Two Suns in the Sky

Some planets may orbit double stars, which means that the planets might have double sunrises and double sunsets.

By Emily Sohn

Sunsets can be beautiful to watch, but the pinks and purples of a fading Earth day might be boring compared with sunsets on planets outside our solar system. After all, we have only one sun in the sky. It now appears that some planets may have two.

Astronomers at the University of Arizona in Tucson have found evidence of planetlike objects around binary stars—pairs of stars that closely orbit each other. The new research suggests that there may be many worlds with sunsets far more spectacular than our own.

|

|

If this illustration looks familiar, perhaps you saw a similar image in Star Wars. In that movie, Luke Skywalker’s home planet, Tatooine, orbits a binary star system. A planet that orbits two stars could have a double sunset.

|

| NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (Spitzer Space Telescope) |

“This opens up the poetic possibility of life on planets in binary star systems where, when the sun rises or sets, it is not one star, but two stars going up and down,” says Alan Boss, an astronomer and theorist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, D.C.

The new discovery also greatly increases the number of places where scientists might find planets orbiting other stars. As many as 75 percent of sunlike stars in the Milky Way have at least one nearby companion star.

Scientists had long neglected binary- and multiple-star systems in their search for distant planets, because they are much more complicated to study than single stars. But now it appears that the extra work may pay off.

“The big splash from our work is that the number of potential sites for planetary-system formation has just gone up enormously,” says University of Arizona astronomer David Trilling, who led the research.

Star dust

Stars form out of huge clouds of gas and dust. The leftovers form a dusty disk around the new star. Within a few million years, some of the dust may clump and form asteroids and asteroid belts, comets, and even planets, all of which orbit the parent star. The rest of the dust gets blown out of the system.

|

|

Astronomers have found a solar system in which a dusty disk orbits a pair of stars. The disk might contain planets.

|

| NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle (Spitzer Space Telescope) |

Then, over the next few billion years, collisions between asteroids and other bodies produce new sprays of dust, which hover within the asteroid belt. When scientists detect a dusty disk around a star, it usually means that asteroids are there, crashing into each other and creating the dust.

Planets and asteroids form out of the same original stuff, so the presence of asteroids suggests that planets or planetlike objects are there too. At least 20 percent of stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way, have dusty disks around them, Trilling says.

No telescope is powerful enough to see a planet or an asteroid outside our solar system. However, telescopes can see the dusty disks around faraway stars. A disk indicates that asteroids and comets orbit a star.

Using various methods, scientists have found about 200 planets orbiting stars in recent years. About 50 of those planets are in binary star systems. But in every case, a vast distance—a distance much greater than the diameter of our entire solar system—separates the two stars. And all those planets orbit just one star, not a pair of stars.

If you could travel to one of those planets, one sun would look big in the sky, just as our sun does when viewed from Earth. The distant twin would simply look like another twinkling star.

Searching for a doubly sunny planet

Trilling and his colleagues wanted to find out whether planets formed around binary stars that lie close together. They used the Spitzer Space Telescope, which is in orbit around the Earth, to take pictures of 69 binary star systems. Some star pairs were as close to each other as Earth is to the sun. Others were farther away from each other than Neptune is from our sun.

|

|

An animated video (click here, or on image above, to watch) shows how a pair of stars might raise a family of planets.

|

|

NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle (Spitzer Space Telescope)

|

With telescopes that use visible light, scientists have trouble taking pictures of dusty disks because the stars are so much brighter than the dust. The particles of dust, however, absorb heat from the star and emit a type of energy called infrared light. Our eyes can’t see infrared light, but the Spitzer telescope can. In the images it produces, the dust looks much brighter than the stars.

Still, the researchers can’t usually tell what the pictures mean at first. “We see a fuzzy blob,” Trilling says.

But by calculating how much brighter a star with dust looks in the image than it would look without dust, astronomers get a sense of where the dust is within the binary system. Calculations also show how much dust there is. The calculations don’t show for sure whether planets are out there, but chances are high that at least some of these disks contain planets.

When the pictures from the binary study started arriving, the scientists at Arizona saw pretty much what they had expected. “At first, it was kind of a little bit ho-hum because we know that dust is out there around some stars,” Trilling says.

However, after the study ended and the scientists started to analyze their data, they found some surprises. Dusty disks, their results showed, are remarkably common around binary stars that lie close together.

|

|

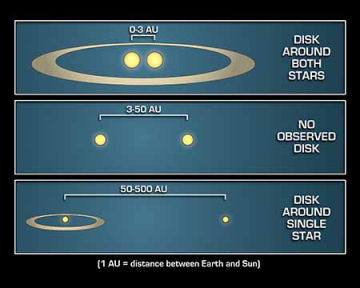

Dusty disks are common around binary stars that lie close together (top). Disks either don’t exist (middle) or orbit only one of the two stars (bottom) when the stars are far apart.

|

| NASA/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle (Spitzer Space Telescope) |

“The number of these stars that have this dust is much, much higher than we expected,” Trilling says. Binary stars that are close to each other have far more dusty disks around them than do single stars or binary stars that are distant from each other, he adds.

That discovery suggests that close binary stars may be the best places of all to look for planets and for life on other planets.

The finding is also forcing scientists to reconsider long-held assumptions about how and where planets form. It is not yet clear, for example, why dusty disks are so common in close binary systems.

“The theory is totally up in the air,” Trilling says. “Nobody knows.”

Life under two suns

Scientists still have doubts about how a binary-orbiting planet forms. But one thing is sure: Life on such a planet would be interesting. Every day, one sun would appear to chase the other across the sky. The suns would rise and set just minutes apart. Sometimes, one sun might dip behind the other, affecting the amount of light and heat on the planet’s surface.

“It would be a weird place to grow up,” Boss says. “Every day would be different.”

And with more suns in the sky, he adds, any intelligent creatures on these planets would have at least double the opportunities to become fascinated with astronomy.