Trio wins 2020 Nobel for discovery of hepatitis C

It took 50 years from discovery to a cure for this liver-damaging virus

Identifying this virus — hepatitis C — dramatically cut the number of people who would become infected through blood transfusions.

CDC

About 71 million people worldwide have chronic liver disease due to a hepatitis C infection. Some 400,000 people die each year from cancer and other complications of this infection. Three scientists have just won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for their discovery of the virus responsible.

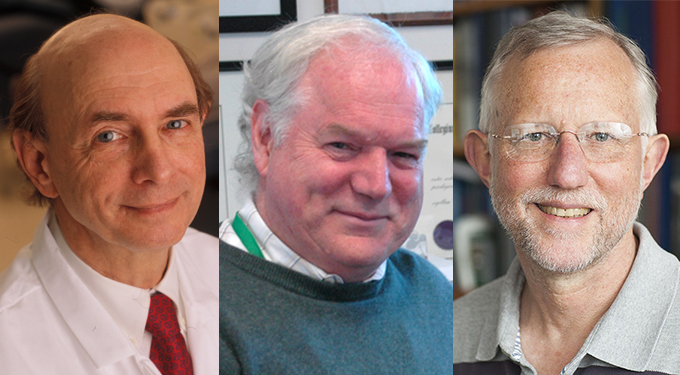

Harvey Alter works for the U.S. National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, Md. Michael Houghton now works at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. And Charles Rice now works of The Rockefeller University in New York City. All three are virologists, people who study viruses.

The Nobel Assembly of the Karolinska Institute announced the winners on October 5. Each scientist will take home a third of the 10 million Swedish kronor award (a bit more than $1.1 million).

“This [win] is a bit overdue,” says Dennis Brown. He is the chief science officer of the American Physiological Society. It often takes decades for a finding to be recognized by the Nobel committee. One reason for this year’s choice may be that people are thinking more about viruses because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It puts “virology and viruses in the public eye,” Brown says. It might also show that “when we have well-funded people working on these viruses, we can actually do something about them.”

What the winners did

The way most people now pick up hepatitis C is when users of intravenous drugs share virus-contaminated needles. But that was not true when the researchers made their discoveries in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s. Back then, blood banks didn’t know to screen for the virus from donated blood. So blood transfusions were an important source of infections.

Alter worked at a large NIH blood bank when hepatitis B was discovered in the 1960s. (For that discovery Baruch S. Blumberg took home half the 1976 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.) Blood screening could scout for that virus and keep infected blood from being shared. Still, some patients got hepatitis. Alter and his colleagues showed in the mid- and late-1970s that a different germ caused their infection. They dubbed it the “non-A, non-B” hepatitis virus.

A bit more than a decade later, Houghton found a way to pull bits of the virus’s genetic material from the blood of infected chimpanzees. It took so long because Houghton “had to wait until the technology was available,” Brown says. Houghton eventually created a test to screen for the virus in blood.

Over seven years, “we must have tried 30 or 40 methods” to extract, or clone, the virus Houghton said during a news conference. “It took another two years for us to get that to work,” he recalled.

Over six to nine months, the researchers showed again and again that this virus was the source of one small piece of genetic material they had cloned (copied) from the blood. It took even more work to convince other scientists that they’d snagged the virus.

The test Houghton’s team created was used to screen blood all around the world. That screening would greatly cut the rate of hepatitis C infections, said Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam. She works at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden. She was part of the selection committee and spoke during the announcement of the prize. Until that blood test, getting a blood transfusion “was a bit like Russian roulette” said Nils-Göran Larsson. He was part of this year’s Nobel selection committee.

Still, one important mystery remained. Could this virus act alone in causing liver disease in people? Rice and his colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., stitched together genetic fragments of the virus. This work “provided conclusive evidence,” said Karlsson Hedestam, that the virus was all that was needed to cause disease.

Finding a cure proved challenging

This work also set the stage for drugs to cure infections caused by the virus, notes Richard Lifton. He’s president of The Rockefeller University.

For many years after Houghton identified the virus’s genetic makeup, it still wasn’t possible to grow the virus in the lab. Yet that would be a first step in creating a drug.

“I thought this would be a very short-lived area of [work] for us,” Rice said of studying how the virus copies itself. In fact, hepatitis C proved quite challenging. Rice led a team that eventually found a missing piece at the end of the virus that allows cells to copy it. The stitched-together virus containing that piece caused disease in chimpanzees.

Houghton is now working on a vaccine against this virus. “You need a vaccine to prevent [infection],” he says, “not just drugs to treat [it].”

Money in Alfred Nobel’s will created the prizes that now carry his name. But that will says no more than three people can share the prize in any one category. Some people who made important discoveries in a field may therefore get left out. For instance, some scientists had predicted Ralf Bartenschlager of Heidelberg University in Germany would share the prize with Rice. Bartenschlager had come up with a pivotal technique — how to grow the virus in cells — that enabled the development of a drug to fight it.

“It’s a long story, a 50-year saga,” Alter said of the route to finding this virus and being able to cure people of it. It’s important to keep an investigation going even “when you don’t know where you’re going.” At an October 5 news conference, he explained, when dealing with such “a persistent virus, persisting research paid off.”

Staff writer Jonathan Lambert also contributed to this story.