When physicians and veterinarians team up, all species benefit

Partnerships can help tackle diseases that affect animals and people

Dromedary camels can carry the MERS coronavirus, which can infect humans. Here, veterinarians take a sample of fluid from the animal’s windpipe. They are trying to better understand how the virus is transmitted from camels to humans.

Courtesy of U. Wernery

By Liz Devitt

A chimpanzee named Pandora changed the way physician Barbarita Natterson Horowitz thought about practicing medicine. Veterinarians at the Los Angeles Zoo, in California, were worried Pandora had a heart problem. The zoo did not have the medical tools it needed to study the chimpanzee’s heart. But a human hospital would. So the zoo doctors called Horowitz, a cardiologist and professor of medicine. She works at the University of California, Los Angeles, not far from the zoo. She takes care of people with heart problems.

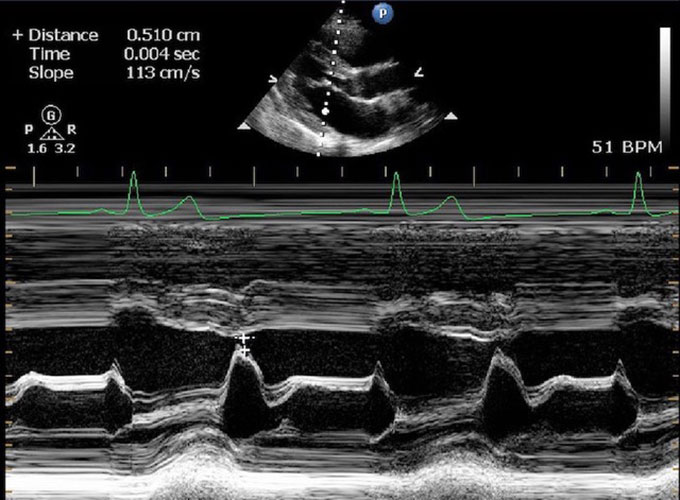

One way Horowitz checks people’s hearts is with a special type of ultrasound. First, a patient must be under anesthesia. Then Horowitz slips a small probe down their throat toward the stomach. Once level with the heart, the probe bounces sound waves off the heart to create images. To her trained eyes, those images show details such as the thickness of the muscle, blood flow and how hard the heart is pumping. Zoo vets are highly trained in animal health, but none at the Los Angeles Zoo knew how to do this type of heart exam.

Later on, Horowitz was asked to ultrasound a gorilla’s heart. Soon she was looking at the hearts of lions, tamarins and other animals. The more animals she saw, the more she talked with veterinarians.

“I heard about animals with diabetes, breast cancer, obesity … the list went on and on,” she says. She had not grown up with pets in her home. “It opened my eyes to how many diseases I was taking care of in human beings that also happened in animals.”

Now, Horowitz works with wildlife experts and doctors from many medical fields. One of her studies is comparing the hearts of human marathon runners with those of racehorses. Another study looks at how giraffe hearts develop compared to those in people. She also co-wrote a book, Zoobiquity, about health problems that animals and people share. “Sometimes it’s a little overwhelming,” she says. “Everywhere I look, I see so many connections.”

Learning about disease in other species can help doctors take better care of animals and people. This cross-species approach to animal and human health is called “one medicine” or “one health.”

The approach is not new. Some of the greatest discoveries in medicine have come from studying diseases in both people and animals. For example, a virus that infected cows and people led to the vaccine for smallpox, the only human disease ever completely wiped out.

Physicians and veterinarians who share their expertise can improve medicine and health in all species.

Going great ape

Ilana Kutinsky is a cardiologist who treats people at a hospital in Michigan. She always wanted to be a veterinarian. But allergies to dogs and cats scrapped that plan. Instead, she followed in her father’s footsteps and became a doctor of osteopath. “It’s like being a regular medical doctor, just with a more holistic approach,” she explains. That includes aspects of overall wellness such as diet and lifestyle.

Then, like Horowitz, she did more training to become a cardiologist. Kutinsky studied images of patient hearts and measured parts of each one to see if it was healthy. How big was the heart? How fast did it beat? How thick was the muscle of the left ventricle, the chamber that squeezes blood to the rest of the body? She compared each patient’s measurements to those from healthy hearts.

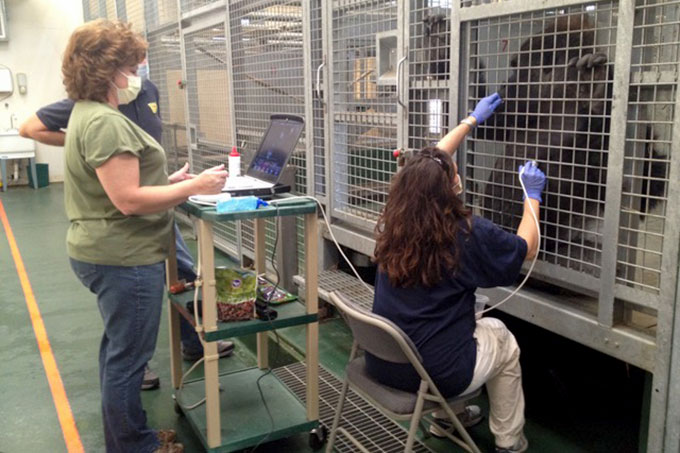

“I was sitting in a dark room day after day, reading ultrasound images of human patients,” she recalls. So when veterinarians from the Denver Zoo in Colorado called to ask if she would do ultrasounds of their great apes, she had a ready answer: “Absolutely!”

Gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees and bonobos — the great apes — often die of heart disease. But no one really knew why.

The first ape heart that Kutinsky imaged belonged to a gorilla named Kondu. Once she had the image, she asked the vets what the normal measurements were for gorilla hearts. No one knew. There were not enough data on gorilla hearts. But there were many more requests for heart ultrasounds of great apes.

As she imaged more and more, “I started to get a feel for the difference between human and gorilla hearts,” says Kutinsky.

But she wanted to learn more. Forty-one percent of gorillas housed in zoos have heart disease, or die from heart disease. “I didn’t feel it was okay to do nothing,” Kutinsky says. She called Hayley Murphy, a veterinarian and the deputy director of Zoo Atlanta, in Georgia. Murphy had worked with great apes since her first zoo post at Zoo New England in Boston, Mass.

Together, Kutinsky and Murphy decided to build a database to learn what was normal — or not — for gorilla hearts. Their teamwork led to looking at other great apes. This became the Great Ape Heart Project (GAHP), which is based at Zoo Atlanta.

Veterinarian Hayley Murphy draws blood from the leg of an anesthetized gorilla during an exam.Courtesy of H. Murphy/Zoo Atlanta

A team of gorilla experts and caretakers record body measurements and other health information during an exam. Courtesy of H. Murphy/Zoo Atlanta

Veterinarian Hayley Murphy uses ultrasound to image a gorilla’s heart for the Great Ape Heart Project’s database. Courtesy of H. Murphy/Zoo Atlanta

With training — and treats — a gorilla named Kidogo allows the GAHP team at Zoo Atlanta to put an ultrasound probe on his chest to examine his heart.Courtesy of Marietta Dindo Danforth/Zoo Atlanta

This is an echocardiogram image of an ape’s heart. The wedge shape at the top is a cross-section through the heart. The white lines show heart muscle and the black is where blood flows. A heart specialist can measure the thickness of the walls and how well the heart contracts.Courtesy of H. Murphy/Zoo Atlanta

Ten years later, their database now has more than 1,000 heart ultrasounds. Some are from healthy great apes and others from ones with heart disease. Teams of human cardiologists, veterinary cardiologists, zoo veterinarians, animal care specialists and scientists send images from all over the world.

While GAHP has helped these specialists to study ape health, the data collected also help in managing the health of great apes. “We could never lose sight of the fact that endangered great apes were dying from heart disease as we were researching it,” says Murphy.

Next, Kutinsky wants to study how genes are linked to heart disease in some families of great apes. And Murphy plans to dig into the database to figure out what causes heart disease in apes. Many of the animals have scarred heart muscle, even young apes, she finds. Scarred muscle loses its stretchiness, much like an old elastic band. Now it can’t pump blood as well as a healthy heart. In people, scarred muscle often is caused by high blood pressure. But there’s not much data on blood pressure in great apes. Not yet.

And, notes Murphy, “Even though human hearts are different from the great apes, maybe we will learn things that can help people.”

The canine connection

A greyhound named Pretty helped a veterinarian and a physician find new ways to treat cancer in both dogs and people.

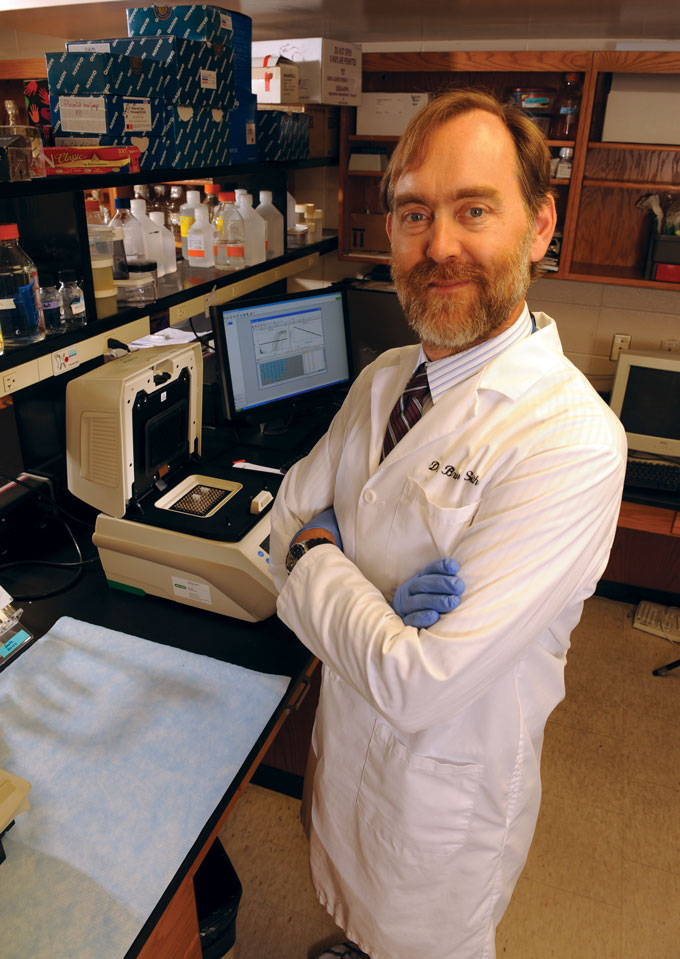

David Curiel is a doctor who uses viruses to kill tumors. A cancer biologist, he works at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Most of us think of viruses as something that makes us sick. When viruses infect cells, they make many copies of themselves. Then they kill the infected cell so those copies can spread. Curiel puts that viral talent to work. He leads a research team that builds viruses that copy themselves in cancer cells but not in healthy ones. The idea is that the viruses will kill the cancer cells as they copy themselves and spread.

One day, Curiel was puzzled when one of his tumor-killing viruses would not copy itself in the way he expected. He called Bruce Smith, a veterinarian and researcher at Auburn University in Alabama. He knew that Smith sometimes used viruses as delivery boxes to carry genes into cells. He hoped Smith might have an idea about how to work with this finicky virus.

When they talked, Smith mentioned that similar viruses can infect dogs and people. He also noted that dogs get many of the same cancers that people do, including bone cancer and breast cancer. This was news to Curiel, who had always focused on human health.

Hoping to ultimately help people, Curiel designed a virus that would infect bone-cancer cells in dogs. Bone cancer is common in dogs, but it is very hard to treat. The cancer tends to spread quickly to the lungs. Children can get the same cancer — and in them it’s just as hard to treat. Smith started a small clinical trial to see if the custom-made virus could help his canine cancer patients.

The dogs are not a testing lab for his ideas, Smith stresses. “We are asking what tools we have to help each other,” he says of his teamwork with Curiel.

Pretty was one of the dogs in the study. She already had been treated with cancer-fighting drugs. Her front leg had been amputated to stop the cancer from spreading. Still, her chances for living a long life were not good. So she received injections of the tumor-killing virus.

A year later, Smith saw shadows on Pretty’s chest x-rays that likely meant the cancer was back. Surgeons took out those spots. But surprisingly the spots were not cancer. Studied under a microscope, they turned out to be what doctors call caseous necrosis (Kas-ee-us Neh-KROW-sus), says Smith. “Or, as I like to tell everyone who is not in the medical field, cheesy dead stuff.”

That cheesy stuff meant the dog’s own immune system was primed to fight the tumor — even though the virus was long gone, says Smith. That got both doctors thinking: How can we make that happen all the time?

That type of thinking has led both doctors to search for better ways to target tumor cells with their viruses. Several medical teams are now working on viral therapies for bone cancers. Curiel has also tested viruses to treat cancer in people.

“In trying to answer a scientific question, we ended up with a new therapy for cancer in humans and a new therapy for cancer in dogs,” says Curiel. His many years of work with Smith also led him to seek out other veterinarians to work with.

And these days, technology is creating tools that never existed when Smith was in school. With 3-D printing, someday we’ll be able to custom-build a virus that matches what each individual patient needs, he says.

Calling on camels

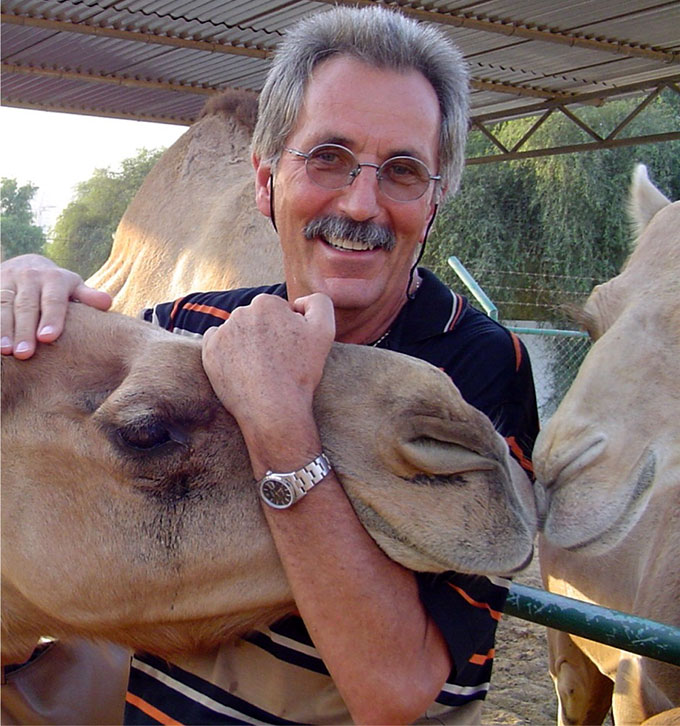

A phone call is not the only way vets and physicians team up. For veterinarian Ulrich Wernery, it started with camels.

“I love camels more than anything in the world,” says Wernery, who earned his veterinary degree in Berlin, Germany. He fell in love with the animals when his work took him to Somalia, a country in eastern Africa in which many of the world’s camels live. Years later, he saw a job for a camel expert in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). He took it. He’s now the scientific director of the Central Veterinary Research Laboratory in Dubai in the UAE. “I was not a camel expert when I started the job,” he says. “But I am now.”

In 2012, that expertise became important to human health. Dozens of people in the Middle East started dying from a mysterious illness. Laboratories in the Netherlands and Spain identified a new virus causing the illness. They called it the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus, or MERS CoV. (This virus is a relative of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.) Often infections with these viruses jump from animals to people. Teams of experts hunted for the virus in various animals, such as bats. But some of the sick people had been around camels. Dromedary (one-humped) camels became a suspected source of the virus.

Wernery was immediately intrigued. “Why do these camels harbor this coronavirus? And why does it suddenly appear in people now?” Wernery asks. He was hundreds of kilometers away from the main MERS outbreak in Saudi Arabia. But he did have a lot of camels.

Curious, he tested 50 camel blood samples saved from his early days at the laboratory. He was shocked to find the samples all contained antibodies to the “new” virus. That meant the camels had the MERS virus long before people got sick from it.

“It is not a disease for camels,” he notes. “The camels do not get sick from the virus. But they carry it and can give it to people.”

But not all camels spread the virus. Only camel calves around four to eight months old could give the virus to people, he found. These calves have a gap in their immunity. Older animals have time to build up immunity to the virus. Baby camels are protected by virus-killing antibodies in their mother’s milk. But calves slowly lose that protection. Until they have time to build their own immunity, they can spread the virus in their snot.

Getting young camels to make antibodies to the virus would protect people. But camel owners don’t want to vaccinate their animals against a virus that only makes people sick. Camelpox is a virus that camel owners do worry about. Working with other scientists, Wernery produced a two-way vaccine against both MERS and camelpox.

He is now testing the vaccine on 30 camels. If all goes well, the camels will make antibodies to both viruses. And, hopefully, the young camels will not shed MERS virus in their noses. Wernery often shares his research results with human physicians. Most recently he talked with doctors in South Korea. That country has no camels, but still suffered a MERS outbreak in 2015. More than 186 people were infected with the virus and 38 died.

“We have to be alert to prevent the spillover of diseases from animals to humans,” says Wernery. “We as veterinarians should be prepared to see this, to explain this and to prevent it.”

All on call

In the future, veterinarians and physicians may work together right from the start of their medical training. In 2012, a small community started a program with students at the University of California, Davis. It is now called the Knights Landing One Health Center.

The clinic started out with medical students helping local residents. But then the community asked if veterinary students could join the program, too. Once a month, both pets and people can get free preventive health care.

“The buildings are separate, but the students share ‘joint rounds,’” explains Paulina Crook. She is an advisor to the veterinary students at UC Davis. At rounds, students talk about topics that affect the health of people and animals. They might talk about specific cases. One client was seen for flea bites, then took their dog to the veterinary clinic for flea treatment. “This all becomes so much more related than the students imagined,” says Crook.

“It’s all tied together. Animals, people, the environment,” says Horowitz. “Everything is about recognizing the value of connection.”