Why can’t bugs be grub?

Researchers are studying why some people think eating insects is gross — and how to change that

Billions of people around the world regularly eat bugs. Why do so many Westerners find the idea disgusting?

MauMyHaT/istockphoto

One Friday morning in May, 11-year-old Sarah Nihan went to school and did something she had never done before. She pulled a dry-roasted cricket out of a bowl and carefully lifted it to her mouth. “At first I was a little iffy,” Sarah admits. “I made the mistake of looking it in the eyes.”

At the time, Sarah was a fifth grader at Ellis School in Fremont, N.H. Before her language-arts class held its bug buffet, the students had learned all about the benefits of eating insects. Packed with protein and vitamins, insects are quite nutritious. And raising them takes far less land and water than raising traditional livestock, such as cattle. So as a food source, insects are better for the planet.

The kids wrote essays on the environmental and health benefits of eating bugs, or entomophagy (En-tuh-MAH-fuh-jee). They read a book about a student who ate a stink bug as defense against a bully. They watched videos of Asian people relishing tarantula burgers. Yet Sarah still had to brace herself and count to three before popping that bacon-and-cheese-flavored cricket into her mouth. “I told myself that I’m not going to lose to a bug,” she says. But after chewing a few seconds, she cringed.

She’s not alone. To most North Americans and Europeans, the thought of eating insects triggers the same reaction: Ewwww.

This isn’t how people react to all foods they dislike. For example, people who dislike asparagus usually don’t say it’s disgusting. “They just say it tastes bad,” points out Paul Rozin. “But they’d say goat intestine is disgusting.” We seem to save our revulsion for certain animal products.

Rozin is a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He’s spent decades studying how some foods have become taboo. He and other researchers are trying to learn where this disgust comes from — and whether it can be unlearned.

Eating your first bug isn’t always easy, as participants in the Bug Buffet learned.

Curriculum with a Cause/Facebook

Geography matters

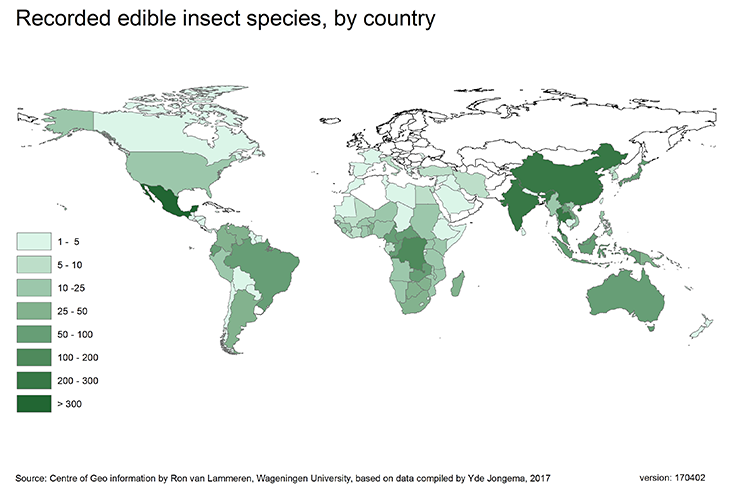

Insects aren’t gross to everyone. Indeed, some two billion people around the world savor them on a regular basis.

Most Westerners — people who live in North America and Western Europe — don’t eat insects. But the Western diet includes a number of foods that can seem just as gross when you stop to think about them. Cheeses are made with mold and bacteria. Escargot, a dish eaten in France and other countries, consists of cooked snails. Shrimp and lobsters look kind of like giant bugs. (In fact, they’re arthropods, the same group of animals that includes insects and spiders.)

So why do Westerners shun ants, grasshoppers and other creepy-crawlies? That question piqued the interest of Julie Lesnik. She’s an anthropologist at Wayne State University in Detroit, Mich. There, she studies how the human diet has evolved.

Lesnik has always been a picky eater. She never intended to study edible insects, let alone eat them. But while doing research in South Africa, she found evidence that primate ancestors of early humans used bone tools to dig into termite mounds. That suggested ancient humans ate insects. So when and why did Westerners quit eating bugs?

Some researchers think hunting for insects became less popular as ancient people found easier food sources in farming. If the land could support crops and cattle, why go after tiny scattered bugs with fewer calories?

Others explain the puzzle by looking at climate. Tropical countries get plenty of sun. That produces thicker vegetation, bigger insects and more kinds of them. People have better odds of finding an insect they like when they have lots to choose from year-round, Lesnik says. But farther north, where the seasons change, insects aren’t available during winter months.

Both ideas make sense. The earliest Europeans lived 18,000 to 22,000 years ago. That was during a period called the Last Glacial Maximum. Ice covered much of North America and northern Europe. To survive, people had to hunt deer and other large game. There wouldn’t have been many big, juicy bugs around. Could it be that insect-eating habits depend on where people live?

To test her idea, Lesnik gathered data on various factors that might affect whether cultures eat insects.

One such factor was agriculture. It’s likely that ancient hunter-gatherers chowed on insects. But people who raise animals and grow crops probably came to view insects as pests. That could make bugs less appealing.

Yet when Lesnik looked at a current map of insect-eating countries, she saw that agriculture was common in many of them. She also gathered data on the share of land in each country that’s good for farming. If agriculture were a key factor in insect eating, she’d expect people in farmable regions to eat fewer bugs. But that wasn’t the case.

She considered other explanations. For example, maybe the people who eat insects live in countries that are poor. Or maybe they don’t have enough farmed food to go around. If those theories were right, Lesnik would expect more insect eaters to be found in countries with crowded conditions or in low-income nations. Experts describe that last group as having a low gross domestic product, or GDP. (GDP is a way to measure the health and wealth of a nation’s economy.) However, Lesnik found no link between insect-eating and either GDP or population density. So insects aren’t just a fallback food for desperate people. Lesnik published her analysis last year in the American Journal of Human Biology.

As it turns out, “Where you are in the world is the number one predictor of who’s going to be eating insects,” Lesnik says. Latitude is how far north or south you are from the equator. And in eight out of every 10 people, latitude alone predicts the likelihood that they’ll eat insects. Warmer parts of the world, Lesnik says, just have more bug-eating.

On the practical side, geography explains why early Westerners didn’t eat insects. But it doesn’t explain the emotional part — the disgust. And that disgust has not only persisted in Western culture but also crossed borders.

Yuck factor

Lesnik thinks Westerners’ “yuck” reaction to bugs came with travel.

As early Europeans began traveling farther, they met other cultures. In 1493, a member of Christopher Columbus’ expedition to the Caribbean wrote about what he saw: “They eat all the snakes, the lizards, and spiders, and worms, that they find upon the ground; so that, to my fancy, their bestiality is greater than that of any beast upon the face of the earth.” In other words, he was comparing the people in the New World to animals.

Writings like this show that Europeans “considered the people they encountered beastlike because they ate insects,” Lesnik says. As Westerners colonized other cultures, they needed to make themselves feel superior to those cultures, she says. She suspects that this need strengthened Western disgust toward eating insects.

Disgust also can be learned by various messages shared within a culture, says Lesnik. We aren’t necessarily born thinking that insects are gross. “If a kid tries to put a bug in his mouth, many parents discourage that behavior and tell the kid it’s icky,” she observes.

Today, Europeans and North Americans aren’t the only ones who see eating insects as gross. The disgust is spreading to people in low-income nations who had been used to eating insects.

Arnold van Huis is a tropical entomologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. He noticed this shift in attitude while conducting a grasshopper study in the West African country of Niger. After adopting a Western lifestyle, “The people say, ‘We have a certain standard of living now, and we don’t eat insects anymore,’” van Huis reports. “They go for the hamburger instead of the nice grasshoppers.”

Changing minds

Can disgust be unlearned? For some people, education does the trick.

Six years ago, Robert Nathan Allen, a recent college graduate, was working as a bartender in Austin, Texas. At some point, his mom shared a video about edible insects. “She sent it as a joke — said it seemed like something wacky my dad and I would try,” Allen recalls. The video explained how bugs are good for us and good for the Earth, just as Sarah and her classmates had learned in school. “I thought this was just incredible,” Allen says.

He looked around for insect foods. He found the occasional bag of candied ants or chocolate-covered grasshoppers for sale. But there wasn’t much else available in the United States.

He started calling insect researchers on the phone. “I’ve got a bar in Austin and I want to serve bugs,” he would say. “What should I do?” Some people hung up. Others laughed him off the phone. But finally a professor confided that he cooks up a batch of bugs and brings them to school each year on the last day of class. “Everyone eats them. We all have a blast,” he said. “But please don’t tell anybody,” he implored of Allen, “because I don’t want the administration to make me stop.”

That phone call didn’t result in any new insect foods or recipes for Allen’s bar. But it did something bigger: It spurred Allen to action. “This professor was worried he’d be barred from serving a food that’s eaten by billions simply because it was stigmatized in our Western food culture,” Allen says. That made him realize there was “the need to educate the public and address the cultural taboo.”

Allen got in touch with researchers and business people who shared his goals. He discovered other campuses that host public insect-tasting events. Each year, some 30,000 people attend Purdue University’s Bug Bowl. And in February, Montana State University held its 30th annual Bug Buffet. This weeklong event features cook-off competitions, lectures and plenty of insect treats to sample.

In 2013, Allen founded an Austin nonprofit called Little Herds. The organization teaches the public about the benefits of edible insects, sometimes known as “mini livestock.”

Early on, the group set up tasting booths at local farmers’ markets. They gave talks at schools. They advertised at museums. Right away they realized their prime audience: children. Most parents wouldn’t dare reach for a roasted cricket before first sampling a nicer-looking food, such as a cookie made with cricket flour. But “little kids would just walk up and start chowing down on the crickets,” Allen says.

Fear of missing out — on bugs

Kids may be a somewhat easy sell when it comes to insects. That’s why some researchers have focused on adults. They’ve tried to figure out what traits make people likely to try insects. For a 2015 study, Rozin at the University of Pennsylvania and his colleagues gave 399 people from the United States or India an online survey about food. Participants saw pictures of cookies. Or breads baked with mealworm flour. And tacos or crepes containing whole grasshoppers. Then they asked the participants how willing they would be to sample those foods.

These researchers also asked the participants about their religion and politics. And they asked if participants agreed with statements such as: “eating bugs is disgusting,” “bugs are nutritious,” or “eating bugs puts you at risk for disease.” People also reported how willing they were to try new foods, how sensitive they were to disgust and how much they like risk and spontaneity.

Disgust was the most common reason people refuse to eat bugs, this study found. People who were most likely to try eating insects were those who weren’t easily grossed out, who didn’t mind unfamiliar foods and who liked new experiences (and telling others about them). Rozin’s team reported its findings, last year, in the Journal of Insects as Food and Feed.

Another team of researchers surveyed 368 meat eaters in Flanders, Belgium. According to their analysis, Westerners are most willing to replace meat with bugs if they’re young, male, open to new foods, environmentally conscious and already trying to eat less meat. Those 2014 findings were published in Food Quality and Preference.

Potential insect eaters may share another key trait: fear of missing out, often known as FOMO. In 2015, behavioral economists carried out a study to learn what types of messages might nudge people to try insects. At a shopping mall in England, the team lured shoppers to a table of dry-roasted crickets by posting three different signs. One described the health benefits of eating insects. A second tried to make eating insects seem normal. It showed a photo of family members at a restaurant and enjoying crickets. The third sign tapped into FOMO by showing a near-empty plate of roasted bugs with the plea, “Don’t miss your chance to try.”

The sign about health benefits did OK at attracting shoppers to the bug-foods table. The sign with the family photo did better. But the FOMO poster worked best.

It’s a marketer’s version of peer pressure. That tactic also seemed effective in the New Hampshire classroom. At the bug buffet, Sarah’s classmate Ruby Drake initially steered clear of insect foods. “I was just going to have the gummy worms,” she says. But after a friend begged her to try “one of the real bugs,” Drake picked up a roasted cricket.

The taste test ended quickly. “It crumbled the minute I touched it, and that grossed me out,” Drake says. “I spit it out.”

But that crunchy critter wasn’t a deal breaker. Drake also tried cricket-flour chips. “Those were pretty good,” she says. “I would put them in my lunch box.”

As for the dry-roasted crickets, Nihan says she would eat them again. However, she adds, “I’d probably brush my teeth afterward because the legs can get stuck in your teeth.”