Two brain areas team up to make mental maps

While the hippocampus tracks where you are, the prefrontal cortex helps plan your route

We don’t always use a map or app to get around. Often, we rely on our brains to navigate. A new study shows which parts of the brain will participate in this.

clavivs/istockphoto

Following a map isn’t the only time people test their skills at navigation. We find routes all the time, whether it’s from one end of the house to another or to school and back. How does your brain get you to your destination? Two brain areas work together, a new study finds. One taps your memory to figure out where you are. Another uses that information to plan the path ahead. This discovery could help scientists one day design spaces for people who have difficulty finding their way.

The word “memory” makes people think of the past. But without it, no one could plan for the future. This is especially true in navigation, says Amir-Homayoun Javadi. He’s a neuroscientist — someone who studies the brain — at the University of Kent in Canterbury, England. He and his colleagues wanted to figure out how the brain finds different routes to a destination.

The scientists recruited 24 volunteers for a two-hour tour of Soho. It’s a neighborhood in London, England. Guides led the participants around, pointing out landmarks, book shops, cafes and other points of interest. These might help the volunteers later find their way. As they pointed things out, the guides also told the participants which direction they were facing — north, south, east or west.

One day later, the volunteers came to the lab and lay down inside a machine that does functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. This brain scanner tracks the flow of blood in the brain. That blood carries oxygen. If a part of the brain is very active, it will need more oxygen. So more blood will move toward it. Scientists therefore use blood flow as a way to pinpoint which brain areas are working hard during a task.

As the participants lay in the machine, they saw 10 videos of the neighborhood they toured the day before. In five of them, they “traveled” without having to find their own way. For the rest, they had to use a computer to navigate to a specific location. Sometimes, the scientists told them a route had been blocked. Now, instead of turning right, they might have to turn left. These detours forced the volunteers to use their memories to chart a new path to their destination.

The people remembered a lot from their tour, Javadi notes. On average, despite the road blocks they reached their destination more than 80 percent of the time. But Javadi didn’t care much about accuracy. While the volunteers navigated Soho, he and his colleagues were trying to determine which parts of the brain had been guiding them.

Traveling twosome

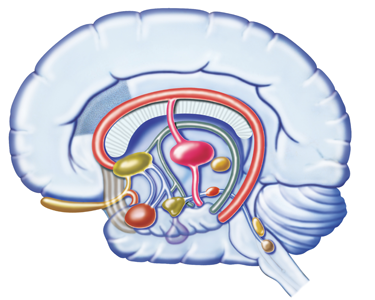

Two particular brain areas had been active in this pathfinding. The first was the right hippocampus. Each brain has two of these structures — one on either side of the head. Each forms a coil that curves up and back behind the ears. Hippocampi are important. Without them, new memories cannot form.

When participants were steering around the Soho video, they were sending a lot of blood to the posterior part of their right hippocampus. (Posterior means toward the back.) This part of the brain was especially active when the participants chose a new direction at an intersection. The right posterior hippocampus seemed to be keeping track of the change in the number of possible turns as someone moved from one intersection to the next. The first intersection may have allowed for many different turns, the next for only one or two, for instance. The hippocampus kept track of those differences in the number of options — and worked harder at intersections with many possible turns.

But how did people know which way to turn next? Here, the prefrontal cortex got involved. Just behind the forehead, this brain area helps with complex activities. Among them are making decisions.

This region also helps plan a future route, Javadi and his colleagues showed. When the volunteers had to find their way around roadblocks, the prefrontal cortex was more active. The hippocampus keeps track of where you are, but “the prefrontal cortex is one step ahead,” Javadi explains.

The team published its results March 21 in Nature Communications.

“It’s a fascinating study that breaks new ground in helping us understand how, and for what purposes, the hippocampus represents spatial information,” says Lynn Nadel. He’s a cognitive neuroscientist — someone who studies how the brain produces thoughts — at the University of Arizona in Tucson. The study especially helps to show how the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex work together when a person enters a new space, he notes. And it’s not just about finding our way, he adds. These brain areas also may be important for how our memories function.

The findings may help scientists understand more about our brains. But Javadi also hopes his work might help patients with diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, who may forget where they are. These patients can have a hard time remembering how to get home. Over time, they may even have difficulty getting around their own house. Javadi’s findings could help in the design of buildings and neighborhoods that are easier for those with memory problems to navigate.