The truth about zits

How germs help keep your skin healthy — or make it break out

Scientists are working to understand the conditions that lead to clear skin versus breakouts of unsightly acne. And as breakouts are common, particularly among teens, research on new treatments is also underway.

Maria Morri/ Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Have you ever woken up in the morning only to feel a throbbing ache on the side of your nose? You wander into the bathroom, and — horror of horrors! — a huge red zit sprouted in the middle of the night. If you’re lucky, this doesn’t happen to you on school picture day or the night of a dance. But it could. At some point, pimples will erupt on the face of about 17 in every 20 people. This unpleasant skin condition, known as acne, plagues teens more than any other age group.

Acne hurts. And it can be embarrassing. But some lucky people never get zits — not even as teens. Rumors abound about what causes or prevents acne. Some people blame outbreaks on a diet too rich in dairy products or on sloppy personal hygiene. The truth, it turns out, is more complicated. While hygiene and diet may play some role in an outbreak, teens could cut out all milk and cheese and wash their faces twice a day and still break out.

So what triggers acne? Several factors make a difference. A person’s DNA — the genetic code that tells cells how to grow — can make some people more prone to acne. So can levels of hormones in the body and the particular bacteria that take up residence on the skin.

Scientists are particularly interested in one bacterium. It’s called Propionibacterium (PRO-pee-OH-nee-bak-TEER-ee-um) acnes, or P. acnes for short. It takes its name from where it thrives — inside pimples. This germ usually helps keep skin healthy. But it can have a disfiguring alter ego, sometimes making people break out. Researchers hope to someday develop treatments that use beneficial P. acnes bacteria to fight cousins that promote pimples. Other researchers are looking at new ways to heal acne using colored light.

A party in the pores

Vineet Mishra remembers getting a zit on his nose when he was a teen. “It was stressful,” he recalls. This dermatologist at UT Medicine, part of the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, has now seen plenty of cases far worse than his own. Some people experience outbreaks that blanket their entire face, neck, shoulders, chest or back.

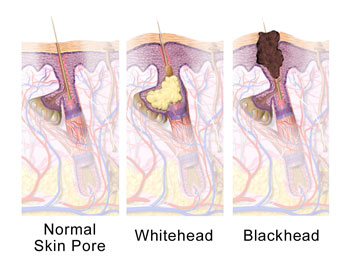

Simply put, a pimple is an inflamed spot on the skin. It develops after a small opening in the skin, called a pore, becomes clogged with oil, bacteria, sweat, dirt or dead skin. The body doesn’t like having all that gross stuff stuck inside. So the immune system, which is responsible for fighting infections, may kick into action. In order to clear out damaged cells and start repairs, the immune system sends extra blood and chemicals to the problem area. Often, the area reddens and swells up. This is called inflammation, and it usually means that the body is working hard to repair itself.

But sometimes the body overreacts. This is especially likely if you pick at the sore spots. Picking at a pimple “will produce more inflammation, making the area redder, more painful and even more swollen,” says Mishra.

A clogged pore that hasn’t closed up completely forms a tiny pimple called a blackhead. A whitehead happens when the pore seals up and swells with inflammation. Some unlucky people also get large lumps or even oozing sores.

These hormones also tend to make glands in the skin boost their production of sebum. That bonus oil means there’s a higher chance that pores will clog. What’s more, the P. acnes germs love to eat sebum. So the more of this greasy substance that builds up on the skin and in the pores, the faster these germs can grow. And that means there will be more germs around to colonize the pores, promoting zits.

Acne usually all but disappears in adulthood. By then, the body has cut back on levels of many hormones that had gone into overdrive during puberty. So the skin produces less sebum, which means fewer pores risk becoming clogged.

The bugs on your face

P. acnes can be found on everyone’s face — all the time. But don’t start madly trying to wipe or scratch these bacteria off! They are a normal part of a vast community of germs that live on skin. “We are not just humans. We are colonized by many, many bacteria,” explains Huiying Li, of the University of California in Los Angeles. As a microbiologist, she studies bacteria.

Some residents of a microbiome can make people very sick. Most instead coexist peaceably with their human hosts. In fact, many actually offer services to their hosts. Some help people digest food. Others produce chemicals that the body needs but cannot make.

P. Acnes usually helps break down sebum. As long as pores are open, this bacterium helps maintain a protective barrier over the skin’s surface. But when P. acnes gets trapped inside a clogged pore, these microbes can trigger painful inflammation.

Li, Weinstock, and colleagues suspected that people who are more prone to acne might host bigger populations of P. acnes. More microbes, they thought, might up the risk that some would settle down inside a clogged pore. To test this idea, the researchers recruited 49 acne patients and 52 people with healthy skin. They removed bacteria from the volunteers’ noses using sticky cleansing strips about the size of band-aids. To Li’s surprise, they found the same number of P. acnes in both groups.

Then, the researchers took a closer look at the different types, or strains, of P. acnes that they had retrieved. To do that, they used a technique known as ribotyping. Here, the researchers separated out a piece of DNA from the bacterial cell. Then they compared it to the DNA of other bacteria. With this method, the researchers turned up hundreds of different strains of P. acnes. They selected 10 of the most common strains, naming them RT1, RT2, RT3 and so on. “RT” stands for “ribotype.”

Each strain has its own strategy for battling other bacteria. Sometimes, these conflicts lead to acne. The researchers don’t yet know exactly what weapons the strains bring to these battles. Weinstock speculates that strains RT4 and RT5 might produce chemicals that make the skin a less attractive home for other types of P. acnes. If those chemicals also cause nasty pimples, then they will make people’s faces less attractive, too!

Weinstock thinks RT6, the strain more often found on healthy skin, must use a different strategy that helps keep zits away. He doesn’t know what that strategy is yet, but one possibility is that RT6 might make a weapon that kills other P. acnes strains without damaging skin. Weinstock says uncovering RT6’s strategy and the role it plays in skin health might eventually help researchers develop new treatments for acne.

May the good guys win

Currently, doctors use several types of medications to treat acne. Over-the-counter skin cleansers (such as Clearasil or Stridex) can help a mild outbreak. These products use chemicals to bring down swelling and slow bacterial growth. A doctor also may prescribe a medicine called a retinoid ointment. It uses a Vitamin A-type substance to open up the pores so that other medicines can get in. Still other treatments focus on controlling inflammation.

One promising alternative to antibiotics uses colored light, says Mishra. This approach, called photodynamic therapy, has become popular over the past decade. Researchers discovered that certain wavelengths of light would basically fry P. acnes bacteria. Ultraviolet light, a type of energetic light found in bright sunshine, works well to kill bacteria and clear up acne. But exposure to these powerful beams can damage the skin or even cause cancer. Blue-colored light is less energetic and safer. Yet it still destroys P. acnes bacteria.

Some dermatologists instead use lasers to target oil glands in an area of the skin that is prone to acne outbreaks. The laser light destroys some of the glands. This leads to a drop in sebum production, making acne outbreaks less likely to begin or worsen.

Some experimental acne medications introduce helpful bacteria to fight off harmful ones. This type of drug is known as a probiotic (PRO-by-OT-ik). Dermatologists are still working to develop and test probiotic treatments for acne. In one 2013 study, researchers at the University of Alberta in Edmonton looked at the effects of probiotics. They divided 45 acne-afflicted volunteers into three groups. One group received only an antibiotic, the second group only a probiotic, and the third group received both. After 12 weeks, everyone’s acne had improved. But the group that received both treatments had the clearest skin.

Future probiotics for acne could put good strains of P. acnes to work, Weinstock imagines. Teens might one day fight zits by transferring a strain such as RT6, from one part of the body to another. “Wouldn’t it be great,” he says, “if you could take some kind of adhesive tape, put it down on normal skin and pull it up, then put it on the acne and keep it there while you go to sleep?” The good bacteria would compete with any bad ones, and hopefully the good guys would win.

Teens using this approach could sleep while microbial battles raged on their faces beneath the adhesive tape. Good bacteria from healthy skin would fight for control of the pimply area. By morning, the good bacteria would have taken over. The tape could now come off, and the zits would gradually disappear. If it sounds too good to be true, it is — today. But a treatment like this might be on the horizon, thanks to the tiny bugs that call your face home.

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)