Welcome to the metaverse

If you play Fortnite or Minecraft, you’re already part of this growing virtual universe

The metaverse will change the world as people invent, learn, work, play and even solve real-world problems through virtual experiences.

NVIDIA Omniverse image

A teen with spiky white hair races his car past an enormous Tyrannosaurus rex. Later, he dances to some catchy music — while spinning and floating in midair. These scenes from the 2018 hit movie Ready Player One take place in a virtual world. The teen, Wade Watts, describes it as “a place where the limits of reality are your own imagination. You can do anything, go anywhere.”

A virtual place like this has a name — the metaverse. That name comes from Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science fiction book, Snow Crash. In these fictional stories, the metaverse transforms humanity and our world. It offers a tempting escape from a reality that has gone horribly wrong.

Meanwhile, in the very real here and now, engineers, businesspeople and even kids are building an actual metaverse. It’s not very much like the immersive, realistic virtual worlds of science fiction — at least not yet. The metaverse of 2022 includes some virtual reality, or VR, experiences. It also includes huge concerts in Fortnite and Roblox creators who make millions. You can find holograms of famous people, too, along with digital twins of cities and so much more.

The metaverse isn’t just one thing or one place. It’s a collection of “shared virtual worlds,” explains software engineer Liv Erickson. Here, people can connect and collaborate together. Just as the internet connects many different types of websites, images and videos, the metaverse is beginning to connect many different types of games, apps and experiences. Most of them will be 3-D and social.

Do you play Minecraft? Then you’re spending time in an early example of the metaverse. It’s part of the metaverse because people socialize there and also experiment and build in 3-D. Arinjay is an 8th grader who lives in India. “The thing I enjoy the most about Minecraft is the freedom you have,” he says. “Your creativity and imagination is your only limit!”

One day, says Jeff Kember, people will visit the metaverse for “everything from hanging out and being social, to working on collaborative projects, performing experiments and visiting new places, real or imagined.” Kember is a 3-D designer with experience in making video games and movies. Now he works on a software platform called Omniverse at the tech company NVIDIA. Its headquarters are in Santa Clara, Calif.

You bring the metaverse to life every time you create something in Minecraft. The same is true when you design a new online avatar or go on Fortnite to hang out with friends.

You become one of the people who decides what the metaverse will become and how we will later use it. Will the metaverse offer an escape from reality? Will it instead enhance reality with new layers? Will it track our every move and deluge us with advertising? Or will it encourage new ways to create and connect with others? Let’s dive in and find out.

Where is the metaverse?

Today, the metaverse is mostly on screens. Eventually, though, it will surround us.

VR headsets will transport us to completely virtual worlds. Augmented reality projectors will make hologram-like virtual objects and characters appear in the real, physical world.

Online, you can only read, listen or watch. In the metaverse, you’ll also move, touch, explore and experience. “We don’t just think with our minds,” says Toshi Anders Hoo. “We think with our entire bodies. And we think with our environment. And we also think socially.” Hoo is a media expert who directs the Emerging Media Lab at the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto, Calif.

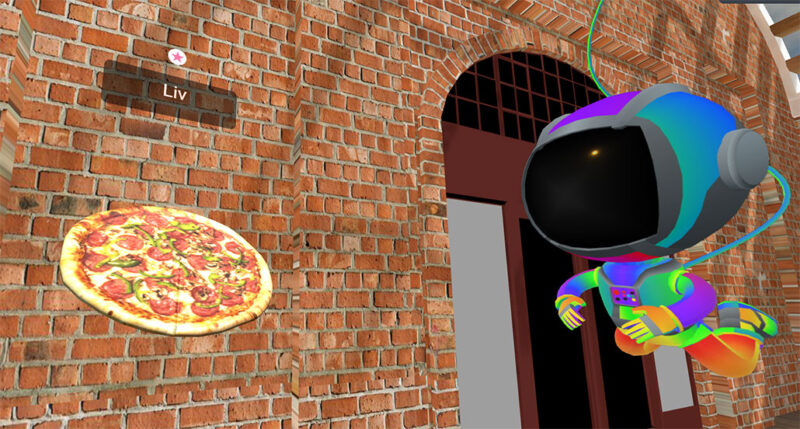

Erickson already works in the metaverse. For instance, they once showed up for a work meeting as a pizza. Not dressed in a pizza costume. Their meeting took place in a virtual world and their avatar was a pizza.

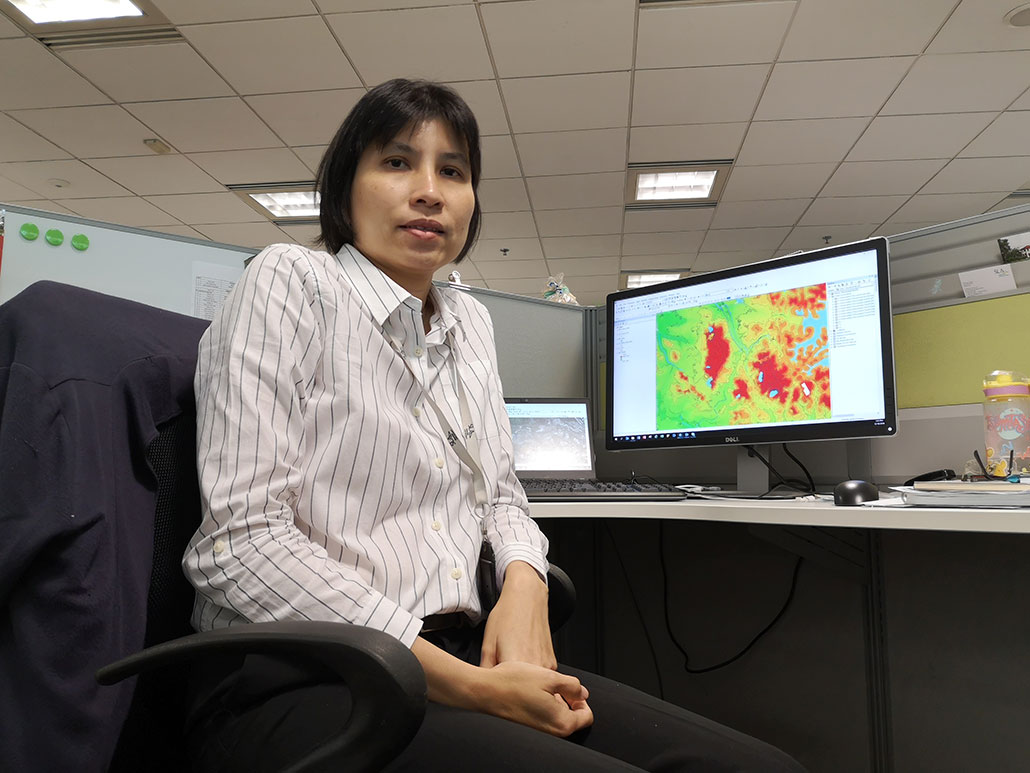

See that pizza? That’s Liv Erickson in Hubs, having a meeting. The other picture is Erickson in real life, with a VR headset. They change their avatar regularly. “For a while I was running around as a paper clip. It’s always funny,” they say, “when I forget what I’m wearing.”

A manager at Mozilla Hubs in New York City, Erickson and their team have been meeting in a virtual office since the COVID-19 pandemic began. However, for their entire career Erickson has been working to bring the metaverse to life. Currently, they work on Hubs. It is an app sort of like Zoom. One difference: everyone meets as avatars in a 3-D virtual space. Users can redesign this space and add anything they want to it. “It’s kind of like walking into a video game for your community or your work,” explains Erickson.

The evolving metaverse

If the internet is one parent of the metaverse, video games are the other. Some games — especially Roblox, Minecraft and Fortnite — have become more like destinations in the early metaverse. People go there not just to play but also to hang out with friends and have memorable experiences.

In April 2020, the raging pandemic meant it wasn’t safe to attend concerts in person. So hip-hop artist Travis Scott put on a free show inside the game Fortnite. More than 12 million people showed up as avatars and watched. The concert set a record for the most people ever participating in a game event at one time.

Technically, those millions weren’t all in one huge virtual space, though. Fortnite split them into groups of 100. Each group viewed its own stream of the same concert. Erickson explains, “Generally speaking, it’s hard to simulate a lot of humans in one spot — we move too much.” The most people they’ve ever seen in one virtual space was around 420. And “that was a very uncomfortable experience,” they say. (People often looked jittery or partially frozen. The software just couldn’t keep up with animating all those avatars at once.) The future metaverse will need a better way for many people to interact in virtual spaces at once.

Another reason to visit metaverse-like games is to tinker, design and build. Often, you can even sell what you’ve created. On the game platform Roblox, people can make their own games and items. They can also spend real money on games or accessories for their avatars.

Samuel Jordan, who also goes by the handle Builder_Boy, joined Roblox as a teen in 2011. Now, he’s a successful fashion designer. In 2021, he made $1 million selling virtual earrings, jackets and more.

Evo Heyning has spent time on Roblox and many similar platforms. But Heyning is not trying to become a millionaire. They’re making art and experiences. “You can build a roller coaster,” they say, and “test out ideas.” They also are meeting people. “I feel as connected to my virtual friends as I feel to my physical friends,” Heyning says.

Interactivation is a real musical instrument invented in a virtual world. Six people play it at once. They push buttons to control a Tesla coil, an electricity generator that makes noise as an electric current flows through it.

Heyning has been producing and creating interactive media since they started playing Second Life in 2005. This game offered an early glimpse into the metaverse. It mimics real life. Inside it, avatars set up homes, meet other avatars and buy virtual items. Heyning once worked with a team in Second Life to build an interactive musical instrument. In 2009, they built a real version of this same instrument — called “Interactivation” — and displayed it at a Maker Faire festival.

Now, Heyning helps run the Open Metaverse Interoperability Group. This group is working on building a metaverse that will not belong to any one company. That’s important because the technology that makes an immersive experience possible has to capture a huge amount of data about someone. If one company controls the metaverse, it would also control all of that information. It could use people’s data to advertise to or manipulate them. That’s a scary idea.

In a so-called “open” metaverse, people would keep control of their own data.

Space for everyone

Many people play video games because they love to dive into fantasy and become someone else. Some people even get addicted to gaming or to the internet. Certainly, some people could get addicted to the metaverse or use it to hide from reality. But being in the metaverse doesn’t mean you have to leave the real world behind. This digital environment can mesh with the real world in fascinating ways. People can test out ideas virtually and then bring those ideas to life — as Heyning did with their musical instrument.

Or people can take parts of the real world and make them virtual, available for anyone to experience. This is what Kai Frazier is doing.

Frazier used to teach middle-school history outside of Washington, D.C. “A lot of my students had never left our neighborhoods,” she says. She wanted to take her students to the museums in the city. Yet even though the museums were free, her school couldn’t afford the buses to get there. So, Frazier set out to solve this problem.

She wound up selling everything she owned and moving out to Oakland, Calif., to start the company Kai XR. It launched in 2020. Now it provides students with virtual field trips and a makerspace where they can design things in 3-D. On one of the field trips, students explore the official Obama portraits at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery. Another “trip” takes them around the lab where the groundbreaking CRISPR gene-editing technology was developed.

Frazier has no tech background. So sometimes she has felt out of place. Still, she says it’s important for her to show up and make her ideas a reality. “I was a homeless child,” she says. “It taught me to be really resourceful and really scrappy.”

Kids and teens experiencing homelessness or poverty may need extra help to take part in the metaverse. For example, they may only have access to a shared family smartphone. That’s why Frazier made sure her virtual field trips work on any device. She also has partnered with companies that are putting Kai XR onto tablets. These will be made available for free at some schools.

Virtual models of the real world make it possible to visit places and meet people that would normally be out of reach. Already, virtual versions of famous people have “performed” in movies, concerts and TV ads. A virtual Whitney Houston went on tour in 2021, for instance, even though the real Whitney Houston died in 2012.

In the metaverse, you can also become people of many different backgrounds and experience different cultures. You can literally walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. Liv Erickson loves how this flexibility of identity gives people power over how they want to show up online.

But it may not always be a good thing.

“I have this fear,” Erickson says, “that I’ll meet someone on an online platform and develop a friendship, only to realize it was a bot designed to be my friend and sell me products.”

Bots and scammers already exist online. Their tricks may become more harmful when they are avatars with bodies instead of names with profile pictures.

Creating metaverse ‘twins’

Virtual models can help people design a better real world in which to actually live. Digital twins are simulations of real things or places. This isn’t new technology. NASA created the world’s first digital twins of spacecraft in the 1960s. However, in the metaverse, digital twins become immersive. These 3-D virtual copies feel like the real thing. What’s more, multiple people can work with them at once.

Engineers are making digital twins of everything from cars and jet engines to entire factories. With a digital twin, people can test out ideas before making expensive changes in reality. They can also update the digital twin as new data come in from sensors in the environment or on the same device or building. That makes it possible to predict and fix problems before they risk becoming major failures.

Entire cities can have digital twins. Michael Jansen is a founder and chief executive of Cityzenith. This company makes computer programs that cities can use to create a digital twin. “Sometimes people call it Minecraft for architects,” Jansen says of this software. His company is working with several U.S. cities, including Los Angeles, Calif., Las Vegas, Nev., and Phoenix, Ariz. Each digital twin “looks like the real city,” says Jansen. City planners use the twin to virtually try out technologies that might improve how buildings in their cities function or use resources, such as energy.

Singapore, a city that is also a country in Southeast Asia, was one of the first to create a digital twin. That was back in 2014. To do this, the city first needed to create detailed 3-D maps. It is still carrying out regular 3-D mapping surveys to keep its virtual twin up-to-date. The more detailed and accurate these maps are, the more people can do with the digital twin.

A research institute at the National University of Singapore, for instance, did a study on which buildings could capture the most solar energy. This will help the city decide where to put solar panels. The National Parks Agency is using the twin to find the best spots to plant new trees. The digital twin will also help provide the detailed mapping info that will allow robots, drones, self-driving cars and other vehicles to navigate the city.

Digital twins aren’t perfect, of course. They may not accurately match reality. Also, bad guys could potentially hack a digital twin to plan an attack or disrupt important services. For these reasons, Singapore doesn’t make all of its digital-twin data publicly available.

The metaverse will likely contain some fun fantasy worlds and games such as the ones in the movie Ready Player One. But when fully realized, the metaverse will be so much more than that. It will mirror the real world and enhance our understanding of it.

The metaverse even has the potential to make the world a better place. Using digital city twins to combat climate change is only the beginning. If people spend more time meeting in virtual spaces, they could cut how much they need to travel for work. That could reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. If people spend more money on virtual goods, they may make less real trash.

The future isn’t something that happens to us — it’s something we all create. And all of our voices matter. “Everybody has a role in creating the metaverse,” says Frazier. If you feel there’s no place for you, then “make your own place,” she says. What type of metaverse do you want to create?

Kathryn Hulick has been a regular contributor to Science News for Explores since 2013. She’s covered everything from acne and video games to ghosts and robotics. This piece was inspired by her new book: Welcome to the Future: Robot Friends, Fusion Energy, Pet Dinosaurs, and More. (Quarto, November 2021, 128 pages).