Gender-affirming care improves the mental health of transgender youth

Laws limiting access to this treatment may harm already vulnerable kids, experts say

Proposed restrictions on gender-affirming health care are part of a recent wave of legislation that some LGBTQ advocates say discriminates against transgender people. Here, transgender-rights activists in Brooklyn, N.Y. protest legislation that would restrict trans rights.

Michael M. Santiago/Staff/Getty Images

Daniel’s birth certificate is marked “female.” But Daniel does not identify as exclusively male nor female. Daniel is nonbinary. “I’m masculine leaning,” the 18-year-old says.

Daniel knew they were not a girl by about age 4. But the disconnect between Daniel’s body and gender identity became unbearable during puberty. “I hated showers because I didn’t like looking at my body,” Daniel says. “I just felt really uncomfortable with the idea of being female.” At age 13, Daniel came out to their mother as transgender. Someone who is transgender has a gender identity that does not match the sex assigned to them at birth.

After coming out, Daniel started seeing a therapist who specialized in gender. The next year, they were referred to a doctor who prescribed testosterone. This hormone caused Daniel to develop more masculine features. For Daniel, the most important effect was a deeper voice. “My biggest problem with getting [seen as a girl] was that my voice was really high,” Daniel says. (Daniel’s last name is not being used to protect their privacy.)

Before starting hormone therapy, Daniel considered suicide. With testosterone, they’re happier with life. “I definitely feel more like myself. Like I was just existing before, but now I’m living — now that I’m open to everyone about who I am, and … I’m open to myself,” says Daniel. “Starting testosterone, for me, saved my life.”

Hormone therapy is just one method of gender-affirming health care. The term includes treatments that help people express their gender identity. This care looks different for people of different ages. In young kids, it involves letting them use a name and pronouns that match their gender. Adolescents may take drugs to delay puberty, followed by hormones. Some later undergo surgery.

Gender-affirming treatment is the standard of care for transgender people in the United States. About 1.8 percent of American high schoolers are transgender. That’s according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But some U.S. lawmakers have recently tried to make these treatments illegal.

In April, Arkansas became the first state to ban gender-affirming care for minors. Similar bills have cropped up in more than a dozen other states. Several of the proposals have failed. Still, experts warn, this legislation may harm the mental health of trans youth.

Limiting laws

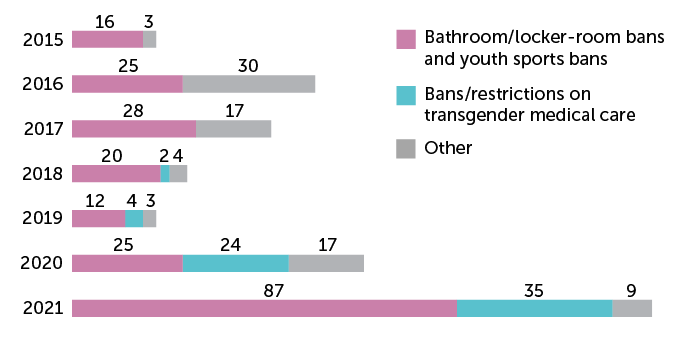

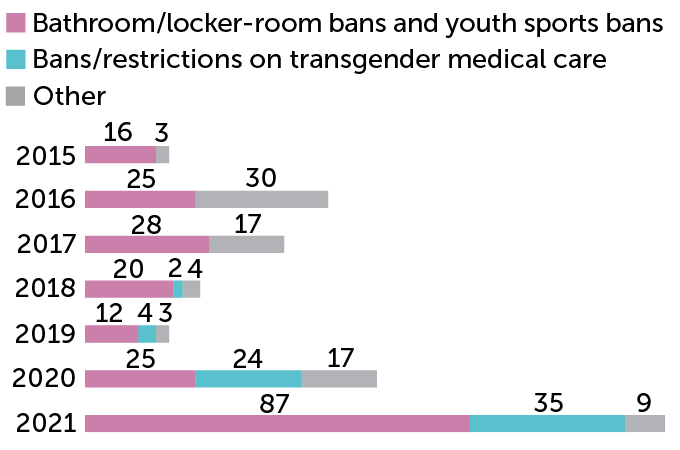

Recent U.S. state legislation seeks to bar transgender people from using bathrooms or competing on sports teams that match their gender identities. Other bills curb access to gender-affirming health care for minors.

Number of anti-transgender bills introduced in state legislatures, 2015–2021

“Even if the bills don’t pass … the damage is being done,” says Jason Klein. He’s an endocrinologist in New York City. That’s a doctor who specializes in hormones. Klein works at New York University Langone Health. “Many people across this country are already going to be hurt just by the ideas being put out by these bills.”

Those who support health-care restrictions say they want to protect children from procedures they may later regret. They also want to protect kids from any risks such medical treatments may pose. Those risks might include impacts on bone health and fertility. Yet the American Academy of Pediatrics endorses gender-affirming care. So do other medical associations. These groups say that restricting access to gender-affirming care could harm the mental health of trans youth. This population is already at severe risk of depression and self-harm. Transgender youth are three to four times as likely as their peers to have depression or anxiety. And they’re at much higher risk of suicide.

Gender-affirming care offers hope, says Jack Turban. He’s a child and adolescent psychiatry researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “All existing research suggests that gender-affirming medical interventions improve the mental health of transgender youth.”

Transitioning in childhood

For children who haven’t yet started puberty, gender-affirming care involves no medical treatments. Parents and doctors just support a child through a social transition. This may mean calling the child by a new name. A child might also start using the pronouns that fit their gender identity. In addition, parents can let a kid dress or wear their hair however they like.

Mental health care providers can help families through this process. “Sometimes, the kids need more conversation and time to think about their gender identity,” Klein says. “Sometimes, the parents need that. The kids are very solid and steady and know exactly who they are, and the parents might need some time to kind of adjust.”

Being supported through a social transition seems to boost mental health. Transgender children who have not socially transitioned have historically shown high levels of depression. But one recent study points to the benefits of social transitions. Among the more than 100 socially transitioned children studied, their ratings of depression and self-worth were about the same as for their non-transgender, or cisgender, siblings and peers. Researchers shared their findings four years ago in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

Some opponents of gender-affirming health care argue that young kids should not socially transition. The reason? A few studies have suggested that most people who identify as transgender in childhood will grow out of it. Other researchers think those findings are unreliable. They argue that the studies had used outdated criteria to label children as transgender. So, many kids in those studies may not have grown out of being transgender. They just weren’t transgender in the first place.

Scientists are still learning how gender evolves with age. “We have to be honest. We don’t know so much about it,” says Annelou de Vries. She’s a child and adolescent psychiatrist in the Netherlands. She works at the Amsterdam University Medical Centers. For kids who are unsure about their gender, there are non-permanent treatments. These can allow young children to safely explore their gender as they reach adolescence.

Pausing puberty

At the start of puberty, children who are questioning their gender may take puberty blockers. These drugs suppress the body’s natural release of sex hormones. Those hormones — estrogen and testosterone — cause the body to develop permanent, gender-specific features. For instance, women grow breasts and men grow facial hair. Doctors may inject puberty blockers or insert a small drug-delivery implant in the upper arm.

Delaying puberty allows kids to go through their early teen years without going through body changes that don’t match their gender identity. “These medications are fully reversible,” says Russell Toomey. He’s a family studies and human development researcher. He works at the University of Arizona in Tucson. If someone stops taking puberty blockers, their body will pick up where it left off and proceed through puberty.

Doctors have used puberty blockers for decades to treat children who start going through puberty too early. So these medications are hardly new. But recent bills would forbid doctors from prescribing them to transgender youth, despite their benefit. In one study, researchers analyzed a survey of more than 20,000 U.S. transgender adults. Nearly 17 percent had wanted puberty blockers while growing up. Only 2.5 percent got them. Adults who had access to the drugs were 70 percent less likely to have considered suicide. Researchers shared that finding in the April 2020 Pediatrics.

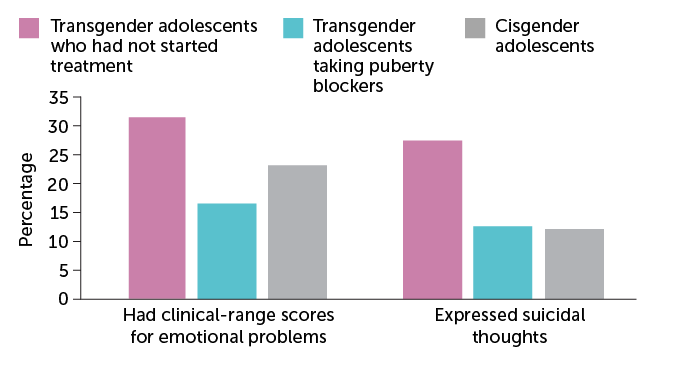

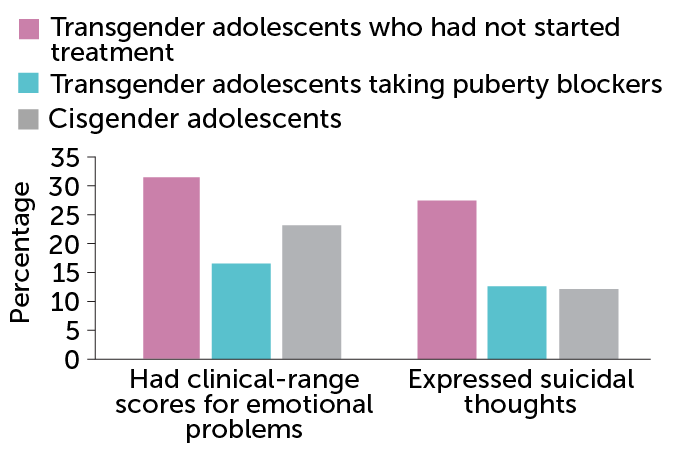

Another study on puberty blockers included 1,100 kids and teens in the Netherlands. Kids who had visited a gender clinic but not yet started puberty blockers had more emotional problems than their non-transgender peers. They also showed more suicidal tendencies. But transgender kids taking puberty blockers had similar or better mental health than non-trans peers. Researchers reported that in the June 1, 2020 Journal of Adolescent Health.

Closer to OK

Emotional problems, such as depression or anxiety, that would qualify for mental-health care were much more common among transgender teens who had not started puberty blockers than in those who received those medications. These results come from a study of 1,100 Dutch kids and teens. Similarly, a higher percentage of transgender teens who had not received puberty blockers expressed suicidal thoughts than trans peers who had received the medications and non-transgender teens.

Differences in mental health among Dutch adolescents

Daniel wishes they’d had the opportunity to take the medications. “If I’d been on [puberty] blockers, things would have been a lot easier for me,” Daniel says. “I would have still struggled, but it would have been easier to handle.”

One possible downside: Puberty blockers delay bone development. These drugs interrupt the rapid buildup of bone density that generally happens in the early teen years. In theory, that could leave them with weaker bones in adulthood. But existing data suggest that bone growth catches up once people stop taking puberty blockers.

To be safe, doctors give special instructions to patients on these drugs. “We have them take vitamin D and calcium,” says Johanna Olson-Kennedy. She works at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. There, she practices pediatric and adolescent medicine. “We stress the importance of weight-bearing exercise,” she adds. Exercise is crucial for building dense bone.

Hormone therapy

Older transgender teens may start taking gender-affirming hormones, as Daniel did. Medical guidelines recommend this treatment start around age 14 to 16. Masculinizing hormone therapy involves taking testosterone. The hormone deepens someone’s voice and promotes facial hair to grow. It also suppresses menstruation and breast development. Daniel takes testosterone through injections. Other people may use a skin ointment or patch.

Feminizing hormone therapy involves taking estrogen through a pill, patch or injection. This causes breast development. It also slows body hair growth and decreases muscle mass. Typically, estrogen must be paired with a drug to block the body’s natural testosterone.

Some effects of hormone therapy are permanent. Voice deepening and breast development are. Changes in muscle mass and fat distribution, however, are reversible if treatment stops.

Body changes

Transgender teens about 14 to 16 years old may start taking the masculinizing hormone testosterone or the feminizing hormone estrogen. These hormones promote body changes that align with a person’s gender identity.

Effects of hormone therapies

Testosterone

- Suppressed menstruation

- Body fat redistribution

- Voice deepening

- Increased muscle mass

- Facial and body hair growth

Estrogen

- Decreased muscle mass

- Body fat redistribution

- Skin softening

- Breast growth

- Decreased body hair growth

Research shows that hormone therapy reduces risk of self-harm and improves body image among transgender teens. In one study of 47 young transgender teens, 21 expressed suicidal tendencies before hormone therapy. That number dropped to six after treatment. The study appeared in the September 2019 Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology. Another study surveyed 86 teens on hormone therapy. On average, these kids were happier with their bodies after treatment. Participants rated their body dissatisfaction on a scale from 0 (none) to 116 (most dissatisfied). Ratings fell from an average of 71 before treatment to 51 after roughly a year of treatment. Researchers shared these data in the April 2020 Pediatrics.

Hormone therapy is generally considered safe. But it’s not risk-free. Testosterone and estrogen can both impact fertility. Their effects vary from person to person. People who want to have children later can freeze their eggs or bank their sperm before starting hormones. But teens who have taken puberty blockers may be less likely than others to produce viable eggs or sperm.

Hormones also may put people at higher risk for common gender-specific conditions. For example, transgender women who take estrogen may have a higher risk of breast cancer than men. But trans women are not at higher risk of breast cancer than other women, says Joshua Safer. He directs the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery in New York City. Likewise, transgender men taking testosterone may, like other men, be at risk of high cholesterol.

Right timing

For young kids, gender-affirming health care involves supporting a child through a social transition. This may involve a change in name, pronouns and clothing style. Older adolescents may receive medical treatments, including puberty blockers, hormone therapy or surgery.

When health care support is considered

| Age (years) | Options |

| <8 | Social transition |

| 8–14 | Puberty blockers |

| >14 | Hormone therapy |

| 18 (with exceptions) | Surgery |

Beyond hormone therapy, some transgender people undergo gender-affirming surgery. Medical guidelines do not recommend genital surgery for minors. However, some young transgender men and nonbinary people may have masculinizing chest surgery before age 18. This procedure is suitable for people who have severe distress or discomfort from unwanted breast development. Surgery “is a major decision,” says Turban. It “requires careful coordination between a family and their physicians.” Like other types of gender-affirming care, surgery has been shown to improve mental health and quality of life.

Risk of regret

Every stage of gender-affirming care involves careful thought. Kids and their parents should have many conversations with their doctors and mental-health-care providers. And adolescents and their parents must give informed consent before any medical procedures. “It’s not that you decide on your 12th birthday where you are when you’re 21,” de Vries says.

Some lawmakers have argued that minors who take puberty blockers or hormones may later regret it. Regret is a risk. But current research suggests that regret following gender-affirming care is rare, Turban says.

One team tracked 55 transgender people from adolescence to adulthood. All took puberty blockers and hormones as teens. As adults, they also had gender-affirming surgery. Afterward, this cohort had a similar quality of life and happiness as their non-trans peers. None regretted treatment. Researchers shared those findings in 2014 in Pediatrics.

Similar results emerged from a recent review of more than two dozen studies. In total, they included nearly 8,000 transgender patients who had gender-affirming surgeries. Only about 1 percent regretted treatment. The review was published in the March issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery-Global Open.

Some trans people do return to living as the gender assigned to them at birth. This process is known as detransitioning.

Research shows that external factors, such as social stigma, can be a reason for this. In one survey of nearly 28,000 transgender adults, about 2,200 had detransitioned. More than one in every three said pressure from parents was a reason. Close to one in three reported pressure from their community. Roughly 11 percent said that changes in their gender identity factored into their detransition. Those data appear in the June LGBT Health.

Legal impacts

Laws in places that forbid gender-affirming care could have broad impacts. They may portray this care as experimental or dangerous, making trans kids afraid to ask for help, Klein says. Parents may also be reluctant to seek help for their kids even in places where this treatment is legal.

Health care bills are just one part of a wave of legislation that discriminates against transgender people, some LGBTQ advocates say. A new law in Tennessee, for instance, requires some public places to post signs if they let trans people use bathrooms that match their gender identity. And several states now forbid transgender kids from playing on sports teams that match their gender identity. Those states include Florida, Mississippi and Tennessee.

“We know that a major driver of mental health problems among transgender youth is rejection of their gender identity,” Turban says. “Imagine that you heard powerful politicians pronouncing on the national stage that you’re confused, invalid and dangerous to people in bathrooms and sports leagues. It’s extraordinarily difficult for a child not to be negatively impacted by this.”

Research is just emerging on how new legislation may impact transgender kids and their families. One small study surveyed parents of transgender children. Parents expressed anxiety about the increased stigma their kids may face. They also were worried about the health impacts of not having access to gender-affirming care. “I am afraid for those kids who might find death preferable to being forced to go through … puberty for the wrong gender,” said one mother. Researchers described what they learned in the July 29 Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity.

Daniel can relate. “It’s frustrating. It angers me,” they say. “What is the point of stopping people from being who they are, and doing things that could possibly save their life?”

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young adults ages 15 to 29 as of 2016. If you or someone you know is suffering from suicidal thoughts, please seek help. In the United States, you can call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988. Please do not suffer in silence.