Tropical cyclones are getting more sluggish

How speedily the storms move across the landscape has been slowing, which could increase flooding

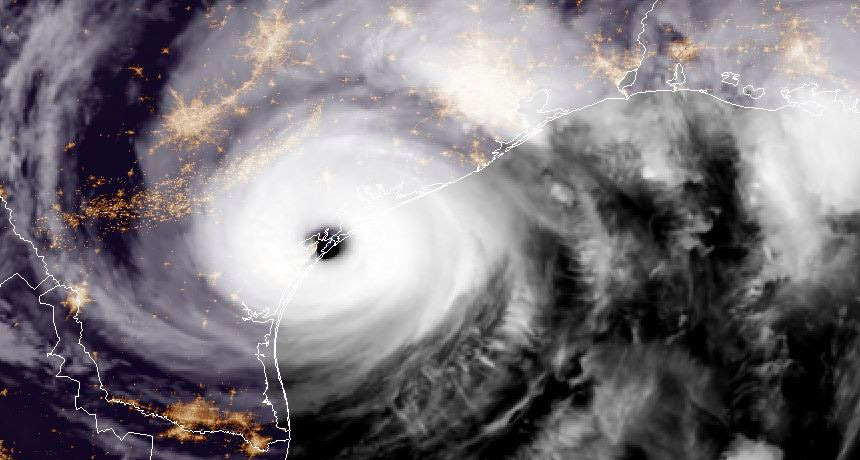

Tropical cyclones, such as 2017’s Hurricane Harvey (shown making landfall), have slowed down. That could make them more dangerous.

NOAA

Tropical cyclones aren’t as speedy as they used to be. They still spin rapidly. But they often travel at a more leisurely path down across the landscape, a new study finds.

Cyclones are fierce, swirling storms that form over oceans. Those in the Atlantic Ocean are called hurricanes. Today these storms move 10 percent slower, on average, than nearly 70 years ago. And that matters because as they trek across the landscape, these slowpokes can dump more rain — causing more flooding — and spend more time lashing these areas with their winds.

James Kossin works at the National Centers for Environmental Information in Madison, Wisc. It’s part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This scientist looked at how quickly tropical cyclones have been moving across the planet. He focused on changes between 1949 and 2016.

Story continues below image.

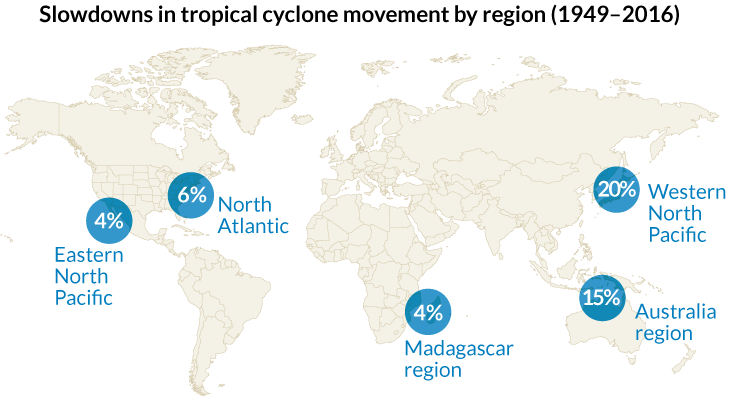

Storms have been traveling more slowly almost everywhere, he found. But the slowdown differed by region. He found the biggest slowing in the Northern Hemisphere.

Over the same nearly 7-decade period that he studied, climate change has been warming our world. Earth’s average surface temperature has climbed by about half a degree Celsius (0.9 degree Fahrenheit).

Scientists think tropical cyclones that form over warmer waters will, on average, spin faster. That translates to speedier winds. The new study suggests that climate change also is slowing the speed at which these storms cross the landscape.

Kossin shared his findings June 7 in Nature.

Trek slows most after landfall

The cyclone slowdown was especially obvious as storms moved over land. Those that started in the western North Pacific, such as near Japan, slowed by 30 percent. Those coming from the North Atlantic are moving 20 percent more slowly over land, says Kossin.

Tropical storms get pushed around by winds and air currents across the globe. Climate warming has been slowing this air movement in tropical areas. Kossin now finds that climate change also seems to be slowing down cyclones.

What also concerns scientists: Global warming could increase how much cloud water the atmosphere can hold. That means storms could collect more moisture before dumping it as rain.

Christina Patricola is an atmospheric scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. The new study makes an important link between the pace of tropical cyclones and the slowing winds around the planet (due to global warming), she says in a commentary about the new findings. Kossin correctly guessed, she notes, that if climate change is generally slowing down air movement, tropical cyclones also should slow.

It’s not clear whether storms will keep slowing, she notes. Right now, scientists can’t predict how cyclone slowing might vary across the planet.

One recent slowpoke was 2017’s Hurricane Harvey. It hovered over southern Texas for almost 5 full days. During this time it dumped an average of 76 centimeters (30 inches) of water across a region in which some six million people live. If you had stacked all of that water over New York City (a far smaller area), it would have reached a height of 68 meters (224 feet)! At the height of Harvey’s fury, this storm also spawned more than 30 tornadoes in Texas.

Some scientists now ask: Could such a mega-storm be a sign of things to come?