The two faces of Mars

A single impact might explain why the Red Planet’s surface looks smoother in the north and rugged and rocky in the south

When you look up at the night sky, it’s hard to imagine the violent, chaotic place our solar system was billions of years ago. It looks quiet and peaceful now. But when the solar system first took shape, asteroids and other objects regularly slammed into each other. These could knock off huge chunks of rock, some that eventually became moons, and left the surfaces of the planets forever changed.

|

|

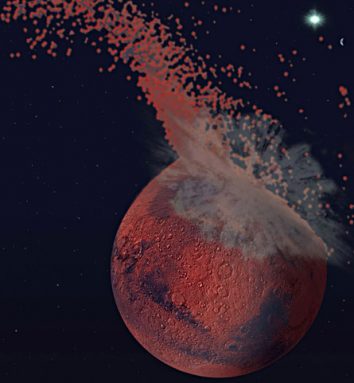

Mars may be home to the solar system’s largest impact crater, hidden below lava. The impact itself, illustrated here, may have given Mars its unusual “two faces” — af high, cratered crust in the southern hemisphere and smooth, low crust in the north. This illustration was created from Caltech simulations of the impact, one of three recent studies to support the idea that the uneven surface was created by a single impact.

|

| M. Marinova et al./Caltech |

Now, scientists say one of these massive collisions knocked off much of the top of Mars, our planetary neighbor. Their findings answer a question that has long puzzled scientists: Why do the Red Planet’s northern and southern hemispheres look so different from one another?

The debate started more than 30 years ago. That’s when NASA scientists launched the Viking spacecraft into orbit around Mars. The spacecraft sent back the first close-up maps and images anyone had ever seen of the Martian surface.

Surprisingly, those images showed that northern Mars looks very different from southern section of the planet. The north was flat and smooth. The south appeared rugged, dotted with craters and mountains. Another NASA spacecraft, the Mars Global Surveyor, later showed that the planet’s crust is also thicker in the south than in the north. In fact, the entire southern hemisphere of Mars is about four kilometers higher than the northern hemisphere.

What could account for these differences? It’s been a topic of debate for decades. Some suggested that processes deep below the planet’s surface gave Mars different kinds of crust in the two hemispheres. Others thought that over time the colliding meteorites, comets or other objects could have shaved off four kilometers of crust from the northern hemisphere. Still another pair of scientists suggested a single impact from just one object could have created the planet’s two faces.

By studying data from two spacecraft, NASA’s Mars Odyssey and the Mars Global Surveyor, a team of planetary scientists was able to look below the surface of a recent lava flow on the Martian surface. Just as on Earth, volcanoes periodically spew lava over the planet’s surface. And on Mars, this lava previously blocked scientists’ view of the planet’s underlying bedrock.

Below the lava, they found a huge crater the size of Asia, Australia and Europe combined. It runs the length of the boundary between the flat northern hemisphere and the bumpy southern hemisphere. It’s an important clue, scientists say.

“Finding this elliptical boundary is a smoking gun,” says Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna. He’s a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “There is only one known way to get a shape like this: impact.”

The impact theory gets even more support from additional findings from other scientists.

Two other groups of researchers used computer programs to predict what kind of impact could have given Mars its dual appearance. They ran a series of computerized scenarios in which they slammed different objects into the planet at different speeds and angles.

They estimated that a Pluto-sized object traveling at 32,000 kilometers per hour would have generated enough energy to blast off the crust of the planet’s northern half.

“Something big smacked into Mars and stripped half the crust off the planet,” says Francis Nimmo, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz who ran some of the computer simulations.

Steven Squyres is a planetary scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. These new observations still do not disprove the idea that processes deep below the planet’s surface could have caused the difference in the planet’s two halves, he says. But, he adds, “It’s nice to see an old idea dusted off and turned into something with real physical plausibility.”