What you need to know about ‘murder hornets’

Here’s what’s been overlooked about the arrival of alien hornets in North America

An invasion of the world’s largest hornet species in North America could spell trouble for the honeybees it kills as food for its young.

USDA

By Susan Milius

At least three new specimens of the so-called “murder hornet” have turned up in the Pacific Northwest in 2020. They’re Asian giant hornets, a species (Vespa mandarinia) that recently invaded North America. This beast is a threat to honeybees. It’s sting is also something few humans would ever forget.

Biologists tried last year to stamp out the invaders. But the May and June discoveries now suggest invaders made it through the winter. The two in Washington State were queens. One had already mated, according to the state’s agriculture department.

One of these big, orange-and-black insects was found dead in a roadway near Custer, Wash. Sven Spichiger is an insect specialist with Washington’s Department of Agriculture. He announced on May 29 that the body was that of an Asian giant hornet. It had probably hatched last year, he says. This queen was likely out to found a new colony. The second queen turned up wiggling on somebody’s porch near Bellingham, Wash. The person stomped on it and reported it June 6.

Earlier, scientists in Canada confirmed their first giant hornet of 2020. A sharp-eyed person reported it May 15 in Langley, British Columbia.

This wasp earned its nickname from preying on honeybees. It can swoop down and grab them out of the air. The hornet then carries this treat home to nourish young hornets. A raiding party of several dozen Asian giant hornets can kill a whole hive. The attackers can kill thousands of bees in just a few hours. In such mass attacks, hornets bite the heads off adult bees. Attackers leave the adult bodies in heaps. They carry off young bees as protein for young hornets.

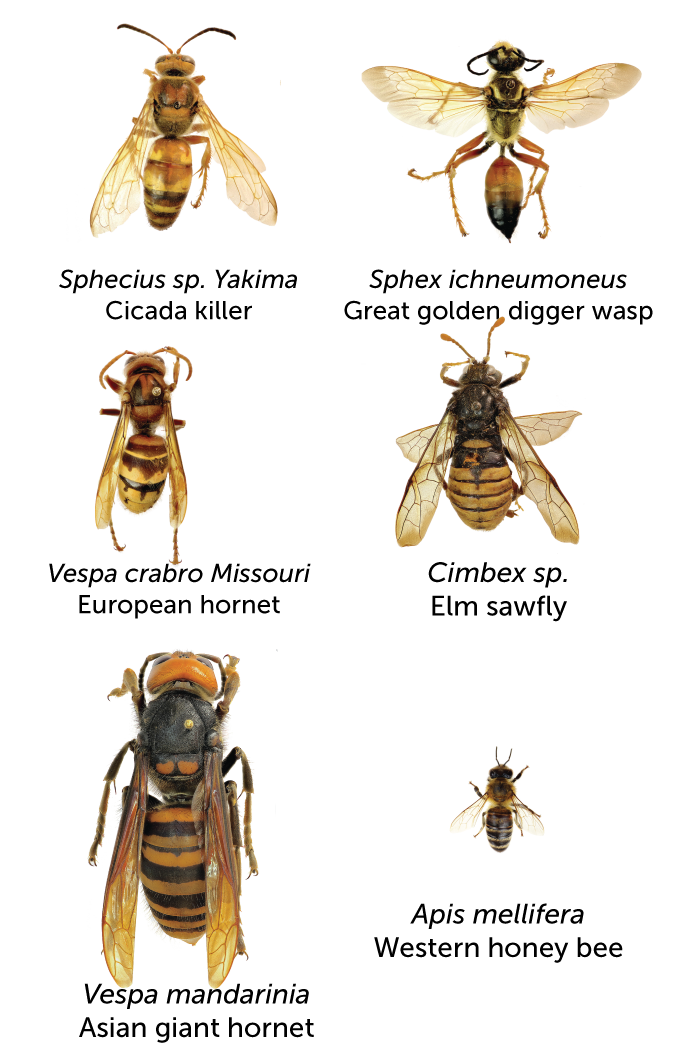

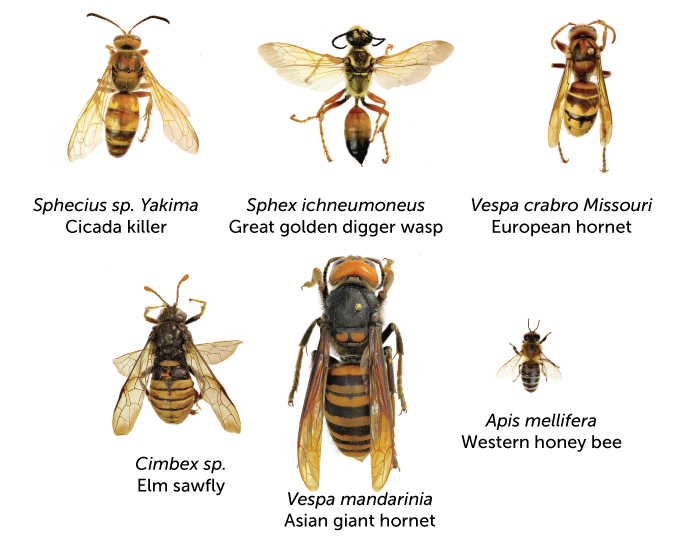

V. mandarinia ranks as the world’s largest hornet. Queens can grow some 5 centimeters (2 inches) long, about the length of an average-sized woman’s thumb. Wingspans can exceed 7 centimeters (2.8 inches), not quite the full width of a woman’s palm. Workers are smaller.

Such true hornets are big, predatory, colony-forming wasps. They belong to the genus Vespa. None are native to North or South America. Most are native to Asia. They need meat to feed their young. That’s in contrast to honeybees, which collect plant pollen as protein. Another difference: A honeybee dies after its single-use stinger rips out of its body. Hornets can sting over and over.

The latest hornet-identification report lists 22 species. They may be striped or blotched. Their color patterns range from browns and rusts to gold and bluish-blacks. North America also has several native wasps popularly nicknamed hornets. These insects, however, belong on a nearby — but different — twig of the insect evolutionary tree.

Amid dire news accounts about the Asian giant hornets, a few facts have been overlooked. For one, North America had at least one earlier close call with this species. It was not publicized at the time. That early episode also had a happy ending, at least for the people and native insects of North America.

Here’s what we know so far — and don’t — about Asian giant hornets and the threats they pose.

How ‘new’ is this invasion?

In September 2019, beekeepers in Canada tracked down and destroyed a hornet nest in the ground. It was near a public footpath in Nanaimo, near Vancouver. Lone flying hornets also showed up on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border. One appeared at a hummingbird feeder near Blaine, Wash.

But that wasn’t the Asian giant hornet’s first touchdown on North American soil.

California had an overlooked close call in 2016. And it wasn’t just some lone hornet hiding in a cargo container, notes Allan Smith-Pardo. He’s an entomologist in Sacramento, Calif. He works for the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (It’s part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.) He was the scientist charged nationwide with identifying suspicious wasps or bees found in cargo or mail. An inspector flagged an express package coming into the San Francisco airport.

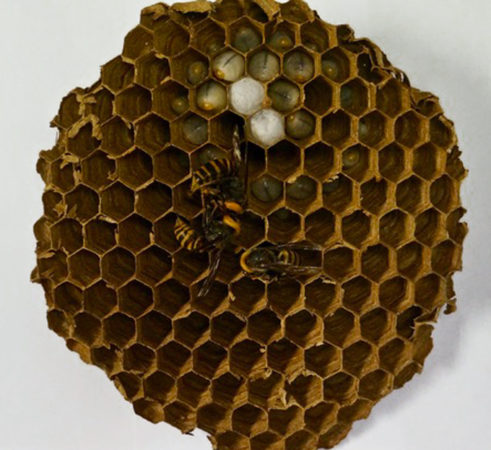

It held some papery honeycomb-like nest. The inspector wondered if someone was smuggling in bees. U.S. rules strictly ban that. (The goal is to keep out diseases and pests that could hurt U.S. bees.) Smith-Pardo identified the package as something dramatic. It was a whole nest of Asian giant hornets! “There were no adults in the package,” he says, “but plenty of pupae and larvae.” A few were still alive.

Why would somebody send a nest of hornets? In their native home, “collected adults, pupae and larvae are soaked in liquor,” notes retired entomologist Jung-Tai Chao. Some people believe this “hornet liquor” will ease the pain of arthritis, he explains. While at the University of Georgia in Athens, he studied the social behaviors of paper wasps. He also has studied hornet ecology at the Taiwan Forestry Research Institute.

The 2016 hornet package was opened in a secure room, so no insects escaped. In the end, that potential insect disaster became no more than a brief notice on page 23 of the May 2020 issue of Insect Systematics and Diversity. But that report looked only at hornets intercepted on U.S. borders during one decade. That means there might have been earlier run-ins with giants.

Is the Asian giant hornet the first hornet to try invading North America?

Far from it.

V. crabro is another hefty hornet. It spread into New York from Europe or Asia back in the mid-19th century. Now it can be found in scattered places east of the Rockies. These hornets nest in hollow trees and cozy nooks within walls. People who blunder too close can get painful stings, says Bob Jacobson. He’s a retired entomologist in Cincinnati, Ohio, with an interest in hornets and venoms. His cousin was also stung by the species.

Like the Asian giant hornet, V. crabro attacks honeybees. Jacobson has seen it go after bumblebees, too. It may even target yellow jackets and other wasps. Unlike the new invader, however, members of V. crabro hunt alone. Each picks off a bee on a flower or at a hive. It doesn’t gang up for mass slaughter of whole colonies.

Other hornets also have turned up in North America without stirring public interest. Between 2010 and 2018, inspectors stopped four species besides the giant at U.S. borders. In Canada, just last year, entomologists identified two different invasive hornet species. These included V. soror, which is almost as big as the Asian giant. Whether any of these other species will make a permanent home in North America is not known.

Why attack honeybees?

The Asian giant hornet doesn’t actually specialize in honeybees, notes James Carpenter. He’s a hornet specialist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. In temperate climates, workers of this species forage alone, often for beetles.

But a nesting colony only lasts one year. Toward fall, when the colony’s time is running out, its workers face heavy demands for protein to raise what will be the next year’s queens. Workers now band together to raid. Several dozen may attack high-value targets. This could include whole nests of honeybees, other types of hornets and yellow jackets.

The giant hornets “slaughter the adults, then carry back the brood as food for their larvae,” Carpenter explains. “Besides the impact on honeybees, then, they might have an impact on native yellow jackets.”

How bad is the sting?

The Asian giant hornet delivers a big dose of a fairly strong venom. Justin Schmidt and his colleagues calculated this based on research with mice. Schmidt works in Tucson at the Southwestern Biological Institute and University of Arizona.

A giant hornet’s sting can deliver a lot of venom — some 1,100 micrograms (dry weight). That’s more than seven times as much as some dainty little honeybee delivers. The hornet venom also has a pretty strong knockdown power. Based on what venom did to lab animals, researchers say that just one full sting would have a 50 percent chance of killing a decent-sized rodent.

Schmidt has spent decades recording how painful he finds various stings. He has personal data on more than 90 insects, but the Asian giant hornet isn’t one of them. At least not yet. But from talking to colleagues who have been stung, he estimates that the Asian giant hornet’s sting is equivalent to three to 10 yellow jackets stinging at once. That’s painful. But it’s “not the end of the world,” he adds. Bullet ant stings, he finds, are roughly 10 times more painful.

A much-quoted number from a 2007 paper puts Japan’s death toll for people stung by V. mandarinia at 30 to 50 people per year. That includes people with allergies to insect venom. Less-quoted parts of this report from Japan point out that of the 15 people hospitalized for stings and discussed in the paper, those with fewer than 50 stings had a good chance of surviving.

If this hornet gets established, will people need to stay indoors to survive the invasion?

Paul van Westendorp doesn’t think so. He’s the main bee-keeping specialist for British Columbia.

Asian giant hornets are at the apex, or top, of major insect predators. “Apex predators are maybe very fierce in what they can do, but there are only a few of them around,” he says. Consider orcas (killer whales), another apex predator. “On a beautiful, hot summer day,” van Westendorp says, “one will normally have no hesitation to go for a nice swim in the ocean — even if we recognize that there are orcas out there.”