Did builders of Egypt’s first pyramid use a water-powered elevator?

Controlling the flow of water might have hoisted huge stone blocks, a new study suggests

Egyptian King Djoser’s pyramid, shown here, is nearly 4,700 years old. A new study suggests a water-powered elevator inside this structure helped lift the heavy blocks used to build it.

Anton Petrus/Moment/Getty Images

By Bruce Bower

Waterpower may have given a big lift to the builders of Egypt’s first pyramid.

It was built for King Djoser, the first ruler of Egypt’s Third Dynasty. That was nearly 4,700 years ago. The structure’s stone platforms get smaller as they rise from the ground. The six levels stand roughly 62 meters (200 feet) tall in the Saqqara necropolis. That’s a vast ancient burial ground in northern Egypt.

Researchers now suggest that ancient people used a water-powered system to construct this pyramid. How? Builders would have controlled flows of water into and out of a large shaft inside the pyramid. The water’s movement would have lifted and lowered a platform that carried building stones to higher levels.

Scientists shared this idea August 5 in PLOS ONE. The team was led by Xavier Landreau. He has a background in materials science and physics. He also founded a private research institute known as the Paleotechnic to study ancient technologies. It’s in Paris, France.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Puzzling pyramid building

There’s no broadly accepted explanation for how people built pyramids in ancient Egypt. It took millions of massive blocks. Some of those blocks weighed up to 2,500 kilograms (5,500 pounds).

Scholars have proposed several techniques — including ramps and cranes — to move such hefty stone blocks. Scientists have also thought about rope-and-pulley devices and rolling wooden rods attached to stones.

Other studies have hinted that water played some role in building pyramids.

Earlier this year, researchers reported a newfound Nile tributary. (A tributary is a freshwater stream that feeds into a larger river.) This stream borders a chain of 31 pyramids, including Djoser’s. It’s dried up now. But boats carrying workers and building blocks could have traveled this branch of the Nile between 3,700 and 4,700 years ago. They might have docked near to sites where the pyramids now stand.

But water likely played an even bigger part in building Egypt’s first pyramid, Landreau says. Designers of Djoser’s pyramid devised techniques for controlling water flow, he now argues. This field of knowledge is known as hydraulics.

A water-powered possibility

The proposed hydraulic system is based on a computer model. That model included data on features inside the pyramid and on a network of underground tunnels at the site. The team also added detailed satellite images of the region. These all helped to model ancient rainfall and runoff levels.

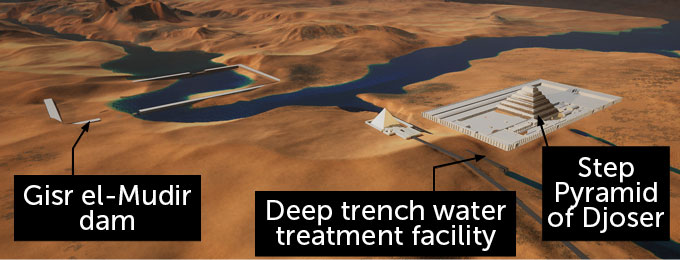

In addition to the pyramid itself, the model also included a walled enclosure several hundred meters (yards) away. Known as Gisr el-Mudir, this structure was first described in the 1700s. But its exact purpose has long been a puzzle.

In the new model, Gisr el-Mudir would have captured floodwater that flowed through desert channels during heavy rains. Structures in the walls of the enclosure fed the water to a basin just west of Djoser’s burial grounds. Periods of intense rain may have temporarily turned that basin into a lake. Such a lake would have then drained into a section of a limestone trench around the burial complex. That trench is now known as the Dry Moat.

Water from the Dry Moat could have entered two large shafts. One was a north shaft inside the pyramid. Granite chambers near the bottom of both shafts contained stone plugs. When removed, water could rush in.

Landreau’s group thinks the north shaft is the framework for a water-powered lift. They think a huge wooden float rested above its granite chamber. That float would have been attached to long ropes. These ropes could have passed over pulleys at the top of the shaft before looping around to attach to a lift platform.

Ancient engineers would have designed the float and lift platform to counterbalance each other as water filled or drained from the shaft.

Workers hauling building stones could have gotten onto the lift platform at ground level. Or they might have gotten on through a tunnel several meters above ground level.

As water filled the shaft through the granite chamber, the float would rise and the platform descend. Water would be shut off when the platform reached the loading area. After placing tons of stones on the platform, the shaft would be drained. Then, as the float descended, it pulled on the ropes. And that yanked the platform and its cargo up to new construction levels.

Does this idea really hold water?

Researchers not involved with the study find the water power idea intriguing. But they are not convinced that pyramid builders ever used it.

One skeptic is Oren Siegel. He’s an archaeologist at the University of Toronto in Canada. Gisr el-Mudir could not have held enough water from occasional rains to maintain this hydraulic system, he argues. Instead, Siegel thinks Gisr el-Mudir may have been an early experiment. It could have been used to test the building of stone enclosures like those that would later, on a larger scale, surround pharaohs’ burial sites.

Kamil Kuraszkiewicz has doubts about something else: the proposed lake. It’s not mentioned in any ancient Egyptian writings. He suspects it may never have existed. Kuraszkiewicz is an Egyptologist in Poland at the University of Warsaw.

Djoser’s pyramid stones also each weighed, on average, some 300 kilograms (660 pounds). That may sound heavy. But these blocks were much smaller and easier for workers to move than the ones used for later pyramids, says Kuraszkiewicz. Building the proposed water-powered system, he says, would have required “much more effort … than to move the stone blocks using just manpower.”