Rock rising from below the Atlantic may drive continents apart

If true, plate tectonics at mid-ocean ridges may be more push than pull

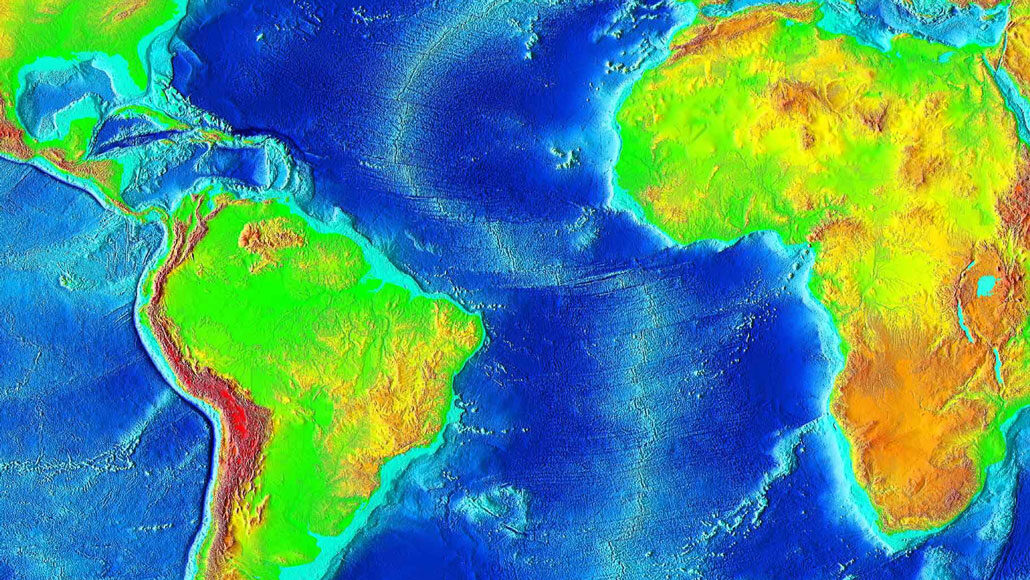

Material rising from deep below the Mid-Atlantic Ridge may widen the ocean by a few centimeters every year. The ridge is visible in this false-color map as a light blue line through the Atlantic.

NOAA

Hot rock surging from deep beneath the Atlantic Ocean may be driving the continents on either side apart. That’s the finding of a new study.

Each year, the Americas get a few centimeters farther away from Europe and Africa. The tectonic plates underlying those continents are drifting apart. Researchers thought most of this plate movement was driven by the far edges.

Those distant edges were thought to be sinking down into Earth’s mantle. That would pull the plates apart, creating a gap. Material from the upper mantle could then seep up through the rift between the plates. As it hardened, it would fill in the seafloor. And the ocean would become just a bit wider.

But seismic data from the Atlantic Ocean floor now challenges that idea.

Hot rock is welling up from hundreds of kilometers deep in Earth’s mantle. It is rising up under a seafloor rift called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. And it doesn’t look like a passive flow pulled up by tectonic plates sliding apart. Rather, the deep rock is pushing forcefully toward Earth’s surface. So it seems to be driving a wedge between the plates that helps separate them. Researchers reported this online January 27 in Nature.

Their finding could change scientists’ understanding of plate tectonics. This process causes earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. More knowledge about how plates shift could help people better prepare for these natural disasters.

Matthew Agius is a seismologist at Roma Tre University in Rome, Italy. Seismometers measure seismic waves triggered by earthquakes. Agius and his colleagues installed 39 of these devices on the Atlantic seafloor. They chose a spot along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between South America and Africa. Those sensors let the team glimpse what’s happening beneath the seafloor. For about a year, they monitored rumbles from earthquakes around the world. Their seismic waves traveled deep through Earth’s mantle on their way to the seismometers. The tremors they picked up contained clues about the location and movement of material far below the seafloor.

In those signals, Agius’ team saw hints of deep movement. It came from more than 600 kilometers (375 miles) down. Material from Earth’s lower mantle was welling up toward the ridge. “This was completely unexpected,” Agius says. The flowing rock could be a powerful force for pushing apart the tectonic plates on either side of the rift.

Jeroen Ritsema was not involved in the work. He is, however, is a seismologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He says of the new seismic data, “It’s certainly an interesting observation.” But it’s from only one group of seismometers near the equator, he points out. From that, he says, it’s hard to tell how widespread the effect might be. They don’t yet know what’s going on elsewhere along the ridge. It’s like “you’re looking through a keyhole,” he says. “And you’re trying to see what’s in the living room and the bedroom and the kitchen.”

Observations at more spots along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge could fill in the gaps. They might help show how much upwelling of the deep mantle drives a spreading of the Atlantic seafloor. Data from other mid-ocean ridges around the world would also be interesting. That could show if upwellings are driving other continents apart too.