Warning: Climate change can harm your health

Low-income people and vulnerable groups will be hit the hardest

In March, Cyclone Idai struck Mozambique, causing widespread flooding. It also sparked an outbreak of cholera.

Climate Centre/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

This is the ninth in a 10-part series about the ongoing global impacts of climate change. These stories will look at the current effects of a changing planet, what the emerging science suggests is behind those changes and what we all can do to adapt to them.

The city of Beira was overwhelmed when Cyclone Idai slammed into Mozambique on March 14 and 15. Floods swept across 3,000 square kilometers (1,200 square miles) of the nation. The area affected was about three-quarters the size of the state of Delaware. Homes were inundated. Roads and bridges washed away. More than 1,000 people died in this country, Malawi and Zimbabwe. The full death toll may never be known.

The waters laid waste to crops in areas around Beira. This set the stage for hunger. Floods shut down much of the city’s water and sanitation systems. The threat of waterborne disease loomed.

As of April 10, Mozambique’s health officials said more than 4,000 people had been infected with cholera. Bacteria in contaminated water cause this disease. Its symptoms include severe diarrhea, violent vomiting and dehydration. People who don’t get prompt treatment can die. Clearly, the country faced a major health crisis.

Scientists can’t yet say exactly what role climate change may have played in Cyclone Idai. But they do know that extreme storms will become more common with climate change. They know, too, that low-income countries in Africa and elsewhere will be hit harder than more well-to-do nations. And they know that there will be a wide range of health impacts — including more waterborne disease.

Climate change is acting in many ways that can harm health. Between 2030 and 2050, a quarter million more people will die each year than would if climate change were not a factor, the World Health Organization now predicts. And this estimate may be low. It doesn’t include all the many ways that climate change can affect health.

We don’t have to wait until 2030 to see impacts, either, says Kristie Ebi. She’s a public health expert at the University of Washington in Seattle. “Climate change is already affecting our health,” she notes.

Extreme heat is one problem. More intense hurricanes, rainstorms and wildfires are others. Such events cause direct harm. They also can disrupt basic health services and promote the spread of disease. But climate change will alter the planet in less obvious ways that can harm health. Air and water pollution will worsen in many places. Infectious diseases will become more common at some sites, or spread to new ones.

The more scientists and engineers learn about climate change and its impacts, the better people will be ready to deal with them. “If we understand that we are part of the cause, it gives some hope that we can be a part of the solution,” says Sarah Kew. She’s a climate scientist with Vrije University Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Muddy waters

Cyclone Idai was just the latest in a series of devastating storms, many of which have been intensified by climate change. Last September in the United States, for instance, Hurricane Florence flooded huge areas of North Carolina. The waters swept sewage, fertilizers, animal waste, coal ash and animal carcasses into waterways. Floodwaters also messed with water-treatment plants and sewage systems. Water systems shut down in about two dozen communities. Another 20 or so warned their residents to boil their water before use.

Climate change threatens water supplies in other ways, too. Storms can bring contamination. Sea level rise can overwhelm sewer pipes and treatment plants, sweeping more contamination into waterways. Droughts can take away once abundant water supplies.

Blooms of harmful algae happen when some single-celled species grow out of control. Some of them make poisons that cause breathing problems. Others algal toxins can harm the liver, damage the nervous system or affect the brain (and memories).

A bad bloom in Lake Erie forced the city of Toledo, Ohio, to shut down its water system for two days in 2014. Climate change will likely bring more bad blooms. One way they can do this: Climate-intensified storms can wash more fertilizer into waterways. Those nutrients can feed toxic algal species in lakes and along coastlines. Warmer waters also are expanding the areas where algal blooms are likely to emerge.

Christopher Gobler is a coastal ecologist at Stony Brook University in New York. He and other scientists found that since 1982, the niche for harmful algal blooms had grown in the northern Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The timing of when blooms might erupt could shift as well. The group reported its findings in 2017 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Water is the primary medium through which we will feel the effects of climate change,” reports UN-Water, a United Nations agency. Water supplies, water cleanliness and water-delivery systems are all at risk. Yet the health impacts of climate change don’t stop there.

Turning up the heat

In folklore, Lucifer is a name for the devil. But in 2017, Lucifer took on an extra meaning. It was the name given to a heat wave that made many people think about fires in hell. In parts of southern Europe that August, temperatures topped 40° Celsius (104° Fahrenheit). Even at night, those hot spots didn’t dip below 30 °C (86 °F). So public health officials issued warnings. Find cooler shelter, they said. Limit physical activity. Drink extra fluids. Their concern: Heat can kill.

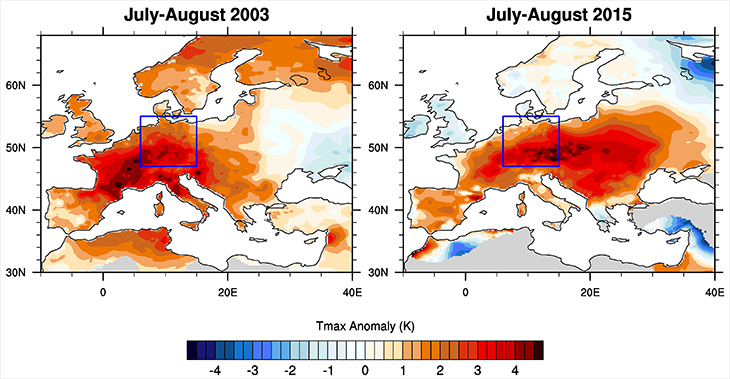

Lucifer-like heat waves were once rare. Now, southern Europe can expect them about once every 10 years. “We estimate that human-caused climate change has increased the odds of such an event more than threefold since 1950,” says Kew. She led the study behind that forecast.

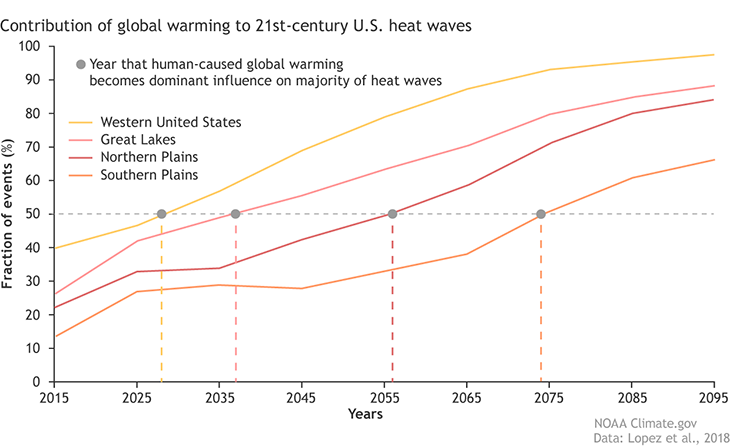

There’s a similar forecast for the United States. Hosmay Lopez is a climate scientist in Florida with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Miami. “Without human influence, half of the extreme heat waves projected to occur in the future wouldn’t happen” in most of the United States, he says. And by human influence, he’s referring to the burning of fossil fuels and other activities that have been playing a role in warming Earth’s climate.

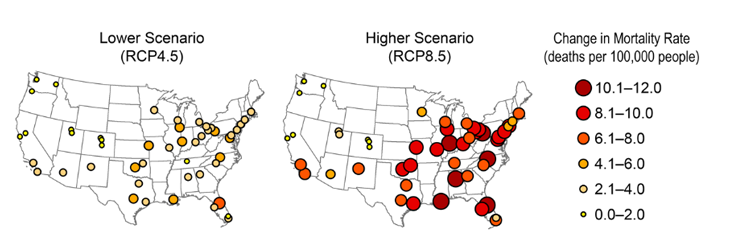

An increased risk of death from heat waves exists worldwide, says Yuming Guo. As a biostatistician, he’s a numbers man. He’s also an epidemiologist — a disease detective — at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. He and other scientists calculated the added risks for heat-wave deaths in 20 countries and regions. They compared the risks that have been forecast to occur between 2031 and 2080 to those seen between 1971 and 2020.

In general, poorer countries in warm regions will be hit hardest, they found. If people do nothing about climate change, for example, Colombia in South America could have roughly 20 times more deaths from heat waves. Moldova in Eastern Europe would have about 50 percent more deaths. The team shared its results in PLOS Medicine on July 31, 2018.

“Climate change affects all of us,” Madeleine Thomson says, “except some of us have a lot more resources [money and experts] to be able to tackle it.” She’s an insect biologist and environmental health scientist at Columbia University in New York City.

Not breathing easy

Climate change isn’t just warming the air. It’s also making that air harder to breathe for many people. Some of the reasons include rising levels of pollen, pollution and other air quality problems.

Plant pollen can cause hay fever. Its misery includes sneezes, runny noses, sore throats, headaches and itchy eyes. Pollen also can trigger asthma attacks, making it hard to take a breath. Climate change may lengthen the growing season for the pesky sources of pollen in many areas. Higher levels of carbon dioxide may also promote more plant growth.

“I personally suffer from spring-time allergies and fear a longer and potentially worse pollen season,” says Michael Case. He’s a climate scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle. Case and ecologist Kristina Stinson looked at how sneeze zones for ragweed pollen could shift in the eastern United States. She works in Massachusetts at the University of Amherst. The duo shared their work in PLOS ONE on October 31, 2018.

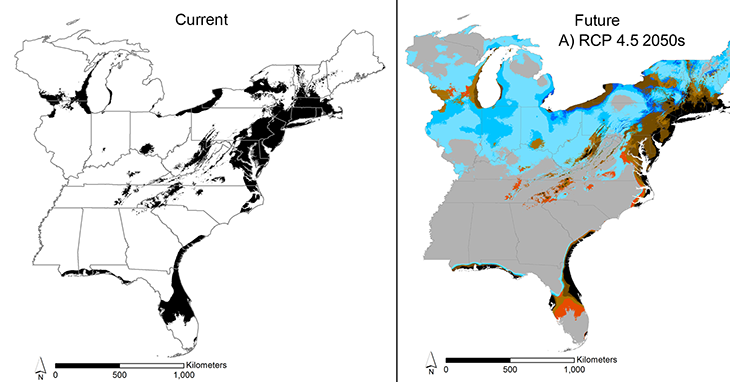

Climate change will bring warming and a shift in rainfall patterns. That will push ragweed farther north into new places, such as the northeastern United States. The plant also could spread northwest into Wisconsin, Minnesota and Canada. Meanwhile, parts of Florida and the Appalachian mountains may become less ragweed-friendly. “These changes will have real effects on people’s health,” Case says, “making it worse in some areas and potentially better in other areas.”

Trees, too, can trigger allergies and asthma. Patrick Kinney is an epidemiologist at Boston University in Massachusetts. He was part of a team that looked at how changes in when oak trees release their pollen will affect asthma sufferers in the eastern United States. Oak pollen led to 21,000 emergency room trips there for asthma in 2010. Severe climate change could up that by another 5 to 10 percent by 2050 to 2090, the team reported in the May 2017 issue of GeoHealth.

A bigger concern, though, may be pollution. Last year Kinney looked into research on the interactions of climate change, pollution and health. Burning of fossil fuels and other activities release chemicals called nitrous oxides and volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. Sunlight triggers chemical reactions in both types of chemicals. That brews up ground-level ozone. And ozone is a trigger for asthma attacks and other breathing problems.

“VOC emissions go up as the temperature goes up,” Kinney notes. “And that promotes ozone formation because there’s more of that stuff” in the air. Also, people will need more air conditioning during hot spells. But burning fossil fuels to make electricity will end up releasing even more ozone-forming chemicals.

The burning of fossil fuels also fills the air with teeny, tiny pollutant particles. More of these particulates can form as sunlight breaks down other air pollutants. Particulate pollution can cause lung disease. But that’s not all. “There’s all sorts of gunk in the particles that gets absorbed into the bloodstream,” Kinney notes. Studies show those tiny bits can cause heart and circulation problems. They also may mess with hormone levels and some brain functions. Kinney shared his findings in the March 2018 Current Environmental Health Reports.

Wildfires spew particulates, too, along with other pollutants. Bad air quality affected vast areas of the western United States, where wildfires raged last year. And there are more to come. From 2046 to 2051, 440 western U.S. counties will have at least one high-pollution smoke day. The total 5-year increase across all those counties: almost 5,000 more high-smoke days than had plagued them during the 5-year span of 2004 to 2009. That’s because bigger fires will affect multiple counties. So concludes a 2016 study in Environmental Research Letters.

Even droughts can make breathing harder. Dry spells make the ground dusty. Winds can kick that dust into the air. Breathing it in can irritate lungs. Dry soil also kick-starts the growth of a harmful fungus. It causes a disease commonly known as valley fever. A team of scientists found a link between the number of valley fever cases in California and Arizona and soil-moisture levels the fall and winter before. Their report was in GeoHealth in 2017.

Dealing with disease

Scientists describe an organism that can spread disease as a vector. Insects, ticks and various other animals can be culprits. Climate change will affect where such vectors thrive, notes Anna-Sofie Stensgaard. She’s a disease ecologist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

For instance, she and her colleagues looked at how climate change might affect three types of parasitic worms. These worms cause schistosomiasis (Shis-toh-so-MY-uh-sis). The disease affects more than 200 million people worldwide. Infected children grow weak and poorly nourished. They also may develop learning problems.

The team examined climate data and experimental evidence on how temperature affects the snails that host these parasites. And, she notes, “It is not just a matter of warmer equals more disease.” For instance, warming might bring some areas of Africa fewer cases of schistosomiasis. But that warming might also spread these infections to places that hadn’t seen the disease before. Those new sites will mainly be at the edge of current high-risk regions. Recent cases that popped up in southern Europe could be the first sign of this spread, Stensgaard suggests.

Her team’s study appeared in the February 2019 issue of Acta Tropica.

Many insects carry disease. That’s why “any change to climate is expected to have a big influence on the importance and distribution of insect-borne diseases,” says Jennifer Lord. She’s a biologist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in England. One of her recent studies looked at how that will likely play out for tsetse flies. These insects carry the parasites that cause sleeping sickness in people and nagana in cattle. Both diseases can be deadly.

Lord and other scientists built a computer model based on the fly’s biology. They also analyzed 27 years of climate data and tsetse-fly counts from Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe. This park is in a valley, so it’s warmer than higher-altitude areas nearby. The model predicted temperatures to climb over the next several decades. It also projected the park’s fly population would drop. The team expects that trend will continue.

But what could happen outside the park, at higher elevations, is worrisome. “Rising temperatures may have made some higher, cooler areas of Zimbabwe more suitable for tsetse,” Lord says. Many of those places don’t have the flies now. But they do have many more people and cattle than the valley does. So, she notes, “Any arrival of tsetse there may increase disease.”

A warmer climate also may drive disease-carrying mosquitos into new regions, including higher elevations that used to be too cool for them. Some of those migrating mosquitos are likely to spread malaria to those higher-altitude sites. That’s the conclusion of one 2014 study in Science.

Malaria parasites attack the liver and blood cells. People with mild cases suffer with fevers, headaches and chills. In worse cases, the blood can’t carry enough oxygen. Sometimes malaria also attacks the lungs and brain. Roughly 435,000 people died from the disease in 2017, notes the World Health Organization.

Mosquitoes can also carry dengue (DEN-gay) into new areas. This virus causes fevers and severe joint pain. Most new areas are likely to be next to or near to places where the mosquitoes live now. This shift would present risks to people on all continents except Antarctica, note Ebi at the University of Washington and a colleague. They published their 2016 study in Environmental Research.

Similar shifts may occur for other diseases as well. But there’s no one-size-fits-all forecast. That’s because different species will not all respond the same way to changes in their environment. In general, though, low-income countries will be hit the hardest. And within those places, women, children and the elderly are expected to fare worst.

Even in richer countries, children and older people are more apt to get certain diseases. Among the reasons why: Poor people often lack the means to eat well, to get good healthcare and to avoid living in high-risk regions.

Taking action

The more the average global temperature climbs, the worse climate’s health impacts will be. “Each additional unit of warming will increase the risks for adverse health outcomes,” says Ebi. Fortunately, she adds, “There’s a lot we can do now to reduce the number of people who are suffering and dying from climate change.”

Governments and health agencies can help people plan and adapt. Timon McPhearson is an ecologist at the New School in New York City. His work on resilience looks at how cities can adapt to climate change. “Every city is getting hotter — and getting hotter faster than the global average,” McPhearson says. Yet while cities are hot spots, some areas are hotter than others.

To explain that variation, he says, “all we need to do is look at [what sits on] the land and the building height.” One of his studies showed this with data for New York City. “What you get,” he says, “is if it’s paved, it’s hot.”

Such information can help planners bring help to those places that will need it most. For example, older and low-income people have less money for air conditioning. So cities might focus efforts on hot spots with higher concentrations of people in those groups, McPhearson suggests. Cities might also make those places a priority for planting more trees, which can bring cooling shade. And they can set up neighborhood programs to make sure people are safe or cool places to find refuge in when heat waves strike.

One way to slow climate change is to cut emissions of the pollutants responsible. And people can do that by using energy very efficiently or switching their sources of energy from fossil fuels to renewable fuels (such as wind). Too often, people focus only on the costs for those actions, Ebi says. In fact, she notes, “almost all the mitigation policies benefit our health — and they benefit our health now.”

Indeed, pollution already imposes huge costs to society. “We can save hundreds of millions of dollars in hospitals and people not dying early by mitigating [climate change] now,” Ebi says.

And while climate change is a global issue, cuts in emissions also provide local health benefits, Kinney notes. People there get cleaner air and cleaner water very quickly. “It’s a win-win if we take action,” he says. “It always turns out the health benefits far outweigh the costs.”