When Darwin got sick of feathers

The man who started evolutionary biology had some bad moments over a bird

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Susan Milius

|

|

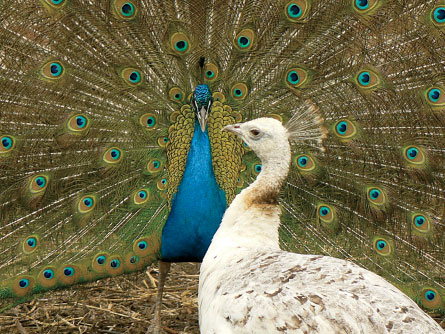

A peacock’s tail looks gorgeous to us, and probably to the less-decorated female (in front). Yet the tail doesn’t look as if it helps a male survive, which worried Darwin for a while.

|

| Joen 12/iStockphoto |

The great biologist Charles Darwin wrote to another scientist in 1860 that looking at a peacock feather made him sick.

OK, he was halfway joking (you can tell from the rest of the letter). But still, you might wonder what was wrong with the man.

He lived more than 100 years ago, but he was talking about the same kind of peacocks we know today. Peacocks, the name for males of the species, fan out tail feathers in blues and greens that are bright as jewels. Not obviously something to throw up about.

Darwin’s problem was that peacocks and some other upsetting life forms might have ruined the major work of his scientific life. Or would have if he hadn’t worked out a tough puzzle.

For years, he studied pigeons, barnacles, beetles, orchids and many more kinds of creatures. He put together the ideas we know today as evolution, a theory of how all living things today are related. They came to have their current forms as they changed over many millions of years.

Bumper stickers hadn’t been invented in Darwin’s day (to be fair, neither had cars). Otherwise he might have ridden around England with “SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST” between his taillights.

That notion of survival of the fittest was a huge part of his ideas of how evolution worked. In any kind of animal, plant or whatever, there’s variety among individuals, he pointed out. Some mice run faster than other mice. Some hawks have better eyesight. Some raspberry bushes make more berries. And some men might be slightly pudgy — but talented enough to come up with great scientific ideas. Not to mention any names, of course.

Those individuals best suited to survive in their particular home range will have more offspring than those that are less well suited. The best-suited survivors can pass along the speed or eyesight or other trait that made them especially successful at surviving. Over generations, those useful traits would become more common for that kind of creature than the less useful traits. Darwin called this process natural selection.

Now for the sickening part about peacocks. Those fancy tails making the bird more fit to survive — he thought that just didn’t make sense!

A peacock tail can stand five feet high. All those huge feathers make flying harder, not easier. Even sprinting along the ground becomes difficult.

Peacocks don’t need all those feathers for finding food. The peahens, the name for females of the species, do just fine with small tails. Females have plainer colors too, so it’s hard to see how huge, jewel-colored tails could be so important for survival in the species’s males.

Other kinds of creatures raised the same upsetting problem. Darwin wrote about big, heavy horns on male beetles or on male deer, called stags. (Dung beetles don’t need horns to spend their lives collecting poop. It’s not going to fight back.)

Darwin figured it out though. These fancy bird feathers and animal horns often do not give a creature direct help in surviving. What they do is help with finding a mate.

So Darwin wrote about a second force in evolution, which he called sexual selection. It works much like natural selection. A bird with the most beautiful tail ends up as the father of lots of children, and he can pass along his beauty. Over generations this kind of bird’s tail gets fancier. Or, for another example, male dung beetles use their horns to fight each other, and the winner gets the girl. Over generations that kind of beetle’s horn gets more effective.

Still, Darwin called this a separate kind of selection from the survival-of-the-fittest type. For one thing, the two forces can pull in opposite directions. (People aren’t the only species to do dumb, possibly life-threatening things when showing off to impress individuals of the opposite sex.)

Sexual selection has been a powerful idea and scientists keep adding new twists to it. What’s more, evolutionary biologists today can look at a peacock’s tail without losing their lunch.