Urchin mobs can literally dis-arm a predator

The spiny urchins pin the arms of a starfish in dramatic turnabout of who is the prey

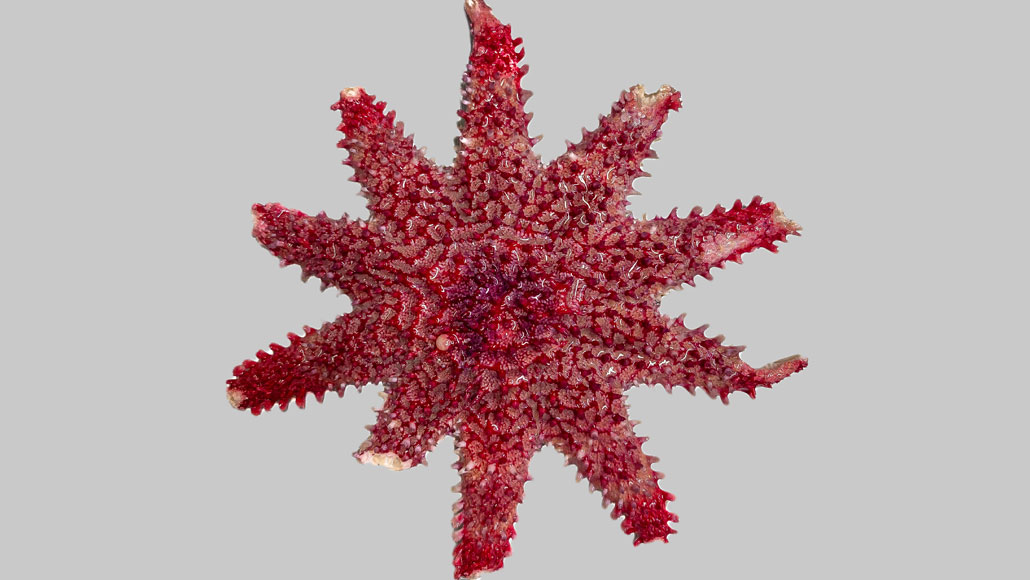

A common sun star (Crossaster papposus), seen here, was found mangled in an aquarium. In a classic reversal of predator and prey, it had been attacked by dozens of starving sea urchins.

Jeff Clements

By Jake Buehler

Sea urchins are underwater lawnmowers. Their never-ending appetites can alter whole coastal ecosystems. Normally they eat algae and other underwater greenery. But these spiny invertebrates also will take a bite of something more meaty — and dangerous. That’s the surprise finding of a new study.

In a first, researchers have seen urchins attacking and eating predatory sea stars. Normally starfish are the predators. Researchers describe this unexpected flip on who eats who in the June issue of Ethology.

Jeff Clements is a marine behavioral ecologist. He now works for Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Moncton. But back in 2018 he worked at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. For one project, he became part a team studying common sun stars in Sweden. At some point, Clements needed to separate one of the sun stars for a short while. So he placed it in an aquarium that already housed some 80 green sea urchins.

Starfish “are predators of urchins,” he recalls thinking. “Nothing’s gonna happen.’” But the urchins (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis) hadn’t eaten a bite in two weeks. When Clements came back to the tank the next day, the sun star (Crossaster papposus) was nowhere to be seen. A group of urchins were piled on the side of the tank. Below them was something red. It was barely visible. When Clements pried the urchins off, he found the remains of the starfish.

“The urchins had just ripped it apart,” he says.

No fluke

Clements and his colleagues realized no one had ever described this urchin behavior. To test whether it was a freak occurrence, the team ran two trials. Each time, they placed a single sun star in the urchin tank. Then they watched.

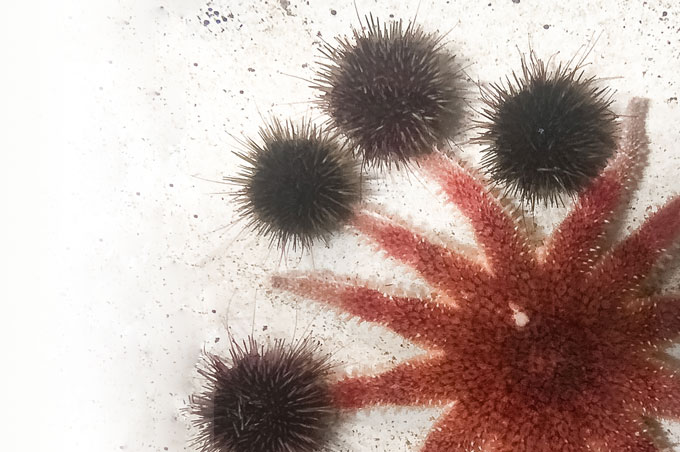

One urchin would approach the starfish. It would feel around. Eventually it attached itself to one of the sun star’s many arms. Other urchins would soon do the same. They quickly covered the sun star’s arms. When the team removed the urchins after about an hour, they found tips of the starfish’s arms had been chewed off. So had its eyes and other sensory organs that reside on those arms.

This aspect of the sun star’s anatomy may pose a risk.

“[The tips] are the first part of the sun star that the urchin is going to encounter as it approaches,” explains Clements. “So if the urchin consumes those first, the sun star is going to be less effective at escaping the attacks.”

The team calls this tactic “urchin pinning.”

Do urchins play defense or offense

It’s possible the urchins are acting in self-defense. They may be disarming — literally — a predator in their midst. But the urchins’ hunger might also explain their attacks, says Julie Schram. She’s an animal physiologist at the University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau. In crowded lab conditions with limited food, urchins can switch up their diet in surprising ways, she notes. Some species, for instance, have been seen cannibalizing each other.

“This would suggest to me that when starved, adult urchins will seek out alternate food sources,” she says.

The urchins’ capacity to feed on predatory sea stars had been hinted at before. Sea stars have turned up in urchin stomachs, notes Jason Hodin. He’s a marine biologist at the University of Washington in Friday Harbor. But this dining turnabout often was interpreted as scavenging. For instance, the urchins might have just finished off the remains of someone else’s dinner.

Actively attacking starfish for dinner is a “more interesting possibility,” he says. And, he adds, “It’s satisfying to see that possibility confirmed, at least in the lab.”

If urchin attacks also occur in the wild, Clements thinks there could be some interesting impacts on kelp forests. When overabundant, urchins can overgraze kelp forests, leaving behind “barrens.” If urchins are able to survive by eating other animals, they may not die off when the kelp is gone. This could keep urchin numbers high and “delay the recovery of these kelp forests,” says Clements.

Such discussions are premature, argues Megan Dethier. Such ideas are making way too much out of a “peculiar lab situation,” says this marine ecologist. She works at the University of Washington Friday Harbor Laboratories. After all, Dethier notes, such attacks haven’t been documented even in urchin barrens, where food is scarce,

And the urchin attacks can’t be intentional, she adds, since the animals don’t have a brain or central nervous system. It makes no sense, she says, that urchins could mount “a coordinated predatory attack.”

Such mob attacks may be based on chemicals released into the water by feeding, Clements counters. Once the first urchin starts chewing on a starfish, the other urchins may start recognizing the chemical scent of sea stars as food. Clements wants to run new tests to see what levels of hunger and crowding density might affect urchin appetites for sun stars.