‘Weather bomb’ storms send tremors through Earth

High-tech equipment can now detect the weak waves and help probe the planet’s depths

Powerful storms called weather bombs can send tremors through the Earth. Scientists may soon use those events to study the deep layers of our planet.

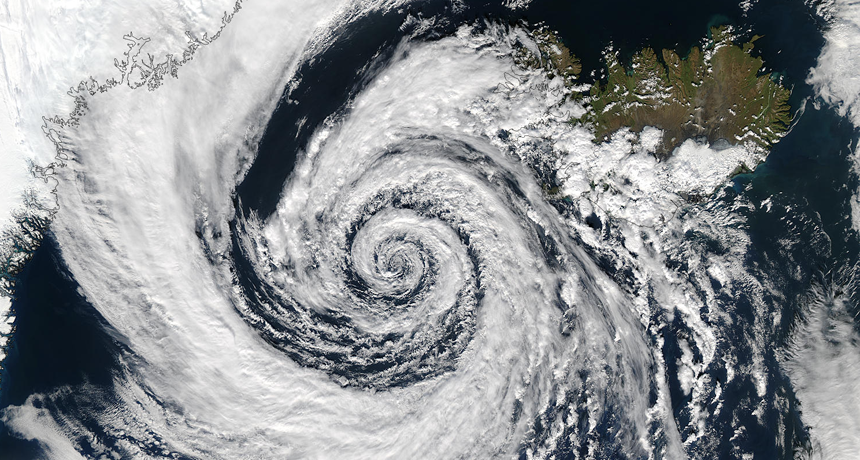

Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC

Recently, researchers detected a rare type of deep-Earth tremor. It was triggered by a hurricane. In this case, the source was a “weather bomb” strengthening rapidly over the North Atlantic Ocean.

“Weather bombs” are a type of extreme storm. Scientists can detect the seafloor quivers that these storms trigger. It starts as whipping winds stir up towering ocean swells. When two opposing ocean swells collide, the meet-up can send a pressure pulse down to the ocean floor. That pulse thumps the seafloor. The resulting Earth tremors — or seismic waves — penetrate deep into the planet.

Those seismic waves speed up, slow down or change direction as they move through the ground. Such motions depend on the type of material they pass through. In the past, scientists have carefully measured some of these movements caused by earthquake waves. That let them gather clues about the structure and composition of Earth’s deepest layers.

But some regions of Earth don’t see many earthquakes. One example is the middle of tectonic plates under the ocean. Luckily, weather bombs can generate their own seismic waves here.

Scientists previously had detected only one type of these storm-generated deep seismic waves. They are known as P waves. Such waves cause a material to compress and stretch in the same direction that the wave travels. Think of an accordion being stretched and compressed when someone plays it.

A second type of waves have proved more elusive. When storms form these S waves, they typically are weaker than P waves. They cause material to ripple perpendicular to the wave’s path. The effect is similar to when one end of a garden hose is jerked up and down. That action produces waves that travel along the hose’s length.

The new research tracked such S waves from a weather bomb. Details on the unusual waves appear in the August 26 in Science.

How they found them

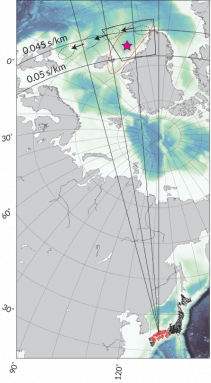

Kiwamu Nishida is a seismologist at the University of Tokyo in Japan. Ryota Takagi is also a seismologist. He works at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan. The pair hunted for the elusive S waves. To do this, they used a network of 202 seismic stations in Japan.

Typically, the S waves can be lost within Earth’s natural seismic background noise. But Nishida and Takagi combined and analyzed data from extra-sensitive seismometers. That let the researchers tease out the S-wave signals.

Those waves had been triggered by a cyclone — hurricane — in the North Atlantic, they found. That storm produced two types of S waves. SV waves shift material vertically (up and down) relative to Earth’s surface. They can form from P waves. SH waves shift material horizontally (left and right). Their origins are more of a mystery. Those SH waves may form from complex interactions between the ocean and the seafloor, Nishida says.

“We’re potentially getting a suite of new seismic source locations that can be used to investigate the interior of the Earth,” notes Peter Bromirski. He is an oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif. He wrote a commentary on the new research in the same issue of Science. Further study, he says, should help science “refine our understanding of how useful these particular waves will be.”

Keith Koper is a seismologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Combining measurements of P, SV and SH waves will “ultimately provide better maps of Earth’s mantle and maybe even the core,” he says. (The mantle is the layer between Earth’s outer crust and its core.) Koper and his colleagues made similar observations of S waves generated in the Pacific Ocean. Those waves were detected by a Chinese seismic network.

Koper’s group reported these related findings in the September 1 Earth and Planetary Sciences Letters. “It’s nice to see someone else get similar results,” Koper says. “It makes me feel more confident about what we observed.”