for something that is done, occurring or active at night.

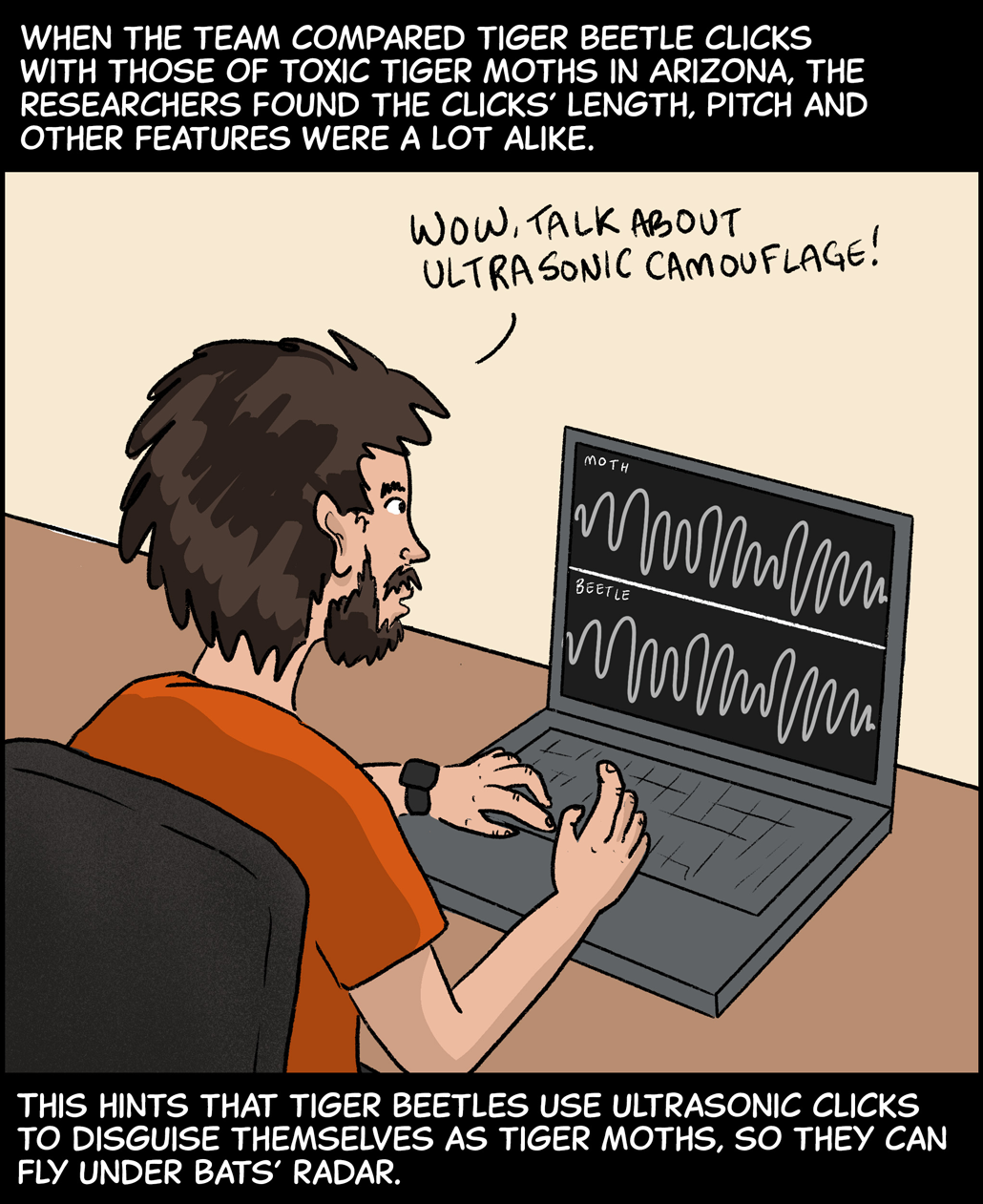

pitch: (in acoustics) The word musicians use for sound frequency. It describes how high or low a sound is, which will be determined by the vibrations that created that sound.

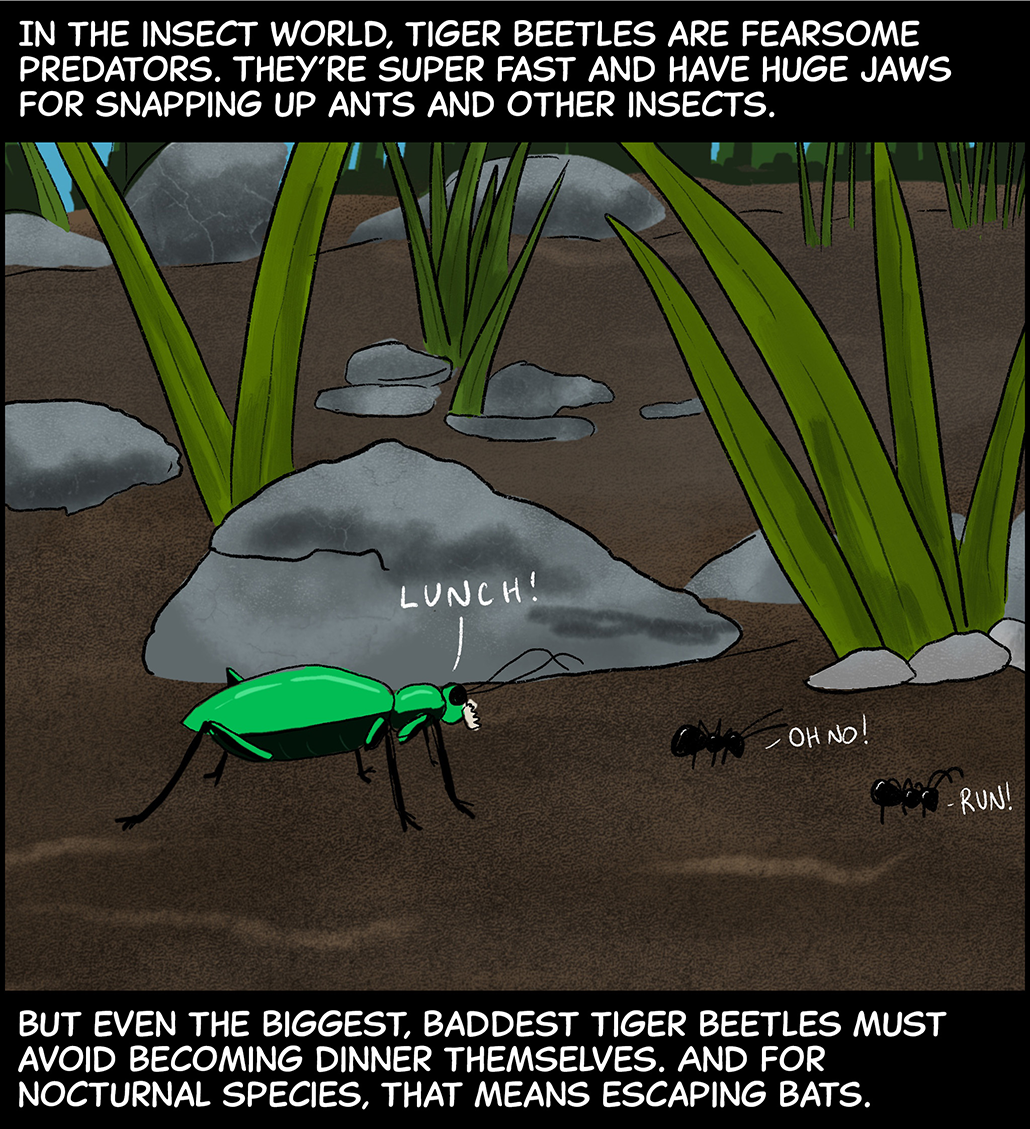

predator: (adjective: predatory) A creature that preys on other animals for most or all of its food.

prey: (n.) Animal species eaten by others. (v.) To attack and eat another species.

sound wave: A wave that transmits sound. Sound waves have alternating swaths of high and low pressure.

species: A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.

swarm: A large number of animals that have amassed and now move together. People sometimes use the term to refer to huge numbers of honeybees leaving a hive.

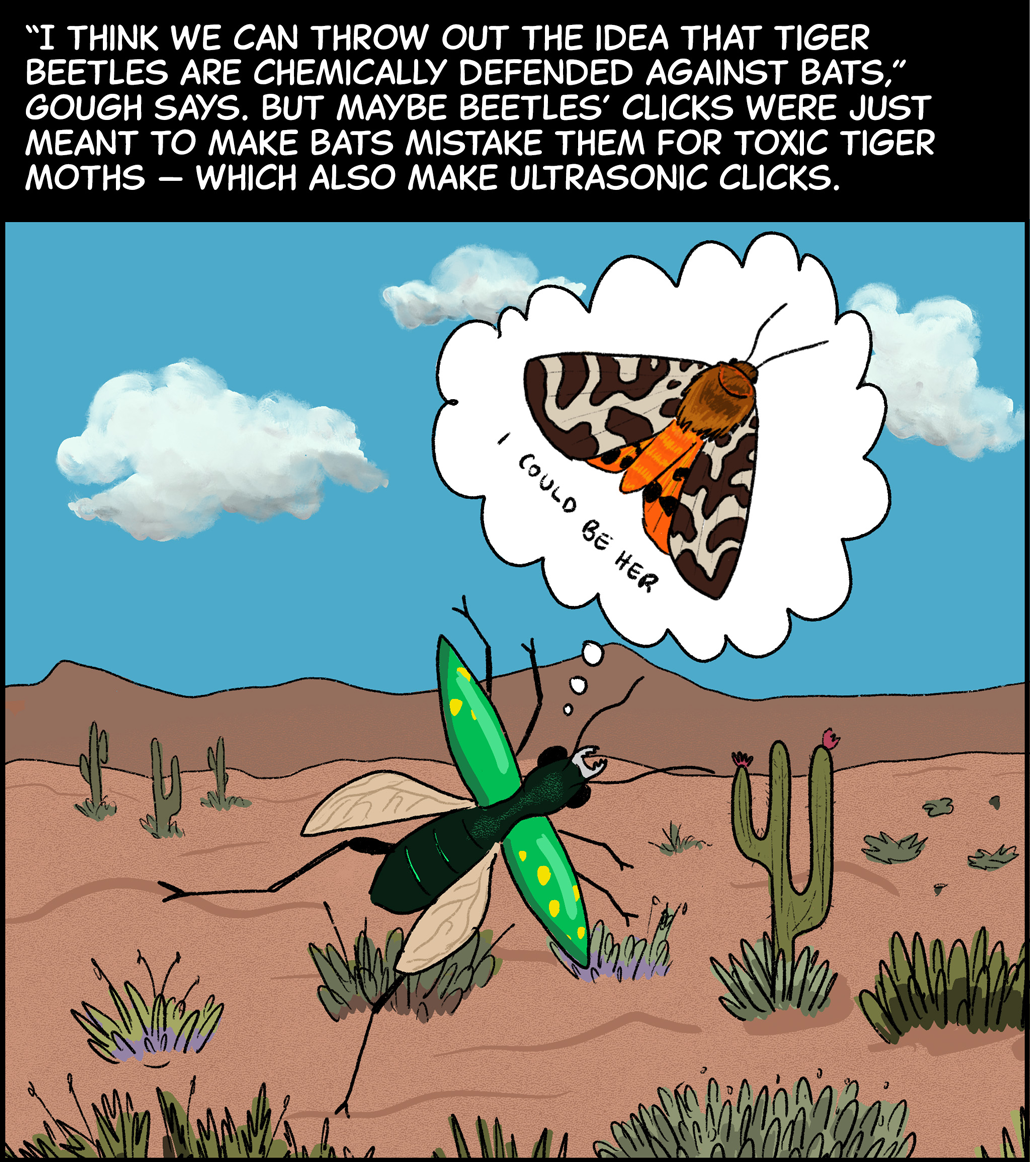

toxic: Poisonous or able to harm or kill cells, tissues or whole organisms. The measure of risk posed by such a poison is its toxicity.

translucent: The property of letting light through, but not being transparent. Usually, things viewed through a translucent material (such as frosted window glass) appear as hazy shapes with no detail.

wave: A disturbance or variation that travels through space and matter in a regular, oscillating fashion.

![Text (above top image): When beetles fly, they lift their outer forewings away from their beating hindwings. Image (top): A beetle lifts a pair of green and yellow-spotted wings, labeled “forewings,” up and away from its body. This allows a pair of translucent, labeled “hindwings,” to spread out from underneath. Text (above bottom image): But nocturnal tiger beetles pulled an unusual maneuver. “Right as they hear the bat sound, they go, ‘Uh oh!’ and they swing their [forewings] rearward,” says Gough. The beetles’ beating hindwings smacked their forewings, producing ultrasonic clicks. Image (bottom): The same beetle from before pulls its green and yellow-spotted hindwings back so that they overlap with the translucent hindwings. This creates a “bzzzz” sound.](https://www.snexplores.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/1030_bat_beetle_comic_6.png)

![Text (above image): Gough suspects such acoustic trickery may be common in the night sky. Many insects have ears tuned to bat calls, but little is known about how they use their ultrasonic sense. Image: A kid wearing a red sweatshirt looks up at a glowing porch light at night, which is swarming with insects. Text (below image): “If you look at your porch light at night, you see all kinds of insects that…we know can get eaten by bats,” Gough says. “What are some [anti-bat] strategies that other insects use?”](https://www.snexplores.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/1030_bat_beetle_comic_10.png)