What part of us knows right from wrong?

Scientists are learning how and why our brains evolved a conscience

Your conscience is what helps you decide whether your actions or impulses are good or bad, right or wrong.

JamesBrey/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

If you’ve seen the movie Pinocchio, you probably remember Jiminy Cricket. This well-dressed insect acted as Pinocchio’s conscience (CON-shinss). Pinocchio needed that voice in his ear because he didn’t know right from wrong. Most real people, in contrast, have a conscience. Not only do they have a general sense of right and wrong, but they also understand how their actions affect others.

Conscience is sometimes described as that voice inside your head. It’s not literally a voice, though. When a person’s conscience is telling them to do — or not do — something, they experience it through emotions.

Sometimes those emotions are positive. Empathy, gratitude, fairness, compassion and pride are all examples of emotions that encourage us to do things for other people. Other times, we need to not do something. The emotions that stop us include guilt, shame, embarrassment and a fear of being judged poorly by others.

Scientists are trying to understand where conscience comes from. Why do people have a conscience? How does it develop as we grow up? And where in the brain do the feelings that make up our conscience arise? Understanding conscience can help us understand what it means to be human.

Humans help

Often, when someone’s conscience gets their attention, it’s because that person knows they should have helped someone else but didn’t. Or they see another person not helping out when they should.

Humans are a cooperative species. That means we work together to get things done. We’re hardly the only ones to do this, however. The other great ape species (chimpanzees, gorillas, bonobos and orangutans) also live in cooperating groups. So do some birds, who work together to raise young or to gather food for their social group. But humans work together in ways no other species does.

Our conscience is part of what lets us do so. In fact, Charles Darwin, the 19th-century scientist famous for studying evolution, thought conscience is what makes humans, well, human.

When did we become so helpful? Anthropologists — scientists who study how humans developed — think it started when our ancestors had to work together to hunt big game.

If people didn’t work together, they didn’t get enough food. But when they banded together, they could hunt large animals and get enough to feed their group for weeks. Cooperation meant survival. Anyone who didn’t help out didn’t deserve an equal share of food. That meant people had to keep track of who helped — and who didn’t. And they had to have a system of rewarding people who pitched in.

This suggests that a basic part of being human is helping others and keeping track of who’s helped you. And research supports this idea.

Katharina Hamann is an evolutionary anthropologist, someone who studies how humans and our close relatives evolved. She and her team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany worked with both children and chimpanzees.

She led one 2011 study that put both children (two- or three-year olds) and chimps in situations where they had to work with a partner of their own species to get some treat. For the kids, this meant pulling on ropes at either end of a long board. For chimpanzees, it was a similar but slightly more complicated setup.

When the children started pulling the ropes, two pieces of their reward (marbles) sat at each end of the board. But as they pulled, one marble rolled from one end to the other. So one child got three marbles and the other got just one. When both kids had to work together, the children who got the extra marbles returned them to their partners three out of four times. But when they pulled a rope on their own (no cooperation needed) and got three marbles, these kids shared with the other child only one time in every four.

Chimpanzees instead worked for a food treat. And during the tests, they never actively shared this reward with their partners, even when both apes had to work together to get the treat.

So even very young children recognize cooperation and reward it by sharing equally, Hamann says. That ability, she adds, probably comes from our ancient need to cooperate to survive.

Children develop what we call conscience in two ways, she concludes. They learn basic social rules and expectations from adults. And they practice applying those rules with their peers. “In their joint play, they create their own rules,” she says. They also “experience that such rules are a good way to prevent harm and achieve fairness.” These kinds of interactions, Hamann suspects, may help children develop a conscience.

Attack of a guilty conscience

It feels good to do good things. Sharing and helping often trigger good feelings. We experience compassion for others, pride in a job well done and a sense of fairness.

But unhelpful behavior — or not being able to fix a problem we’ve caused — makes most people feel guilt, embarrassment or even fear for their reputation. And these feelings develop early, as in preschoolers.

Robert Hepach works at the University of Leipzig in Germany. But he used to be at the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology. Back then, he worked with Amrisha Vaish at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in Charlottesville. In one 2017 study, the two studied children’s eyes to gauge how bad they felt about some situation.

They focused on a child’s pupils. These are the black circles at the center of the eyes. Pupils dilate, or get wider, in low light. They also can dilate in other situations. One of these is when people feel concerned for others or want to help them. So scientists can measure changes in pupil diameter as one cue to when someone’s emotional state has changed. In their case, Hepach and Vaish used pupil dilation to study whether young children felt bad (and possibly guilty) after thinking they had caused an accident.

They had two- and three-year olds build a track so that a train could travel to an adult in the room. Then the adults asked the kids to deliver a cup of water to them using that train. Each child put a cup filled with colored water on a train car. Then the kid sat in front of a computer screen that showed the train tracks. An eye tracker hidden below the monitor measured the child’s pupils.

In half of the trials, a child hit a button to start the train. In the other half, a second adult hit the button. In each case, the train tipped over, spilling the water before it reached its destination. This accident seemed to be caused by whomever had started the train.

In some trials, the child was allowed to get paper towels to clean up the mess. In others, an adult grabbed the towels first. A child’s pupils were then measured a second time, at the end of each trial.

Kids who had a chance to clean up the mess had smaller pupils at the end than did children who didn’t get to help. This was true whether or not the child had “caused” an accident. But when an adult cleaned up the mess that a child had thought he had caused, the child still had dilated pupils afterward. This suggests these kids may have felt guilty about making the mess, the researchers say. If an adult cleaned it up, the child had no chance to right that wrong. This left them feeling bad.

Explains Hepach, “We want to be the one who provides the help. We remain frustrated if someone else repairs the harm we (accidentally) caused.” One sign of this guilt or frustration can be pupil dilation.

“From a very young age, children have a basic sense of guilt,” adds Vaish. “They know when they have hurt someone,” she says. “They also know that it’s important for them to make things right again.”

Guilt is an important emotion, she notes. And it starts playing a role early in life. As kids get older, their sense of guilt may become more complex, she says. They start to feel guilty about things they haven’t done but should. Or they might feel guilty when they just think about doing something bad.

The biology of right and wrong

What happens inside someone when she feels pangs of conscience? Scientists have done dozens of studies to figure this out. Many of them focus on morality, the code of conduct that we learn — the one which helps us judge right from wrong.

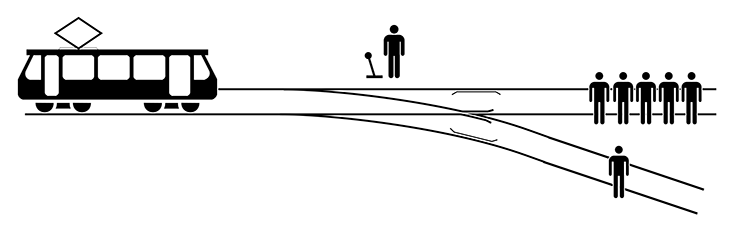

Scientists have focused on finding the brain areas involved with moral thinking. To do this, they scanned the brains of people while those people were looking at scenes showing different situations. For instance, one might show someone hurting another. Or a viewer might have to decide whether to save five (fictional) people by letting someone else die.

Early on, scientists expected to find a “moral area” in the brain. But there turned out not to be one. In fact, there are several areas throughout the brain that turn on during these experiments. By working together, these brain areas probably become our conscience. Scientists refer to these areas as the “moral network.”

This network is actually made up of three smaller networks, says Fiery Cushman of Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. This psychologist specializes in morality. One brain network helps us understand other people. Another allows us to care about them. The last helps us make decisions based on our understanding and caring, Cushman explains.

The first of these three networks is made up of a group of brain areas that together are called the default mode network. It helps us get inside the heads of other people, so we can better understand who they are and what motivates them. This network involves parts of the brain that become active when we daydream. Most daydreams involve other people, Cushman says. Although we can only see a person’s actions, we can imagine what they’re thinking, or why they did what they did.

The second network is a group of brain areas often called the pain matrix. In most people, a certain part of this network turns on when someone feels pain. A neighboring region lights up when someone sees another in pain.

Empathy (EM-pah-thee) is the ability to share someone else’s feelings. The more empathetic someone is, the more those first two brain networks overlap. In very empathetic people, they may almost completely overlap. That shows that the pain matrix is important for empathy, Cushman says. It lets us care about other people by tying what they are feeling to what we ourselves experience.

Understanding and caring are important. But having a conscience means that people must then act on their feelings, he notes. That’s where the third network comes in. This one is a decision-making network. And it’s where people weigh the costs and benefits of taking action.

When people find themselves in moral situations, all three networks go to work. “We shouldn’t be looking for the moral part of the brain,” Cushman says. Rather, we have a network of areas that originally evolved to do other things. Over evolutionary time, they began to work together to create a feeling of conscience.

Just as there’s no single moral brain center, there’s no such thing as a single type of moral person. “There are different paths to morality,” Cushman says. For example, some people are very empathetic. That drives them to cooperate with others. Some people instead act on their conscience because that’s what seems the most logical thing for them to do. And still others simply happen to be in the right place at the right time to make a difference to someone else, Cushman says.

The feelings behind conscience help people maintain their social ties, says Vaish. These emotions are critical for making our interactions with others smoother and more cooperative. So even though that guilty conscience may not feel good, it appears important to being human.