anatomy: The study of the organs and tissues of animals. Or the characterization of the body or parts of the body on the basis of structure and tissues. Scientists who work in this field are known as anatomists.

antibodies: Any of a large number of proteins that the body produces from B cells and releases into the blood supply as part of its immune response. The production of antibodies is triggered when the body encounters an antigen, some foreign material. Antibodies then lock onto antigens as a first step in disabling the germs or other foreign substances that were the source of those antigens.

artificial intelligence: A type of knowledge-based decision-making exhibited by machines or computers. The term also refers to the field of study in which scientists try to create machines or computer software capable of intelligent behavior.

biology: The study of living things. The scientists who study them are known as biologists.

blood vessel: A tubular structure that carries blood through the tissues and organs.

cell: (in biology) The smallest structural and functional unit of an organism. Typically too small to see with the unaided eye, it consists of a watery fluid surrounded by a membrane or wall. Depending on their size, animals are made of anywhere from thousands to trillions of cells.

cell membrane: A structure that separates the inside of a cell from what is outside of it. Some particles are permitted to pass through the membrane.

chemical: A substance formed from two or more atoms that unite (bond) in a fixed proportion and structure. For example, water is a chemical made when two hydrogen atoms bond to one oxygen atom. Its chemical formula is H2O. Chemical also can be an adjective to describe properties of materials that are the result of various reactions between different compounds.

cholesterol: A fatty material in animals that forms a part of cell walls. In vertebrate animals, it travels through the blood in little vessels known as lipoproteins. Excessive levels in the blood can signal risks to blood vessels and heart.

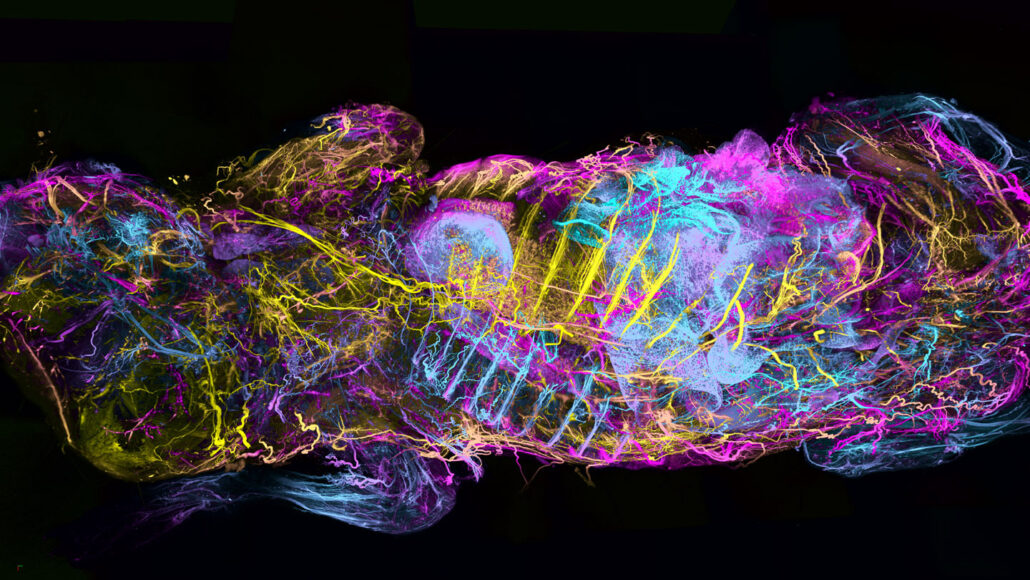

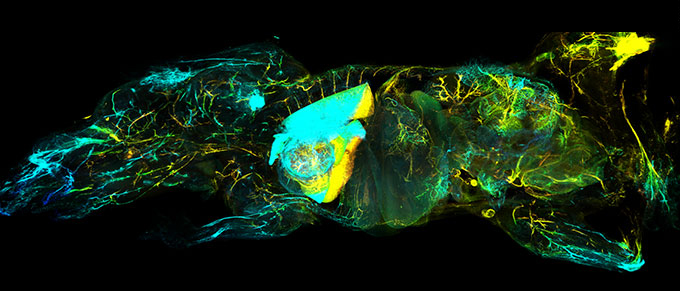

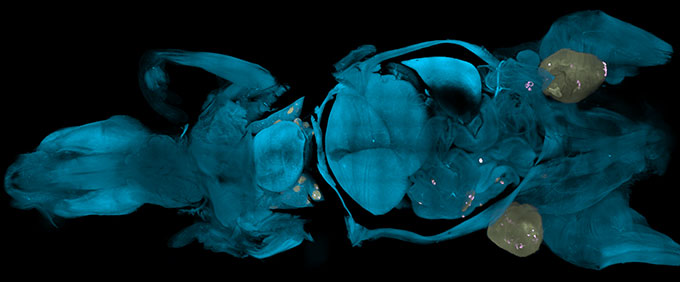

fluorescent: (v. fluoresce) Adjective for something that is capable of absorbing and reemitting light. That reemitted light is known as fluorescence.

fruit flies: Tiny flies belonging to the species Drosophila melanogaster. Scientists often use these short-lived animals as a “guinea pig” for lab studies because they are easy to grow, can mature into adults in a short time and their bodies share many of the same traits and responses as more complex animals — including mammals.

hue: A color or shade of some color.

immune: (adj.) Having to do with immunity. (v.) Able to ward off a particular infection. Alternatively, this term can be used to mean an organism shows no impacts from exposure to a particular poison or process. More generally, the term may signal that something cannot be hurt by a particular drug, disease or chemical.

intelligence: The ability to collect and apply knowledge and skills.

membrane: A barrier which blocks the passage (or flow through) of some materials depending on their size or other features. Membranes are an integral part of filtration systems. Many serve that same function as the outer covering of cells or organs of a body.

molecule: An electrically neutral group of atoms that represents the smallest possible amount of a chemical compound. Molecules can be made of single types of atoms or of different types. For example, the oxygen in the air is made of two oxygen atoms (O2), but water is made of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom (H2O).

nerve: A long, delicate fiber that transmits signals across the body of an animal. An animal’s backbone contains many nerves, some of which control the movement of its legs or fins, and some of which convey sensations such as hot, cold or pain.

nervous system: The network of nerve cells and fibers that transmits signals between parts of the body.

network: A group of interconnected people or things. (v.) The act of connecting with other people who work in a given area or do similar thing (such as artists, business leaders or medical-support groups), often by going to gatherings where such people would be expected, and then chatting them up. (n. networking)

neuroscientist: Someone who studies the structure or function of the brain and other parts of the nervous system.

organ: (in biology) Various parts of an organism that perform one or more particular functions. For instance, an ovary is an organ that makes eggs, the brain is an organ that makes sense of nerve signals and a plant’s roots are organs that take in nutrients and moisture.

pathogen: An organism that causes disease.

protein: A compound made from one or more long chains of amino acids. Proteins are an essential part of all living organisms. They form the basis of living cells, muscle and tissues; they also do the work inside of cells. Antibodies, hemoglobin and enzymes are all examples of proteins. Medicines frequently work by latching onto proteins.

psychedelic: An adjective (especially popular in the 1960s) that refers to the abnormal mental experiences (such as hallucinations) brought on by use of certain drugs (such as LSD), and sometimes described as swirling, kaleidoscope-like, color patterns.

sewer: A system of water pipes, usually running underground, to move sewage (primarily urine and feces) and stormwater for collection — and often treatment — elsewhere.

simulate: To deceive in some way by imitating the form or function of something. A simulated dietary fat, for instance, may deceive the mouth that it has tasted a real fat because it has the same feel on the tongue — without having any calories. A simulated sense of touch may fool the brain into thinking a finger has touched something even though a hand may no longer exists and has been replaced by a synthetic limb. (in computing) To try and imitate the conditions, functions or appearance of something. Computer programs that do this are referred to as simulations.

species: A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.

system: A network of parts that together work to achieve some function. For instance, the blood, vessels and heart are primary components of the human body's circulatory system. Similarly, trains, platforms, tracks, roadway signals and overpasses are among the potential components of a nation's railway system. System can even be applied to the processes or ideas that are part of some method or ordered set of procedures for getting a task done.

tactic: An action or plan of action to accomplish a particular feat.

tissue: Made of cells, it is any of the distinct types of materials that make up animals, plants or fungi. Cells within a tissue work as a unit to perform a particular function in living organisms. Different organs of the human body, for instance, often are made from many different types of tissues.

tumor: A mass of cells characterized by atypical and often uncontrolled growth. Benign tumors will not spread; they just grow and cause problems if they press against or tighten around healthy tissue. Malignant tumors will ultimately shed cells that can seed the body with new tumors. Malignant tumors are also known as cancers.