Stunning trilobite fossils include never-before-seen soft tissues

They point to the weird way trilobites ate — and perhaps why they went extinct

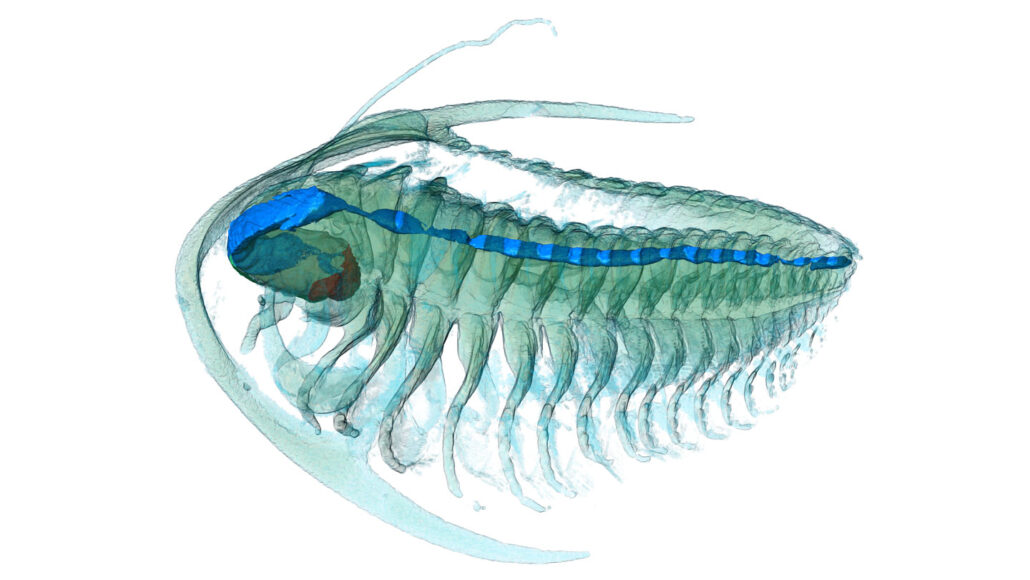

In this 3-D map of a trilobite fossil, the digestive tract (blue) appears almost completely intact.

© Arnaud Mazurier/University of Poitiers

In rocks from Morocco, scientists have unearthed the best preserved trilobites ever found. The lifelike fossils offer new clues to the biology of these extinct sea creatures.

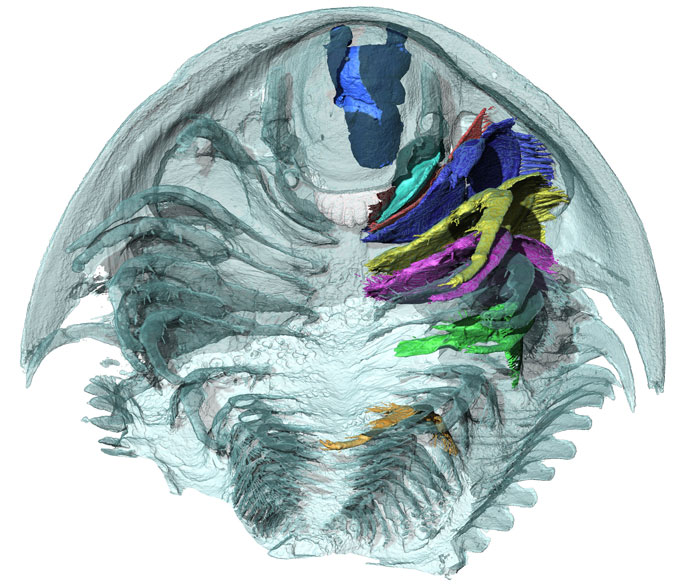

The fossils are so well preserved that they show their antennae, legs and digestive system. Even soft tissues are clearly visible in 3-D. Such parts typically break down as the animals turn into fossils.

Researchers shared these new details in the June 28 Science.

“These trilobite fossils represent the most complete specimens found,” says John Paterson. He led the team behind the discovery. A paleontologist, Paterson works at the University of New England. It’s in Armidale, Australia.

Preservation by volcano

Trilobites lived in the ocean for about 270 million years. They died out some 252 million years ago. These arthropods then became one of the most iconic fossil animals.

And their fossils are extremely common. Why? Their hard exoskeletons fossilize fairly easily. But it’s rare to find any trace of the creatures’ soft parts.

Paterson’s team wondered why their fossils had preserved the soft tissues so well. To find out, they enlisted a geologist at Pomona College in Claremont, Calif. Robert Gaines is an expert in how the soft parts of animals become fossils.

Here, it started when a volcano exploded, erupting superheated ash. This ash mixed with seawater at coastal sites, covering the trilobites. This would have entombed the critters in hours to days.

The key step here: Ash hit the water before it hardened around the animals. Without the cooling effects of ocean water, that scalding ash would have burned up the critters.

Gaines has studied similarly well-preserved older fossils. One is Aegirocassis, an alien-like arthropod. “I recognized the similarities immediately,” Gaines says. “They pointed to the same process [at work] more than 20 million years earlier.”

Trilobite insights

The Moroccan fossils open new windows onto trilobites’ lives and history. And they confirm some ideas that scientists had proposed based on less-complete trilobite fossils.

This shows “the power and importance of exceptional preservation,” says paleontologist Nigel Hughes. He’s based at the University of California, Riverside and did not take part in the new work. Here, Hughes says, “the clarity of the preservation is astonishing.”

For instance, trilobites’ many pairs of legs run from their head to their torso. The new fossils confirm these animals used those limbs to eat. They chewed food along a central groove while passing bits of food toward a tiny mouth.

“Food processing took place along the entire length of the animal,” Hughes says.

This differs from other arthropods, such as crustaceans. Those animals have more specialized limbs which they use for things such as self-defense or swimming. Trilobites, it seems, used their limbs for less specialized uses.

“It seems likely that this basic limb style endured throughout the history of trilobites,” Hughes says. And, he adds, it may be part of why they ultimately died out. Finding more well preserved trilobites could help answer questions on how they evolved over time.

Volcanic eruptions are not that uncommon over Earth’s long history, Paterson notes. And that suggests well-preserved fossils may be more common than scientists had thought.