There’s a real upside to knowing you could be wrong

Understanding the limits of your beliefs can make you a better student

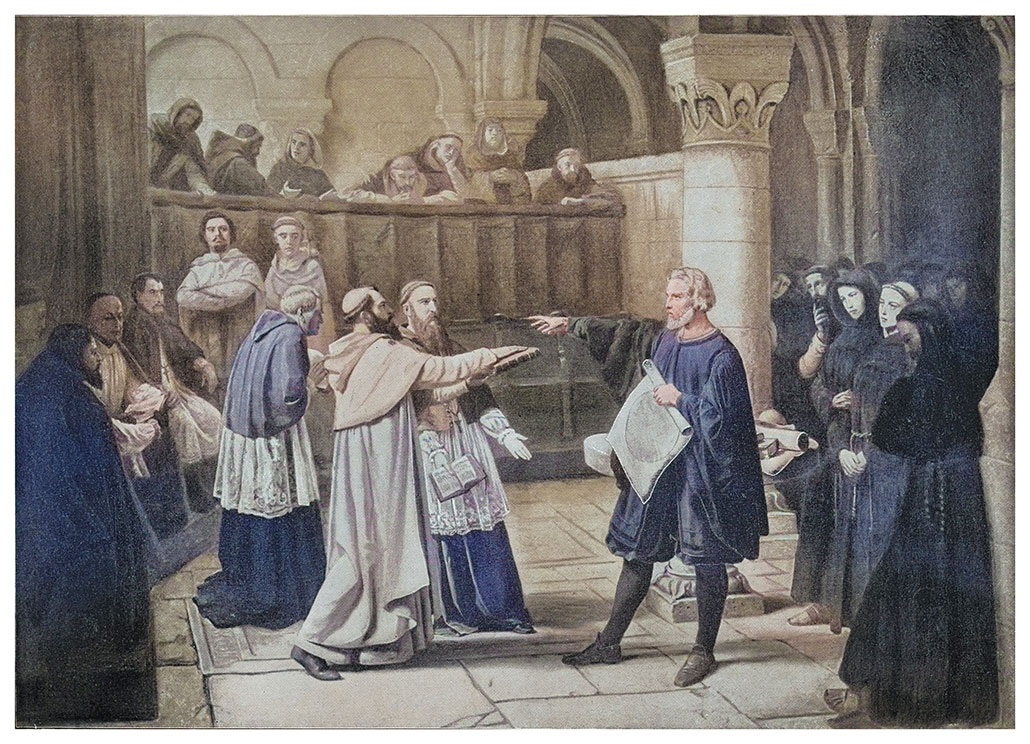

In Galileo Galilei’s time, the church and scientists thought everything in the cosmos revolved around Earth. Galileo’s observations proved that view wrong and advanced science — but won him house arrest for the rest of his life.

Hulton Archive/Stringer/Getty Images; adapted by L. Steenblik Hwang

By Jane Palmer

Growing up in the 1570s, Galileo Galilei believed what everyone “knew” to be true at the time: that Earth was the center of the universe.

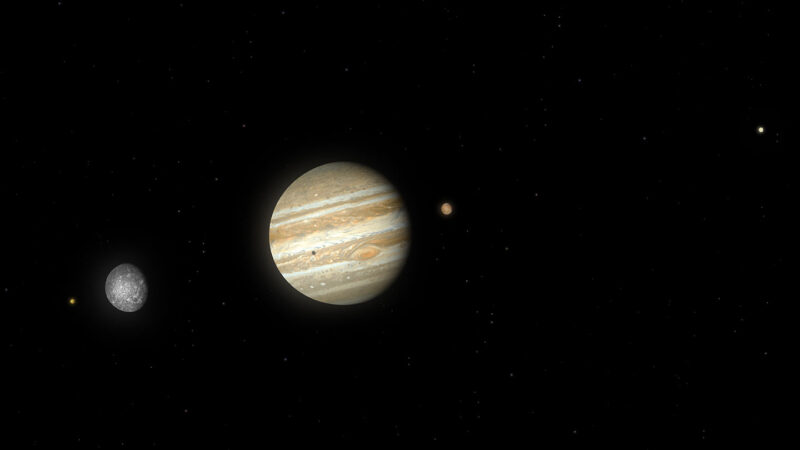

He went on to train as a mathematician. And in 1609, he built one of the first telescopes able to resolve details of celestial objects. He started by peering at the moon. The next January 7, he spotted what looked like four stars close to Jupiter. He kept spying on them and drawing them. Over time, however, he noticed something strange: Each star’s distance from Jupiter seemed to be rapidly changing.

Eventually, Galileo realized that these objects — celestial bodies that would later be known as moons — were circling Jupiter. This discovery caused him to begin questioning his beliefs. The Catholic Church had taught him that Earth was the center of the universe and that everything else merely moved around it. So how could those four star-like objects be spinning around Jupiter instead?

After many more nightly viewings and drawings, Galileo came to conclude that the sun was actually the center of the universe. This meant that Earth and other planets rotated around the sun. This idea made him very unpopular. In 1616, the Catholic Church put Galileo on trial. Its leaders pointed out that his newfound belief contradicted the Bible. The costs of this belief: The church convicted the scientist of heresy and sentenced him to house arrest for the remainder of his life.

None of this changed Galileo’s mind. And with time, his theory would become a basis for helping scientists understand the universe (although others would show the sun was the center of our solar system, not of the entire cosmos). Galileo also made other important discoveries. For such achievements, Albert Einstein referred to Galileo as the “father of modern physics — indeed, of modern science altogether.”

Scientists now point to one factor that may have contributed to Galileo’s scientific success: his ability to challenge his own beliefs and admit they might be wrong.

For many years, Mark Leary has studied the role of people’s beliefs in their behavior. Leary is a neuroscientist at Duke University in Durham, N.C. Admitting you could be wrong can lead you to pay more attention to any evidence you encounter, he’s found. That’s what Galileo did.

Galileo “wasn’t just the right person against the wrong establishment,” Leary says. In fact, he started out “as wrong as everyone else at the time.” But then, Leary notes, Galileo “suddenly realizes: ‘Oh man, I was wrong!’”

Tenelle Porter works at Ball State University in Muncie, Ind. As an educational psychologist, she’s asked students to rate the degree to which they tend to question their own beliefs. She’s essentially gauging how humble they are in their thinking.

“Knowing our beliefs could be wrong helps us in a few ways,” Porter says. “For example, if we can recognize that our ideas about something might be wrong, we’re more likely to do what it takes to get them right.”

Being humble, such work has shown, is an overlooked learning superpower.

Avoiding overconfidence

Self-confidence is trusting in our abilities or qualities. It’s usually seen as a good thing. But most of us might benefit from a little less confidence in our beliefs.

For instance, Leary asked a sample of adults to think back on recent disagreements. On average, he asked them, how often had their positions been the ones in the right? You’d expect them to say they were right about half the time. Instead, a whopping 82 percent — more than four in every five — said they were right more than half the time. That suggests they were overconfident. They had likely overestimated their knowledge and how sound their beliefs were.

Scott Plous believes such overconfidence is very common, especially when it comes to what people believe to be true. A psychologist, Plous works at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn. And overconfidence, he says, can lead us to catastrophic decisions. In 1986, for example, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) believed that the risk of loss for any single space-shuttle flight was roughly one-in-100,000. It was an overconfident belief and might have led to the explosion that year of the Space Shuttle Challenger.

The good news, he adds, is that there’s a “vaccine” for overconfidence. And that’s recognizing that your beliefs could be wrong. Scientists have a fancy term for this. They call it “intellectual humility.” And it can help you in many ways.

This way of thinking, Leary says, is like having a little wise friend on your shoulder asking you to consider whether you could be wrong about a belief. In contrast, overconfidence is like having a not-so-good friend on your shoulder who’s always telling you that you’re right and everyone else is wrong.

To benefit from intellectual humility, Leary says, you may not need to change your mind about something. It’s more about just being open to the idea that what you believe might be in error. “You are not throwing your belief out the window,” he says. “You are just double checking.”

Elizabeth Krumrei-Mancuso is a research psychologist at Pepperdine University in Malibu, Calif. She asked 144 college students to complete a survey to gauge their intellectual humility. It gave them statements that they could check or uncheck. Examples included: “I am willing to change my mind once it’s made up about an important topic.” Or “When I am really confident about a belief there is little chance that belief is wrong.” The survey also measured how curious students were and how much they liked challenging, intellectual tasks.

Students who saw that their thinking could be fallible, or flawed, tended to be more curious, this study found. They also were motivated to seek out new knowledge. Because these students were aware they might be wrong, they hunted out new information, Krumrei-Mancuso says. “So, they end up knowing more at the end of the day.”

Krumrei-Mancuso and her team shared these findings in The Journal of Positive Psychology.

The opposite is also true, her data suggest: “If you don’t think that you’ve got anything in your worldview that needs analysis or correction, why would you even look at it?” And that, she says, is an attitude that can really harm your ability to learn or to acquire knowledge about the world.

In short, Leary says it pays to be humble and open to the idea that your beliefs could be wrong.

“Smart people are smart enough to know that they don’t know everything.” And, he adds, “They’re smart enough to know that some of the stuff they think they know will eventually turn out to be wrong. That’s part of being smart.”

Learning to study smarter

Knowing you could be wrong can lead you to seek — and ultimately collect — more accurate knowledge. But does it actually help you beyond that? To find out more, Porter at Ball State conducted a series of studies with high-school students.

She started off by asking 103 of them to rate themselves on statements like: “I am willing to admit it when I don’t know something.” Or “I acknowledge when someone knows more than me about a subject.” Or “I try to reflect on my weaknesses in order to develop my intelligence.” Then she started measuring what education psychologists refer to as “mastery behaviors” — skills that students can use to master their material.

Students who could see that their beliefs might be wrong were much more likely to use strategies to test their knowledge while they were studying, this study found. These kids would quiz themselves. They’d check to see that they really understood the material. And they’d seek out potential holes in their understanding.

Students who didn’t see that their knowledge could be flawed might instead just sail through their studying, Porter says. They won’t stop to ask themselves if they truly understand what they read, heard or did.

Such students, she found, can fall prey to a “knowledge illusion.” This is where they think they’ve got a subject down pat. “But that illusion is punctured very quickly when you’re asked to explain it on a test,” she points out. Only then does it become “very clear that you don’t actually understand as much as you thought that you did.”

Students who knew their beliefs could be wrong used skills that helped them in studying and test-taking, her team found.

But how did these students react when they got test scores back? To find out, Porter recruited 88 high-school freshmen and sophomores. All had the same math teacher.

Three months into their classes, Porter gave them the same questions as the previous study to rate how much they questioned their beliefs. Four months later, after their teacher had graded a test, Porter passed out another questionnaire to see how the students were reacting to their test grades.

This questionnaire had statements like “For my next test, I will try to determine what I don’t understand well.” The questions also gauged the students’ persistence after the test. It asked them things like whether they “will give up studying” or “only study the easy parts.”

Teens who could see their beliefs might be wrong said they’d change their study strategies. Going forward, they’d determine how to improve their performance and master the material for the next test. These students appeared to be more persistent than the others.

But these students weren’t just going to “try, try and try again” in some mindless way, Porter adds. They said they’d be taking an honest look at what they’d done wrong and try to figure out how to avoid that next time.

The students who questioned their beliefs also ended up with higher grades in math. Porter shared her team’s 2020 findings in Learning and Individual Differences.

“There’s not a person out there that doesn’t run into failure,” Porter says. “But really, the only way to get better is by persisting and learning from your failures.”

Baby steps

Although it might be good for you, researchers recognize that questioning your beliefs can be truly hard. Nobody wants to be wrong. Few of us even want to think about being wrong.

Our beliefs can act as a security blanket. They can help us feel safe and certain. And we may not want to lose that feeling. Still, it’s important to remember that questioning beliefs isn’t always about swapping old ones out for new ones.

“We don’t change our beliefs willy-nilly,” Krumrei-Mancuso says. It’s more about being open to considering new evidence.

It can help to think of where you may do this already. In cooking, for example, people regularly experiment with a recipe. Would it taste better with a little more sugar — or maybe a little less? Perhaps it should bake for less time? Similarly, to get better at shooting hoops you would try new approaches and see what works. What if you hold the ball differently? Or aim higher above the basket’s rim?

“We do this in a lot of domains very naturally. It’s not a bad thing to keep checking,” Leary says. “But for some reason, people think there is something wrong with checking their beliefs.” Leary suggests that people view their questioning of beliefs as a helpful habit. People get in habits of challenging themselves or following celebrities on Instagram. Questioning beliefs, he says, can simply be a new habit.

Leary cautions against trying to do this every single time you make a decision. That would become exhausting, he says. Practice it when you’re thinking about whether something is correct or making some really important decision. This might prove most beneficial when you feel really strongly about something, Leary says. “Ask yourself: Am I certain I am right about this?”

If you find it hard to question a belief, try taking “baby steps,” he says. Start looking at why you hold that belief. See if the reasons you do make sense. Think about who you may have gotten a belief from, for example. Then ask that person how sure they are that they’re correct — and what convinced them. Or ask yourself why you might want to hold some belief. Does it help you feel safe or fit in? Scientists before Galileo may not have wanted to question whether the Earth was the center of the universe — perhaps because they were worried what might happen to them. (And with good reason, it turns out.)

Galileo suffered for changing his beliefs. But today, questioning beliefs can bring benefits in the classroom and beyond. And even for Galileo, there was an upside. By changing his beliefs, he shined a light on an exciting “new” universe to investigate with his research. Similarly, checking your beliefs can open up your world and stops it from narrowing, Porter says. “You get to discover something new,” Porter says. “It’s such an adventure.”

Travel and research funding for this story was provided by University of California Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center as part of its “Expanding Awareness of the Science of Intellectual Humility” initiative, which is supported by the John Templeton Foundation.