Why animals often ‘stand in’ for people

Researchers study lab mice and other species in the hunt to understand the human body — and what will keep it healthy

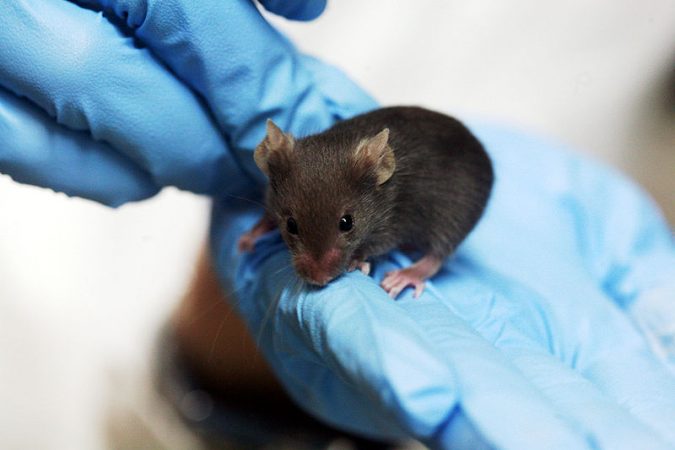

The brown Norway rat, here, is widely used in biomedical experiments, including tests on diabetes, aging and cancer. Scientists publish the results of roughly 100,000 experiments a year that had used rats or mice to “model” effects in people.

Bill Branson, NIH

You might not think we have much in common with scampering mice or flitting fish. However, beneath their fur or scales, these creatures can bear a striking resemblance to people. Under a microscope, their cells and molecules are so similar to ours that many researchers use these and other animals to understand how the human body works — and to predict our likely responses to possible drugs or poisons.

When mice, fish and other animals are used in medical research, they are called models. Just as a model car resembles a real car, animal models are enough like people that researchers can use them in experiments. For a variety of reasons, researchers often cannot perform such tests on people.

Animal models can help researchers address a slew of questions. Will this cancer drug be safe for Grandma? Can anything prevent the mysterious heart failures that cause sudden death in thousands of young athletes each year? Might that soap ingredient harm us — or fish and insects — after it washes down the drain? Will that flea-killing spray hurt Fido — or the baby who crawls on a treated rug?

Triclosan is found in many household products. These products range from toothpastes, shampoos and hand washes to fabrics, kitchen sponges and toys.

Before the research by Pessah’s team, other studies had raised questions about whether this widely used chemical might harm people. However, researchers cannot measure a chemical’s hazards by exposing healthy volunteers to varying doses and then counting how many sicken or die. That would not be ethical, safe or even legal. Those are major reasons scientists turn to animal models.

But there are other reasons, too. By tweaking an animal’s DNA or using other means to inflict changes in their cells and tissues, some organisms can closely model human diseases. This way, researchers can check how well a potential therapy works — or how it might prove harmful — before moving on to test it in people. Animals also can help scientists screen large numbers of chemicals quickly to identify a few that might be beneficial. Many drugs you’d find on a pharmacy shelf were first tested on animals.

Animal models aren’t perfect

Though useful and essential for some kinds of research, animal testing has its limits. “Even if you do high-quality work, there’s still the problem of jumping from one species to another,” says Michael Bracken. He’s an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven, Conn. Sometimes chemicals and cells act differently within an animal than they do in people.

This harsh reality occasionally rears its head in clinical trials. These are studies involving people. Such tests come at the final stage of developing a new drug. Here, researchers randomly assign volunteers into groups. Some will receive an experimental drug. Others might get either another existing treatment or a placebo (Pluh-SEE-boh). A placebo is an inactive material. Think of it as a dummy pill that looks just like the experimental drug. Treatments must pass these rigorous tests before regulators will let doctors use a new drug to treat patients.

And with good reason.

Consider a 1993 trial of a drug to treat hepatitis B. This viral infection attacks the liver. Each year, hepatitis B kills three-quarters of a million people. In the 1993 tests of an experimental drug, 15 hepatitis patients were treated with the drug. Seven — roughly half — soon died when a severe toxic reaction caused their livers to fail.

The researchers were shocked. The compound had caused no apparent problems in tests on mice, rats, dogs and monkeys.

Later, scientists discovered what went wrong. The tested compound looks and acts like the chemical building blocks of DNA, called nucleosides. Humans produce a special protein that delivers nucleosides across cell membranes. However, this delivery protein does not exist in mice, rats or other animals used in prior studies with the compound. As fate would have it, the compound disables that human transporter protein. This keeps new DNA from forming.

The damage occurred in cells throughout the body, with the liver taking the biggest hit. But this problem would never show up in non-human animals. So the original researchers had no clue the drug could poison people.

Gary Peltz works at the Stanford School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif. To prevent similar tragedies with other nucleoside mimics that might be headed for testing in people, Peltz and his colleagues created mice with “human” livers.

Peltz started with a strain of mice that lacks an immune system. That prevents their bodies from attacking — also known as rejecting — tissues from another animal. Then his team used a drug (not the test compound) to kill each mouse’s liver before transplanting human liver cells into their bodies. In time, those human cells would create a new, functioning liver.

Another set of mice got to keep their original — and healthy — livers. Those animals served as the experiment’s control mice. These were the animals against which the new mice with “human” livers would be compared.

After a month on the test compound, the control animals with mouse livers seemed to do fine. However, mice with the “human” livers quickly sickened. “After three days,” Peltz recalls, “the vets called me and said, ‘Your mice are extremely sick. What do you want to do with them?’”

Initially, Peltz’s team tested a very high dose of the drug — much higher than the doses used in the fateful 1993 human trial. So he cut the dose given to the group of animals. But these mice also developed liver damage. Had these mouse models been around two decades ago, they could have highlighted the risk this hepatitis drug posed. And that, Peltz suspects, could have prevented the tragic deaths in that 1993 trial. Peltz and colleagues described their findings in an April 15 study inPLOS Medicine.

Finding drug candidates

Animal models also can help at earlier steps in the creation of new medicines. For instance, scientists need to figure out which chemicals to test. But animal testing is costly and difficult. So researchers want to use only those compounds that might be able to “fix” the diseased cells or molecules that aren’t working correctly. They may have to sift through thousands of molecules for the few candidates that show promise.

Here’s how Jeffrey Saffitz took on the challenge. A cardiac pathologist, he works at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Mass.

Saffitz wanted to find potential drugs to keep the heart’s rhythm from going awry. Such an arrhythmia (Ah-RITH-mee-ah), or altered heart rate, can cause sudden death. In some cases, parents can unknowingly pass down the condition to their children. “It’s not unusual for the disease to go undiscovered in a family until a young, relatively healthy person drops dead,” Saffitz tells Science News for Students.

Mutations are unexpected changes to genes. They may occur by accident. Other times, a disease or pollutant causes them. Scientists had identified mutated genes that could cause the arrhythmia that Saffitz studies.

Based on this knowledge, Saffitz and his colleagues engineered a new strain of zebrafish. A strain is a group of individual organisms belonging to a species that share one or more distinctive characteristics. “The fish are really sick,” says Saffitz. “They have this really big, abnormal heart — and they die.” These zebrafish also contain the same mutation that shows up in people with a rare, severe form of arrhythmia.

The researchers further tweaked the animals’ genetic programming by inserting a firefly gene. This type of manipulation is an example of genetic engineering. The firefly gene contains the directions for a cell to make a protein. That protein emits light when the fish’s heartbeat begins faltering. In this animal model, any chemical given to the fish that dimmed or shut off the “light” might represent a potential drug for treating the arrhythmia.

Speedy and thrifty

You might wonder why the researchers didn’t screen the compounds using mice instead of fish. After all, mice are more similar to people. In a nutshell, it came down to time and cost. Just 24 hours after a fish egg is fertilized, “you have a beating heart,” Saffitz explains. “Within 48 hours, we could already see the heart is sick.” Mice, in contrast, take much longer — three weeks — to be born. Plus, they’re far more expensive to feed, house and rear.

With its zebrafish model, Saffitz’s team tested 5,000 compounds in about six months. Of those, just three looked promising. One had previously entered human testing. Decades ago, that compound went through a trial for bipolar disorder. This brain condition causes shifts in mood and energy levels that make it hard to carry out everyday tasks. The compound “got far enough to be tried in people,” says Saffitz. However, “we haven’t been able to access the data,” he explains. “So we don’t know whether [the drug] turned out to be safe or not.”

Meanwhile, the researchers did the next best thing. They tested the compound in other species. “Just because [the molecule] works in fish doesn’t mean it will work in mammals or people,” Saffitz says. Consider the difference in heart structure. A mammal’s heart has four chambers. Fish hearts have just two. Such structural differences might hint at other differences that could affect heart function.

So, to test the chemical in mammals, the researchers created two models of a different kind. Instead of using whole animals, these models used cells taken from live animals and grown in Petri dishes. In one case, the experts engineered cells from a rat’s heart to contain the same mutation as their zebrafish had. The second model instead used cells from a human heart. But they didn’t come directly from the heart. Scientists first took blood from two people with a severe, inherited form of arrhythmia. They then treated those cells, converting them into stem cells. Stems cells can be induced to mature into any other type of cell. Here, the researchers coaxed them into becoming heart-muscle cells.

In both rat and human cells modeling those in the heart, the test chemical seemed helpful. It kept the heart cells from dying. It also corrected specific protein abnormalities found in people with arrhythmia. The researchers reported their results June 11 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

A long road

As for the arrhythmia compound, “We don’t know exactly what it is doing,” Saffitz says. “We don’t understand the mechanism.”

Currently, his lab is trying to work out how the molecule restores the inner workings of cells to restore normal heartbeat patterns. If things go well, the group might team up with a drug company. Together, they might make tiny changes to the drug’s recipe, boosting its power. They’d also like to test the drug in larger animals and to find which dose of it that might be both safe and effective.

“Those are the steps you go through to take a molecule into humans,” Saffitz explains.

Luckily, people aren’t the only “guinea pigs” on whom potential medicines or toxic compounds are tested. Sometimes researchers use mice, rats and other organisms (and occasionally real guinea pigs). With the help of genetic engineering, some of these animals can model human diseases for the early phases of drug testing. And though they aren’t perfect replicas, animal models can save countless research hours and dollars by identifying which molecules, among many thousands, are actually worth testing in people.

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)