Atlantic: One of the world’s five oceans, it is second in size only to the Pacific. It separates Europe and Africa to the east from North and South America to the west.

biologist: A scientist involved in the study of living things.

biology: The study of living things. The scientists who study them are known as biologists.

coauthor: One of a group (two or more people) who together had prepared a written work, such as a book, report or research paper. Not all coauthors may have contributed equally.

copepod: A type of small crustacean found in salt and fresh water. Some species of them are plankton, floating with the currents. Others spend time on the sea floor. These animals aren’t limited to oceans; copepods also are found in freshwater, from ponds to puddles. They often serve as food for larger species, and most eat phytoplankton — single-celled organisms that get their energy from the sun.

crustaceans: Hard-shelled water-dwelling animals including lobsters, crabs and shrimp.

diet: The foods and liquids ingested by an animal to provide the nutrition it needs to grow and maintain health. (verb) To adopt a specific food-intake plan for the purpose of controlling body weight.

ecologist: A scientist who works in a branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings.

environment: The sum of all of the things that exist around some organism or the process and the condition those things create. Environment may refer to the weather and ecosystem in which some animal lives, or, perhaps, the temperature and humidity (or even the placement of things in the vicinity of an item of interest).

fjord: A long, narrow inlet with steep sides, created in a valley carved by glacial activity.

invasive species: (also known as aliens) A species that is found living, and often thriving, in an ecosystem other than the one in which it evolved. Some invasive species were deliberately introduced to an environment, such as a prized flower, tree or shrub. Some entered an environment unintentionally, such as a fungus whose spores traveled between continents on the winds. Still others may have escaped from a controlled environment, such as an aquarium or laboratory, and begun growing in the wild. What all of these so-called invasives have in common is that their populations are becoming established in a new environment, often in the absence of natural factors that would control their spread. Invasive species can be plants, animals or disease-causing pathogens. Many have the potential to cause harm to wildlife, people or to a region’s economy.

isotope: Different forms of an element that vary somewhat in mass (and potentially in lifetime). All have the same number of protons in their nucleus, but different numbers of neutrons.

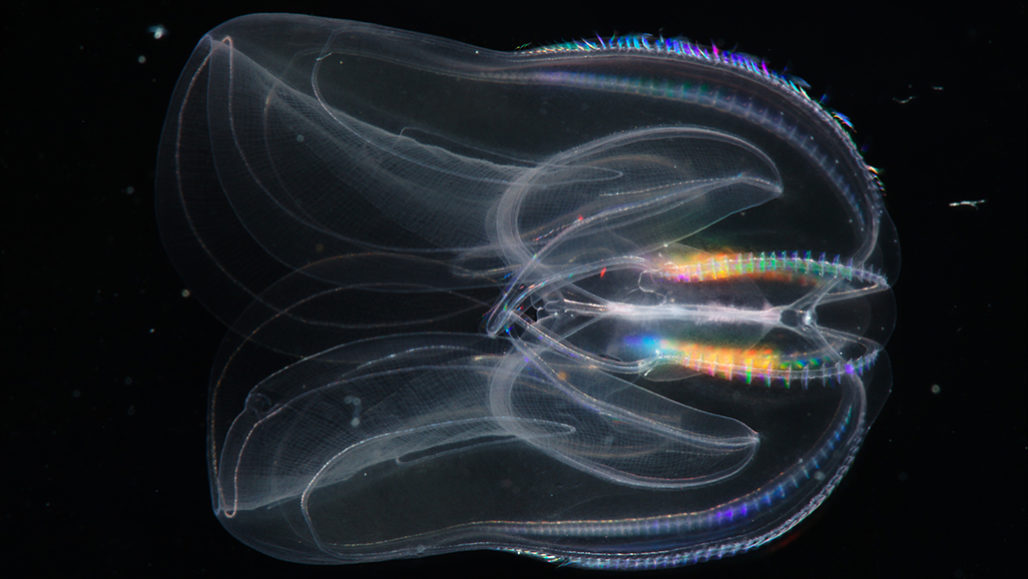

jellies: (in biology) These are gelatinous animals that drift in water (mostly seawater) or brackish (semi-salty) estuaries. For more than 500 million years, they have moved around the oceans by pumping pulses of water through their jelly-like tissue. Their body often has an umbrella-shaped bell. Trailing from around a central mouth may be many tentacles. Although jellies don’t have brains, they do have a nervous system which can sometimes detect light, movement or certain chemicals. Some members of this family, known as cnidarians, are known as jellyfish. In fact, none are true fish but related to hydras and corals.

larvae: Immature insects that have a distinctly different form (body shape) than when they are adults. For instance, caterpillars are larval butterflies and maggots are larval flies. (Sometimes this term also is used to describe such a stage in the development of fish, frogs and other animals.)

marine: Having to do with the ocean world or environment.

native: Associated with a particular location; native plants and animals have been found in a particular location since recorded history began. These species also tend to have developed within a region, occurring there naturally (not because they were planted or moved there by people). Most are particularly well adapted to their environment.

nitrogen: A colorless, odorless and nonreactive gaseous element that forms about 78 percent of Earth's atmosphere. Its scientific symbol is N. Nitrogen is released in the form of nitrogen oxides as fossil fuels burn. It comes in two stable forms. Both have 14 protons in the nucleus. But one has 14 neutrons in that nucleus; the other has 15. For that difference, they are known, respectively, as nitrogen-14 and nitrogen-15 (or 14N and 15N).

population: (in biology) A group of individuals from the same species that lives in the same area.

prey: (n.) Animal species eaten by others. (v.) To attack and eat another species.

sea: An ocean (or region that is part of an ocean). Unlike lakes and streams, seawater — or ocean water — is salty.

species: A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.