What is the role of in-person classes in COVID-19’s spread?

New data haven’t shown that schools pose a big coronavirus risk to kids and their families

New studies suggest masks and other measures to prevent viral spread can keep schools from becoming COVID-19 super-spreader sites.

Drazen Zigic/iStock / Getty Images Plus

As most kids go back to school, how will in-person learning affect the spread of the coronavirus? Some people worry that kids who have not gotten a vaccine could catch COVID-19 from their classmates. Afterward, infected kids might spread it to vulnerable adults. The good news: New data suggest that schools need not pose a super-spreader threat. This appeared especially true when people wore masks in school and classrooms were well ventilated.

Susi Kriemler is a pediatrician who focuses on how diseases spread. She works at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. Schools aren’t the culprit, she says: “I’m a believer that most infections that affect children come from parents.” And Kriemler is part of a team that has some data to back that up.

Her group took blood samples from nearly 3,000 children at 55 schools. Samples were collected in three rounds: June to July 2020, October to November 2020 and March to April 2021. The researchers looked for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. It’s the virus that causes COVID-19. Having antibodies would indicate the kids had been infected at some point.

The team then looked for clusters of COVID-19 cases within classrooms that might point to student-to-student spread. No evidence for such a spread emerged, they reported July 19 at medRxiv.org. Instead, any infections in schools appeared to reflect the rates of COVID-19 seen in the general community outside the school.

Other scientists have not yet reviewed this new report. But its findings echo those from a study of four schools in Orange County, Calif.

One of the four schools had 97 percent of its students learning from home. Its kids also had the highest infection rate among these schools. Kids at that school also lived in neighborhoods with the highest transmission rate. That suggests kids got infected in their community, not at school. Pediatrician Dan M. Cooper of the University of California, Irvine and his team shared their findings July 24 in Pediatric Research.

Another of the four schools the team studied had 93 percent in-person classes. Its kids had high rates of mask-wearing. COVID-19 rates in that school were half of what was seen in the community around the first school. But the largely in-person school also had the lowest infection rate among the four schools that Cooper’s team studied.

It’s important to note that there also were some potentially other important differences in the four studied schools.

The mostly in-person school spent about $1,400 per student upgrading its facilities and putting anti-COVID measures in place. That’s more than many schools can afford. And all of those data for this study were collected before the new and super-infectious delta variant emerged.

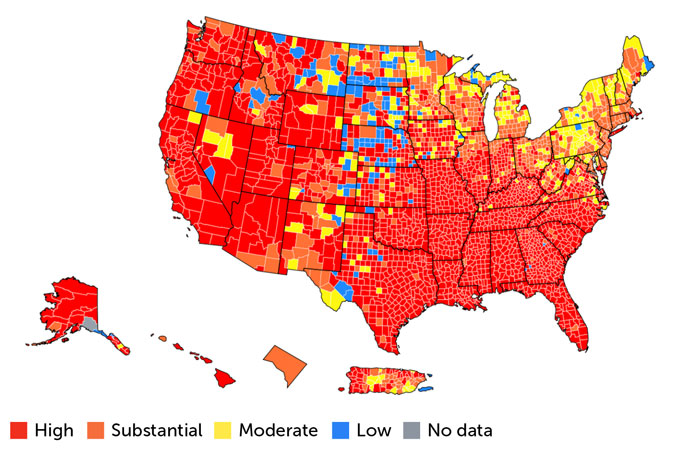

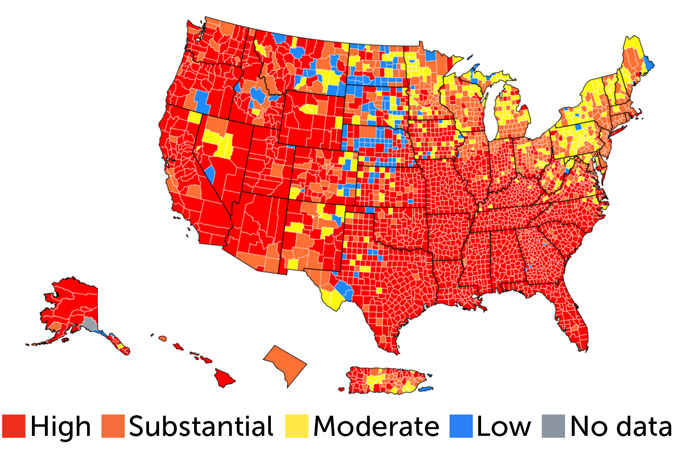

On maps made by the CDC, much of the country is now tinted red. This depicts areas where COVID-19 transmission rates over the last week are high — at least 100 or more people out of every 100,000. Most of the rest of the country is orange. These are areas where weekly infection rates are 50 to 99 people out of every 100,000 people. Those high infection rates have spilled over into kids at summer camps. Some campers brought the virus home. Later, it spread into their communities.

Hot spots

Back-to-school time is happening just as most of the United States has high or substantial numbers of new COVID-19 cases. This snapshot reflects the situation as of August 3. Red counties are where there are more than 100 cases for every 100,000 people in the last seven days; orange counties have 50 to 99 cases for every 100,000 people in that seven-day period. Under such conditions, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that everyone wear masks when indoors in public places, especially in schools.

SARS-CoV-2 transmission rates in the United States

Camp horror stories won’t necessarily be repeated in schools, though. Air cleaning, greater ventilation and wearing masks may cut down on the spread of even the delta variant. Still, it is not clear how widely schools will adopt such measures. The CDC recommends that everyone — kids, teachers, administrators, staff, visitors — wear masks when in schools. And this is true even for people who have gotten a vaccine.

Some places are starting school with mask mandates. Other states have banned schools from requiring such protective gear. Elsewhere, a mix of policies leaves it up to parents to decide whether their kids wear masks at school or get vaccinated (when it’s available to them).

Still, if everything is done correctly, schools don’t have to be COVID-19 hotbeds. Researchers who studied the four California schools suspect that “schools can be among the healthiest places for children to be so long as the right [protection] strategies are in place.”