Tracking Solar Storms

Electrical storms on the sun can send charged particles all the way to Earth.

By Emily Sohn

Sitting in the sun on a warm day can be relaxing, but the sun is not a peaceful place.

Every two days or so, our star spits out a billion-ton cloud of particles that go racing into space. These solar storms are called coronal mass ejections. The particles in the storms have electric charges.

|

|

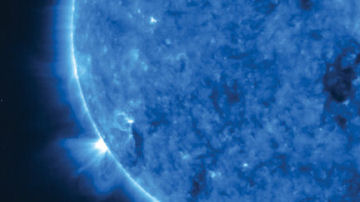

A solar storm, which appears as a white spot on the left side of this picture, lifts off the sun and heads into space—and possibly toward Earth. The sun isn’t really blue, but the camera scientists used to take this picture makes it look that color. |

| Howard et al./SECCHI Team, NRL, NASA |

Once in a while, the particles hit Earth. When they do, they can knock out power systems on land and interrupt satellites in space.

Now, for the first time, scientists have been able to follow coronal mass ejections from inside the sun’s atmosphere all the way to Earth’s orbit. This makes it possible for them to better predict when the particles might hit Earth.

A pair of spacecraft collects the measurements. One craft travels in front of Earth in its orbit around the sun. The other craft follows Earth. Together, the spacecraft make up the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO).

In the past, attempts to monitor coronal mass ejections focused on the sun from places along the line between the sun and Earth. But that view is too narrow. It doesn’t let scientists track the storms as accurately as they’d like. STEREO provides a better perspective.

Each STEREO craft has five telescopes that can view a coronal mass ejection at various points along its path. Scientists follow the particles by piecing together images from all the telescopes.

|

|

In this scientific illustration, a STEREO spacecraft studies a coronal mass ejection as the ejection moves away from the sun. |

| NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Scientific Visualization Studio |

The new images were taken in late January. They show a coronal mass ejection that is shaped like a crescent moon as is lifts off the sun. The storm then fans out and becomes wavier as it travels.

Scientists suspect that the coronal mass ejection changed shape—from a smooth crescent to a wavy one—because it interacted with the solar wind. This breeze of charged particles blows constantly from the sun. A better understanding of this interaction will help scientists make more accurate predictions about how quickly solar storms will travel to Earth.

By April, the two STEREO craft will be far enough apart to take three-dimensional pictures of the sun and its storms.—E. Sohn

Going Deeper:

Cowen, Ron. 2007. Stormy weather in space: Craft take panoramic view of solar eruptions. Science News 171(March 3):133. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20070303/fob5.asp .