Under Antarctic ice, microbes gobble up greenhouse gas

Bacteria break down the powerful methane before it can reach the atmosphere

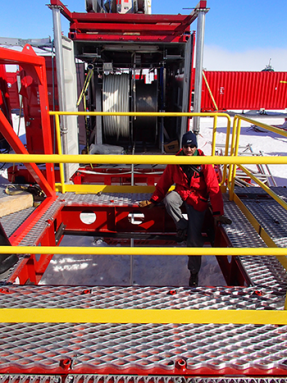

In a lake beneath an Antarctic ice sheet like this one, scientists have found bacteria that eat methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

Elaine Hood, National Science Foundation

By Ilima Loomis

Trapped beneath blankets of ice in Antarctica are huge amounts of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. Scientists have long feared that climate change will melt these ice sheets and release the climate-altering gas. But a new study suggests the threat might not be as bad as it seemed. That’s thanks to some microscopic helpers: bacteria.

“In nature, one bug’s poison is another bug’s food,” says study coauthor John Priscu. He’s a polar ecologist at the Montana State University in Bozeman. He specializes in microbes in ice. He and his team have now turned up bacteria eating methane deep beneath the ice there, at the bottom of the world. And he suspects they’re hungry enough to gobble all of it up before it can escape into the air.

Millions of years ago, sea levels were higher. This left an ocean covering Antarctica. When sea levels dropped and the ocean retreated, it left behind a layer of debris from plant and animal life. As global temperatures cooled, a thick sheet of ice gradually formed. Years went by. Eventually, bacteria under the ice broke down the organic material. And they exhaled methane.

That’s what scientists believed, anyway. “No one ever measured it. It’s very difficult to get to the bottom of the Antarctic ice sheet,” Priscu explains. So his group set out to do just that.

Four years ago, they drilled down more than 800 meters (about half a mile) through the ice. Then they scooped up samples of water and sediment from the lake below. This Lake Whillans is known as a subglacial lake, or a body of water that sits far below some ancient blanket of ice. That’s what scientists believed, anyway. “No one ever measured it. It’s very difficult to get to the bottom of the Antarctic ice sheet,” Priscu points out.

Analyses of those lake samples now confirm for the first time what scientists had long suspected. “Yep, there is methane,” Priscu says. And the methane’s chemical makeup confirmed that it came from bacteria eating ancient organic material.

But the scientists also found something they hadn’t expected. “There’s another group of organisms, and it is eating the methane,” Priscu reports. These bacteria digest methane and release carbon dioxide (CO2). Yes, CO2 is also a greenhouse gas. But it’s a far weaker one (methane is around 30 times more powerful than CO2) — and plants can soak up the CO2.

The team published its findings online July 31 in Nature Geoscience.

Methane munchers on Earth and beyond

David Karl says the new findings are important. A microbiologist, he works at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Karl says the new data offer the first direct evidence that there’s life in these subglacial lakes.

The scientists showed that methane is forming in sediment at the bottom of the lake. “But, voila, when they go and look for [methane in the water] it’s not there,” Karl says. The team used genetics, modeling, geochemistry and other sciences to show that the methane disappears because microbes are eating it. The methane eaters seem to be totally canceling out the methane producers — at least in this lake.

These data are good news for climate scientists. Some have feared that methane released by melting ice could make climate change much worse. But this suggests that bacteria could eat the methane before it ever enters the air. Sites similar to Lake Whillans exist across Antarctica. So Priscu thinks it’s likely that these methane-eating bugs are widespread.

The new findings also could prove of great interest to scientists who look for life on other planets. Conditions in Antarctica are similar to those on icy worlds in our solar system, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa. Studying how microbes grow in extreme habitats such as subglacial lakes gives scientists an idea of what life might look like on these other planets. It’s also a chance to develop tools that could come in handy on future space missions.

To get through the ice covering Lake Whillans, the scientists had to invent a new hot-water drill. “Think of a giant garden hose with a 12-foot-long nozzle at the end that blasts out almost-boiling water,” Priscu says.

Scientists used melted glacier water to drill through the ice. But first they sterilized the water. They needed to make sure that no surface germs could infect their samples or the delicate ecosystem under the ice.

It took 12 tractors to haul more than 450,000 kilograms (a million pounds) of gear on sleds 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) to the research site. Fifty-two scientists, engineers, and other crew members camped in tents on the glacier for two weeks. They worked around the clock to drill through the ice and collect the samples. But Priscu says it was worth it.

“We know more about the surface of the moon than we know about the Antarctic continent,” he says. “Every time I go down there, I’m overwhelmed by questions.”